Health Care

‘Working Class’ Does Not Equal ‘White’

That the phrases working class are synonymous within the minds of many Individuals with white working class is the results of a political fantasy. Because the award-winning historian Blair LM Kelley explains in her new e book, Black Folks: The Roots of the Black Working Class, Black individuals are extra prone to be working-class than white individuals are.

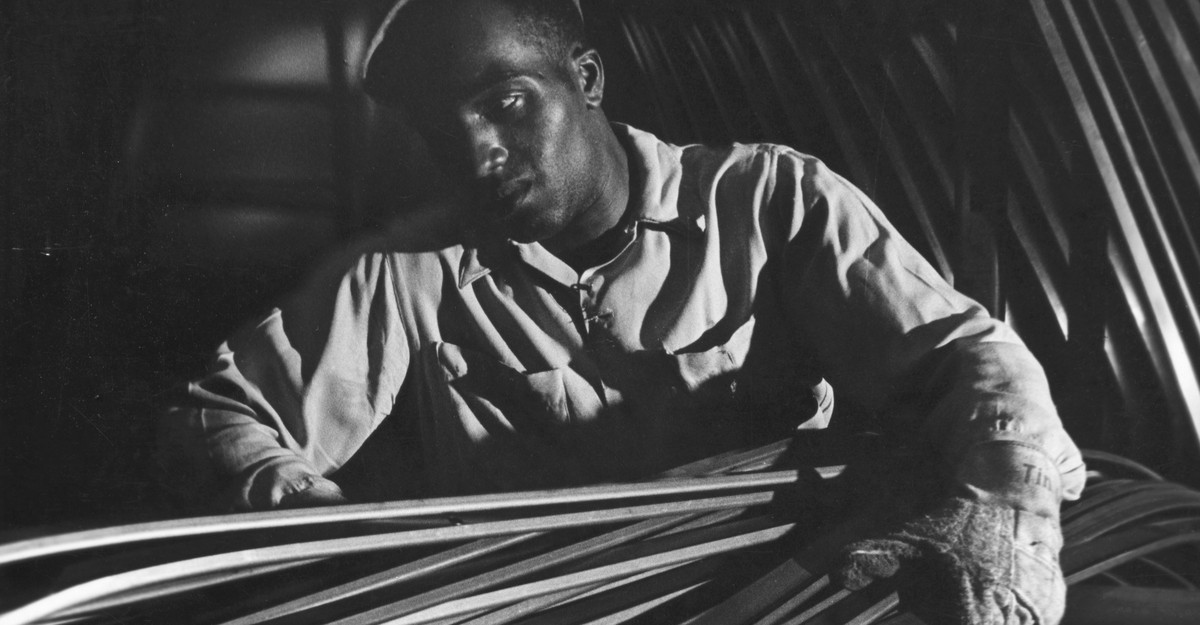

Kelley’s Black Folks opens our minds as much as Black employees, narrating their advanced lives over 200 years of American historical past. Kelley seems to be on the historical past of her personal working-class ancestors, in addition to the laundresses, Pullman porters, home maids, and postal employees who made up the world of Black labor. Their joys. Their expertise. Their challenges. She additionally provides historic context for the racist concepts about Black employees that endure in our time, whereas highlighting the ways in which Black labor organizing has all the time helped to battle again in opposition to bigotry.

Myths about race and sophistication proceed to dominate our political discourse. For a begin, it’s a fantasy that Individuals with out faculty levels are, by definition, “working class.” Amassed or inherited wealth is a extra correct indicator of sophistication standing than schooling (or wage), notably amid an unlimited racial wealth hole in the US. Wealth ranges of Black households whose members have a school diploma are much like these of white households whose members don’t have a high-school diploma. And people white high-school dropouts have larger homeownership charges than Black faculty graduates. Even when we had been measuring working-class standing by college-degree attainment, white Individuals (50.2 %) are far and away extra seemingly than Black Individuals (34.2 %), Latino Individuals (27.8 %), and Native Individuals (25.4 %) to have a school diploma, and subsequently not be working class by this insufficient measure.

Additionally it is a fantasy that “the white working class is synonymous with supporters of Donald Trump,” as Kelley factors out in Black Folks. The truth is, Trump’s base stays way more prosperous than is popularly portrayed. “It’s not essentially a query of [Trump voters] needing to be educated,” Kelley informed me once we spoke lately. “It’s a set of decisions that individuals are making about their place on this planet, and what makes them really feel verified and validated.”

All of those myths comprise our “nationwide mythos,” which “leaves little room for Black employees,” writes Kelley, the incoming director of the Heart for the Research of the American South on the College of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. We mentioned what classes we are able to glean from their historical past, from their on a regular basis lives, from their political organizing. Our dialog started with the Black folks we all know greatest: our households.

This interview has been condensed and edited for readability.

