Health

‘Written on Water’ Is a Guide for Surviving Historical past

It’s unnerving to know you might be residing in historical past. Previously decade, as phrases I’d first encountered in books erupted into my day by day lexicon—phrases like fascism, international pandemic, and ecological catastrophe—then settled, with alarming pace, into the static of how issues are, I’ve typically felt dizzy and unsure of the right way to reside. I’ve felt, as the author Eileen Chang as soon as wrote, like my on a regular basis life “is slightly out of order, out of order to a terrifying diploma.”

Generally I’ve consoled myself with what feels just like the exceptionalism of our current instability. Has the tempo of change—social, political, ecological, technological—ever moved with such hallucinatory, harmful depth? However this comfort doesn’t attain the extra pressing query: Whereas I’m being hurled into the scary future, what am I imagined to do about breakfast, and vacuuming, and laundry? After I really feel caught like this, between the tidal tug of the instances and the calls of my small however urgent life, studying a author like Chang is what brings me true consolation.

Zhang Ailing, also called Eileen Chang, grew to become a literary wunderkind in her native Shanghai for her fashionable and slyly observant tales of metropolis amorous affairs and romances—“among the trivial issues that occur between women and men,” as she put it, with attribute understatement—earlier than falling into obscurity after the 1949 Revolution, when she and her work have been not welcome in mainland China. She was later rediscovered by Taiwanese and Hong Kong readers.

The details of her historic period serve a wholesome dose of humility to my very own sense of latest tumult: As Chang was coming of age, competing warlords have been nonetheless trampling the grave of the Qing dynasty. China was combating the invading Japanese whereas additionally embroiled in a civil warfare. Mao’s Communist rebels have been marching steadily within the provinces, making ready to overturn all the things. Elsewhere, World Struggle II was raging. All of this historic noise sparkles within the background of Chang’s writing—and if you happen to look intently, informs its very core—however someway, her eye stays determinedly educated on the person human life, catching and analyzing these fluttering bits of actuality that the tides of historical past threaten to clean away. A brand new version of her early essays, Written on Water, translated by Andrew F. Jones (and edited by Jones and Nicole Huang), captures Chang’s irreverent voice and her cussed on a regular basis sensibility. This sensibility, powered by a modest humanism and fashioned by a delicate and heartbreaking self-discipline, has turn out to be my guide for surviving historical past.

In 1944, when Written on Water was first printed, Shanghai was a metropolis of commerce and vogue and unwilling political entanglement. China’s most cosmopolitan metropolis as a result of it was chopped up for overseas concessions after the primary Opium Struggle, Shanghai to today has a popularity for “imply” and savvy individuals who know “the right way to fish in troubled waters,” as Chang wrote. Like many Shanghainese, Chang herself was a “conventional Chinese language [person] tempered by the excessive stress of contemporary life,” one in all many “misshapen merchandise” of a spot the place so many ideologies, cultures, and tendencies met and clashed and melded.

Her life, too, was misshapen by the wild instability of her time. In “Whispers,” Chang divulges that her father, as soon as a popular aristocrat within the Qing dynasty court docket, was an opium addict who dominated dictatorially over his spouse, concubines, and kids. As soon as, he punished Chang by locking her in a room for months, refusing her medical remedy even when she bought dysentery; solely with the assistance of a servant did she escape that room, and that family, one “chilly bitter” evening. Her mom, a bourgeois lady who most well-liked all issues European, left Chang along with her father for years at a time whereas she traveled. Later, when Chang was a scholar on the College of Hong Kong, the arrival of Japanese bombers minimize her research brief, forcing her to return to Shanghai. She was solely in Hong Kong in any respect as a result of the world warfare had made college in London an impossibility.