Ibram X. Kendi: Black Folks opens by chronicling the life story of your maternal grandfather, who was dealing with and preventing racism within the city of Canon, in northeast Georgia. What was placing for me was that my maternal grandfather, Alvin, is from Guyton, which can also be in jap Georgia, although nearer to Savannah. He handled racism there as nicely, fled to New York Metropolis. Your maternal grandfather made his option to North Carolina. Such similarities. Why did you resolve to start out the e book there?

Blair LM Kelley: It’s such a formative story for my household. It’s one my mom repeated many, many instances. I feel my mom actually wished me to know the diploma to which slavery had ended however the circumstances of subjugation had not. She wished me to get how shut that was to my lived expertise, that it wasn’t this far-off, distant factor that was lengthy gone.

Tying my household to this bigger historical past, I do know that’s a narrative so many individuals have of being compelled to flee. I actually wished to start with that as a result of I knew how common it was.

Kendi: You particularly wished Black Folks to “seize the character of the lives of Black employees, seeing them not simply as laborers, or members of a category, or activists, however as folks whose every day experiences mattered.” Why was capturing the character of their full lives so essential?

Kelley: I’ve by no means actually considered myself as a labor historian. Labor historical past had such a give attention to establishments and unions, and infighting between organizations. These had been fascinating, and issues you could know. However they weren’t the ways in which I knew my of us. My of us had been employees, however their lives, their complete lives, affected the way in which that they considered that work. And I hadn’t seen as a lot labor historical past that was targeted on what the entire being was like. Not only a factory-floor model of historical past, however somewhat a church, a home, a mother-daughter relationship. These sorts of issues I wished to see amplified, as a result of I feel they’re simply as significant for employees’ lives—if no more so—than the atomized workspace.

Learn: Booker T. Washington within the Atlantic on labor unions and civil rights

Kendi: You begin by writing a few blacksmith who was born in slavery—after which transfer on to different jobs, like washerwomen, train-car porters, home maids, and postal employees. Why particularly these occupations? Are there any particular occupations right now that Black working folks occupy that we may doubtlessly see as archetypal, or much like a few of these historic jobs?

Kelley: I feel that home employees are actually nonetheless an unimaginable inhabitants to consider. Their organizing is de facto unimaginable, and one thing I need to maintain enthusiastic about in my future work. I’m very a lot concerned about following postal employees now. I feel particularly throughout the COVID pandemic, we may see that there’s an actual battle being waged round postal work that I feel deserves continued consideration. The pandemic, once more, made us take into consideration Black folks in medical care, notably licensed nursing assistants. The ranks of those nurses are enormously stuffed by Black ladies, and so they bore the brunt of the pandemic. The gig economic system can also be actually fascinating to me. Black individuals are overrepresented in that house as nicely.

Kendi: You write that when Black employees are talked about in any respect, the very thought of labor is dropped completely. And as a substitute they’re described as “the poor,” and sometimes implied to be unworthy and unproductive. That is an echo of the characterization of enslaved Black folks as lazy and unmotivated. And also you wrote this within the opening pages of the e book to essentially set the stage for a bigger argument. What was that bigger argument?

Kelley: It’s that I feel there’s an unimaginable mislogic across the Black working class, one born in slavery. I put a quote from Thomas Jefferson about him observing Black folks and writing in Notes on the State of Virginia that they sleep loads. And I’m like, Sir, as you sit in your chair, and any person followers you and brings you your meals, who’re you calling lazy? And in order that stereotype and its afterlife in our modern considering is a confounding one to me. It’s one I actually wished to confront and unpack and pull the thread of all through the textual content. As a result of Black employees’ contributions to this nation are huge. So calling Black folks “lazy” or “the poor” misunderstands what we’ve completed and the way we consider ourselves.

Kendi: You additionally level out that there’s a misunderstanding that Black employees are unskilled. Particularly in writing about laundresses, you wrote in regards to the immense talent required. Is the concept of those Black employees as unskilled related to the concept of them as unmotivated and lazy—an extension of that?

Kelley: Sure. I used to be fascinated by the skilled-labor/unskilled-labor dynamic that students had used for understanding work. It actually struck me throughout the pandemic. The United Farm Employees had been exhibiting movies of farmworkers bundling radishes or choosing cauliflower, harvesting asparagus and transferring with such velocity that you may barely see how they did it. They usually’re classed as unskilled employees. Nonetheless right now, that’s how we might describe them. And so, for me, studying the accounts of choosing cotton, or washing laundry, or engaged on a Pullman automobile—all of these issues took data and examine and talent. I simply wished to explode that scholarly assumption about what’s expert and what’s unskilled.

Kendi: A lot of these Black individuals who had been referred to as unskilled previously—and even right now—labored in service-related occupations. I point out that as a result of there’s the racist concept that Black individuals are by nature servile, which undercuts the concept they’re truly extremely expert in doing these jobs. Do you see that too?

Kelley: Sure. I feel once you have a look at folks just like the Pullman porters, lots of whom had been extremely educated—they had been most well-liked if that they had some schooling. As a result of having the ability to have conversations, to anticipate what folks want—they actually had been the primary type of a concierge on these prepare automobiles—it actually necessitated super data and talent for what may appear like only a job serving. It’s a reminder of the dexterity of thoughts that many individuals carry to issues that we consider as service.

And the methods by which they may serve each other, and use their platform to check higher rights for all employees, it’s actually unimaginable. So usually we consider unions as egocentric. That’s a part of the damaging narrative that we now have of unions. That they’re taking charges from the employees, and so they don’t do a lot and so they don’t actually assist out. However once we have a look at a union just like the Brotherhood of Sleeping Automotive Porters, we see that they began the whole nation in increasing our idea of citizenship and civil rights.

Kendi: Certainly, A. Phillip Randolph, the founding father of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Automotive Porters, was the particular person behind the March on Washington in 1963, the place Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. gave his “I Have a Dream” speech. These automobile porters strove to advance themselves. However you write about how when Black employees are in a position to begin making extra money, or proudly owning land, and even begin companies, they usually averted “outward indications of success.” Racists imagined them to be uppity and even forgetting their place. However what about Black elites? What did they give thought to the Black working class, then and now?

Kelley: In the event you look again at Black newspapers within the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, you’ll discover them admonishing employees, “Don’t exit and spend your cash on these specific sorts of issues. Be very frugal. Don’t go to the faucet rooms and purchase all these fancy garments to put on on Sundays.” So there are parallels with the present Black elite. That’s an previous trope Black communities have been bouncing round for a extremely very long time: that in some way it can save you your approach out of the circumstances that make working-class life way more troublesome.

The house for pleasure, and the house for enjoyment and pleasure in the way you look and what you might have, and the methods by which working folks have spent cash have all the time been criticized. “I don’t appear like what my job is; I appear like who I need to appear like”—that sort of pleasure is historically a Black working-class factor. Though it seems to be very totally different right now when sporting a Gucci belt or one thing.

Learn: Is organized labor making a comeback?

Kendi: Members of the Black working class haven’t solely carved out areas for pleasure and delight and pleasure. They’ve carved out areas for politics, for organizing, for unions. You discuss how members of the Black working class usually tend to be union members right now than every other racial group. Primarily based in your analysis, why do you suppose that’s taking place? Which is to ask, why do you suppose Black individuals are on the forefront of this growth of union organizing and activism in our time?

Kelley: I feel Black employees have a unique outlook on the narratives round unionizing, and what worth unions might need. Black employees are already in a important stance to say, “Properly, no, let me consider this for myself. And no, truly I feel a union would assist!” Coming collectively is a option to assist us and elevate us. It suits the narrative of the broader lives we now have lived in our households and communities. Unions simply resonate with how Black communities have fought over time, which is why we see Black of us forming unions from the very first moments of freedom, all the way in which until proper now.

Kendi: You even described enslaved Black of us operating away as partaking in nascent labor strikes.

Kelley: Completely. They understood what a distinction their labor made. So usually we neglect that people who find themselves subjugated have mental lives.

Kendi: Positively. That brings me to 2 quotes out of your e book that I wished you to replicate on. The primary touches on what we had been simply speaking about—how Minnie Savage, a baby of exploited and constrained sharecroppers, knew the worth of her crop-picking in Accomack County, Virginia. At 16 years previous, she fled. You write, “Minne dreamed of dwelling in a spot the place it didn’t really feel like they had been slaves anymore. A spot the place she might be paid pretty for her arduous work. A spot the place she may safely be part of with others to demand truthful remedy. She needed to depart Accomack to ‘get free of freedom.’”

Kelley: I like Minnie as a determine, and discovering her interview was such a present. She occurred to be from the place the place my grandfather was from. And it was so fascinating to comply with her as she made her option to Philadelphia. Simply keep in mind that, for thus many, migration was this massive dream of chance and the imaginative and prescient of one thing new and one thing broader and one thing stronger. And chronicling her disappointment in what occurred within the first many years after she migrates, after which additionally chronicling that she does find yourself with one thing a lot stronger, and one thing she’s actually happy with—she was an incredible determine to put in writing about.

Kendi: And at last: “The Trump-caused obsession with the white working class … has obscured the truth that essentially the most lively, most engaged, most knowledgeable, and most impassioned working class in America is the Black working class.”

Kelley: I’m a scholar of Black folks, and I like Black folks. I feel we be taught a lot once we shift our gaze, once we suppose in a different way, once we take note of different folks and glean from their historical past. Black life has a lot to show all of us about what is feasible.

Whenever you purchase a e book utilizing a hyperlink on this web page, we obtain a fee. Thanks for supporting The Atlantic.

Related Posts

- Revolutionizing Hair Take care of Black Girls – Hype Hair

Meet Deangelo Glenn, the visionary celeb hairstylist who's making waves on the planet of hair…

- ‘The Different Black Lady’ and the Haunting of Black Hair

Within the 1989 surrealist satire Chameleon Avenue, two Black males bicker after one says that…

- Convention Focuses on ‘Reclaiming Black Wealth’

What You Must Know The monetary companies business’s largest gathering of Black leaders is in…