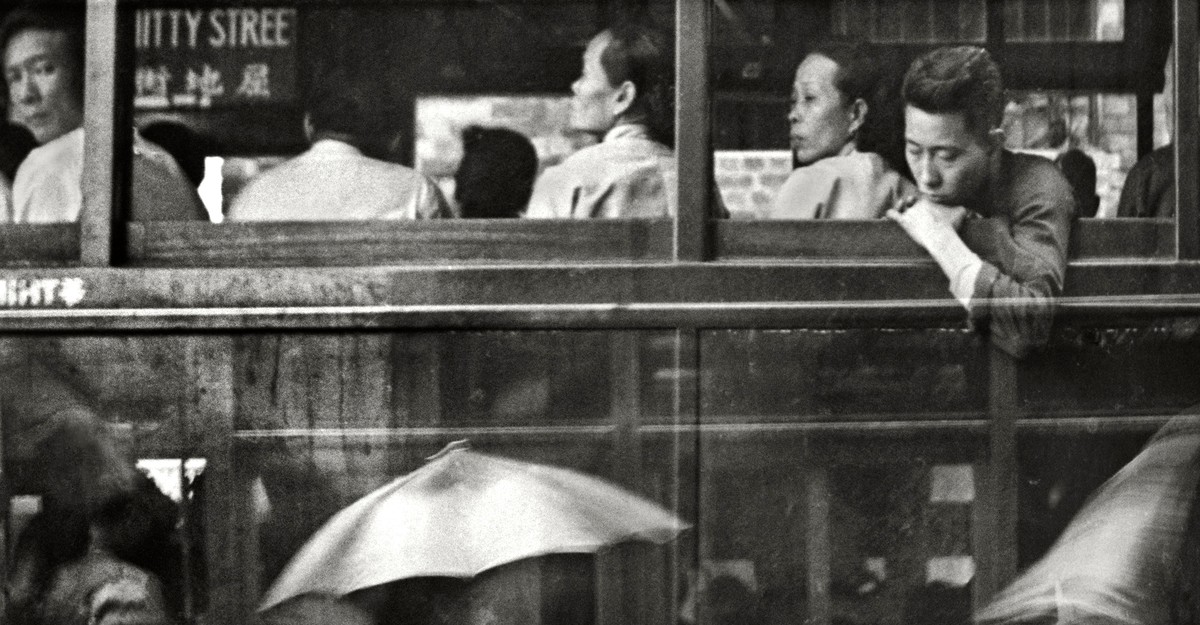

However what’s captured in these essays just isn’t Chang’s life a lot as her way of life and seeing. These are dashes of vivid statement, sketches of no matter Chang occurs to wish to write about: films, cash, her buddies’ favourite sayings. Take “On Carrots,” a two-paragraph transcription of a reminiscence her aunt as soon as recounted over a meal of turnip soup, about Granny feeding carrots to the pet cricket, which Chang thought a “fashionable little essay.” Or “Below an Umbrella,” a bite-size riff on a wet day that doubles as a parable about class. “Those that don’t have an umbrella press in opposition to those that do, squeezing beneath the perimeters of passing umbrellas to keep away from the rain,” she writes. “However the water cascading from the umbrellas seems to be worse than the rain itself and the individuals squeezed between umbrellas are soaked to the pores and skin.” Her crisp ethical? “When poor of us affiliate with the wealthy, they normally get soaked.”

Then there may be the structurally fascinating “Epilogue: Days and Nights of China,” which follows the author step-by-step on a stroll to the vegetable market. Chang describes in fastidious element the attention-grabbing individuals she passes on her manner, as if transcribing one of many full of life character drawings interspersed all through the e book (“a tangerine vendor,” “a Taoist monk,” “a servant lady”). Then she goes dwelling, writes a poem, and the essay—and the e book—ends.

Written on Water evokes a lyric Chinese language conception of ephemerality whereas additionally alluding to Keats (his headstone reads “Whose title was writ in water”). As Huang writes in an afterword, the title got here to Chang in English first. However for me, it could possibly’t seize the barbed playfulness of the Chinese language, 流言 (Liu Yan), which interprets to “flowing phrases” but additionally means “gossip.” Certainly, Chang relished any event to take a “stealthy look at each other’s non-public lives.” She declared, “The secrets and techniques of on a regular basis life should be made public at the very least yearly.” She thought literature ought to “plainly sing in reward of the placid.” She most well-liked the “noise and clatter” of metropolis streets to “rousing” symphonies. She wished historians would write extra about “irrelevant minutiae.”

With this assertion, she opens “From the Ashes,” her account of the Battle of Hong Kong, Japan’s December 1941 assault on the then–British colony. Within the essay, Chang recollects surviving weeks of shelling and unhappily volunteering as a makeshift nurse. However what she foregrounds is a string of virtually devastatingly flippant observations: the “rich abroad Chinese language” dorm mate who’d packed garments for dances and dinner events however didn’t know what to put on for a warfare; “hardy” Evelyn who stuffed herself with extra rice than ever whereas rations ran out, after which bought constipated; defiant Yanying—“the one one in all my classmates who had any guts”—who left the basement to take a shower, singing whilst a stray bullet shattered the window. These anecdotes are instructed with amusement and a few light mocking, but additionally with admiration: Listed here are individuals who, in a literal warfare zone, insisted on the small pleasures of residing.

Chang defended her trivial tales in opposition to those that may want them extra heroic. Unusual individuals going about their lives, falling in love, and appearing on petty fancies may not make a “monument to an period,” however, she wrote, “persons are extra easy and unguarded in love than they’re in warfare or revolution.” Chang had no need to write down about “supermen,” who “are born of particular epochs.” Why, when the “everlasting”—the grist of day by day life that’s the solely true stability—was proper there? She understood the contradiction in her perception: that though on a regular basis life is essentially “precarious,” “topic at common intervals to destruction,” it is usually the fabric from which springs the actually human, and the divine. (Additionally: “Chest-pounding, wildly gesticulating heroes are annoying.”)

Learn: Nice intercourse within the time of warfare

I learn in Chang’s decided apolitical gaze a transgressive, female ethos. For a substantial amount of historical past—and nonetheless, amazingly, at present—males have formed epochs, with their empires and conquests. In the meantime, ladies have sustained the fact that’s accrued in days: going to the market, mending clothes, cooking and cleansing, carrying and caring for the people who find themselves coming subsequent. In “A Chronicle of Altering Garments,” Chang paperwork the passing vogue fads—collars rising then disappearing, necklines going from sq. to spherical to heart-shaped—as “warlords got here and went.” Chang liked garments and designed a lot of her personal. Vogue is decidedly trivial, and Chang’s curiosity in it’s a highly effective facet of her “misshapen” morality, a method of insisting on one thing minorly significant in a world of continually shifting values. Buffeted from place to put by warfare, Chang might management little of her exterior circumstances, however she might resolve, day-after-day, what to put on.

“Every of us lives inside our personal garments,” she writes. We reside inside our garments; we reside inside our days. Imagined as a container for all times itself, the vanities of vogue acquire pressing ethical significance. On this gentle, the dullness of menswear may be seen as a type of depravity: “If males have been extra inquisitive about clothes,” Chang writes, they is likely to be “a bit much less inclined to make use of varied schemes and stratagems to draw the eye and admiration of society and sacrifice the well-being of the nation and the individuals within the strategy of securing their very own status.” Consider the uniforms of males like Steve Jobs or Mao Zedong, who most well-liked to protect the vitality it took to decorate for engaging in what Chang referred to as “earth-shattering deeds.” Chang was already well-known when she printed this e book, however she distances her writing from this epic realm, evaluating herself as a substitute to a toddler operating dwelling from college, wanting to gab about all the things she’s seen to any accessible grownup.

Can seeing be an ethic, a manner we select to reside? For Chang, it was additionally a approach to proceed residing. To repair a gaze can also be to search out one thing—something—to carry on to amid terror and chaos. In “Seeing With the Streets,” Chang teaches us the right way to see the fact that may be irrevocably disrupted by historical past. She walks by town, observing the shows of store home windows, passing by the smoke and smells of avenue distributors, and noticing the same old individuals and issues, earlier than a army blockade brings her stroll and day to a halt. On a regular basis life is everlasting; in warfare, the everlasting is in grave hazard.

Behind Chang’s realizing irony, I hear a determined urgency. I hear the rapt consideration of somebody who loves her world and sees that it’s disappearing. I hear: What you treasure, nevertheless foolish, may not be right here tomorrow. Chang wrote just like the satan was chasing her. It’s as if she knew that when the period she lived in reached its fruits, there may not be a spot for somebody like her—a author between nations, epochs, and ideologies—“within the barren wastes of the long run.” “Hurry! Hurry!” she wrote. Hurry to seize actuality, as intently as doable; hurry, maintain on to it and preserve it. Then you definitely may need it for tomorrow, to show over in your hand, for just a bit pleasure, slightly amusement, slightly snicker, even after it’s not actual.

Whenever you purchase a e book utilizing a hyperlink on this web page, we obtain a fee. Thanks for supporting The Atlantic.

Related Posts

- Who Has the Finest Legs in Bodybuilding Historical past?

There have been a whole lot of discussions about who has the most effective bodyparts…

- Evil Eye Which means: Historical past & Symbolism + Plus How To Use It

The idea of the evil eye is hundreds of years outdated, and is predicated on…

- Sixth-fastest marathoner in historical past faces 10-year doping ban

One other Kenyan doping scandal has rocked the marathon world. On Monday, the Athletics Integrity…