Health Care

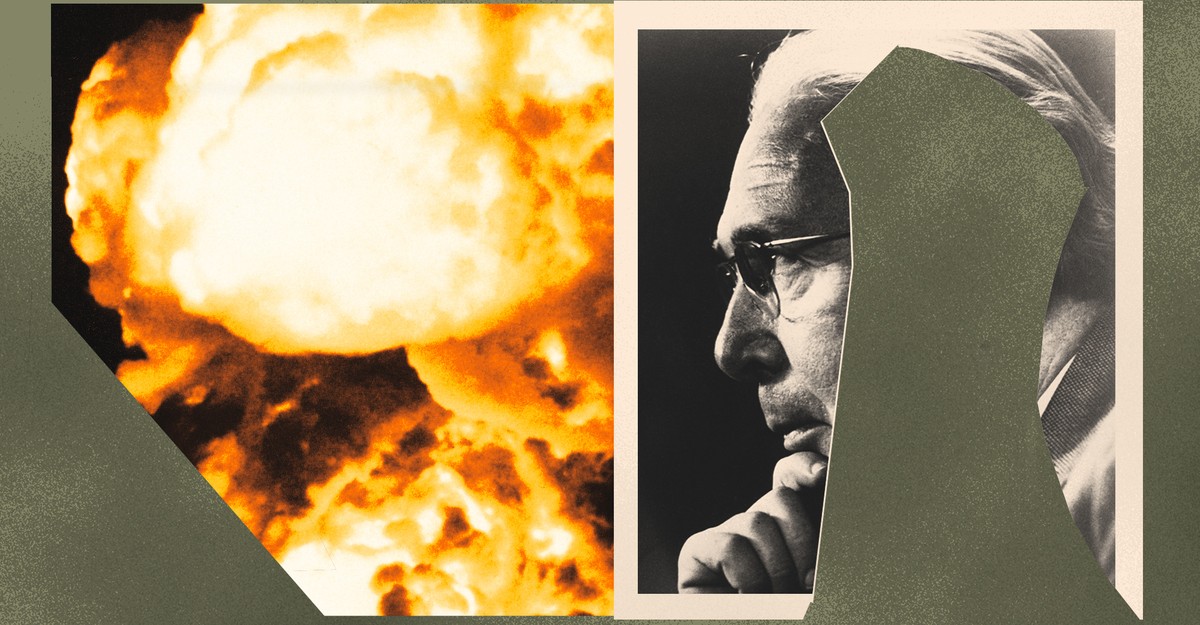

What AI Scientists Can Be taught From Nuclear Scientists

J. Robert Oppenheimer, the daddy of the atomic bomb, spent years wrestling with the battle between his science and the dictates of his conscience. Partially as a result of he publicly expressed his issues in regards to the hydrogen bomb and a nuclear arms race, Oppenheimer—the topic of a brand new biopic—ended his profession as a martyr in Chilly Struggle politics. Fortuitously, many different early nuclear specialists, together with the College of Chicago scientists who first produced a series response, felt an obligation to assist stop the misuse of atomic science. These scientists understood one thing that at the moment’s pioneers in synthetic intelligence and genetic engineering additionally want to acknowledge: The individuals who usher revolutionary advances into the world have each the experience and the ethical duty to assist society deal with their risks.

In laboratories at universities and at for-profit corporations at the moment, researchers are engaged on applied sciences that increase profound moral questions. Can we engineer crops and animals immune to pure predators with out upsetting the steadiness of nature? Ought to we enable patents on life kinds? Can we ethically repair supposed abnormalities in human beings? Ought to we enable machines to make consequential choices—as an example, whether or not to make use of drive to reply to a risk, or whether or not to launch a retaliatory nuclear strike? Atomic scientists at Chicago and elsewhere left behind a mannequin for the accountable conduct of science, a mannequin as relevant now because it was in Oppenheimer’s day.

Learn: The true lesson from The Making of the Atomic Bomb

The race to the atom bomb started on the Metallurgical Laboratory on the College of Chicago, the place, on December 2, 1942, the primary engineered, self-sustaining nuclear-fission response occurred. The scientists gathered in what had turn out to be often known as an “atomic village” included Leo Szilard, a Hungarian-born physicist who a couple of years earlier had helped persuade Albert Einstein to warn President Franklin D. Roosevelt {that a} weapon of superior energy was inside scientific attain—and that Hitler’s scientists knew it too. The now-famous Einstein-Szilard letter, which launched america on the crash course often known as the Manhattan Undertaking, was the nuclear age’s first nice act of scientific duty. The primary lesson from the Met Lab was: Scientific data, as soon as obtained, can’t be referred to as again. Perceiving the world-changing potential of current discoveries in nuclear physics, Szilard and his colleagues needed to inform the leaders of our democracy.

Chicago’s atomic village had an eclectic mixture of scientists. Some, such because the physicist John Simpson, have been younger Individuals who had grown up amid New Deal social reforms. Among the many extra established scientists have been a lot of Jewish émigrés, together with Szilard, the German physicist James Franck, and the Russian German biophysicist Eugene Rabinowitch, whose experiences earlier than leaving Europe had sensitized them in numerous methods to the ethical dimensions of science. Franck, in reality, had firsthand expertise of the subjection of science to politics. Whereas working as a younger researcher in Germany when World Struggle I started, he had volunteered for the kaiser’s military and was an officer within the unit that launched chlorine gasoline onto the battlefield. His good friend Niels Bohr, the distinguished Danish physicist and Nobel laureate, harshly criticized his resolution to simply accept the function, which Franck got here to remorse deeply.

By 1943, the first work on nuclear-bomb improvement had shifted to Oak Ridge, Tennessee; Hanford, Washington; and Los Alamos, New Mexico. The scientists remaining at Chicago’s Met Lab had time to attempt to form choices about the usage of nuclear expertise, each in what remained of World Struggle II and within the looming postwar interval. The second lesson from the Met Lab was that, though scientific discovery is irreversible, its results could be regulated. In her 1965 e book, A Peril and a Hope: The Scientists’ Motion in America, 1945–1947, the historian Alice Kimball Smith, drawing on archival materials and interviews, chronicled the extreme discussions raging among the many scientists throughout this era. The Met Lab scientists in the end arrived at particular aims that have been lofty, sensible, or each. They needed to provide Japan a preview of the atomic bomb’s energy and the chance to give up earlier than being subjected to it. Additionally they needed to free science from the fetters of official secrecy, avert an arms race, and design worldwide establishments to manipulate nuclear expertise.

The third lesson from the Met Lab was that main choices in regards to the utility of latest expertise ought to be made by civilians in a clear democratic course of. Within the mid-’40s, the Chicago atomic scientists started bringing their issues to leaders of the Manhattan Undertaking after which to public officers. The Military forms most popular to maintain secrets and techniques, however the scientists fought it each step of the best way. Szilard, Franck, Rabinowitch, Simpson, and scores of their colleagues led the trouble to coach politicians and inform the general public about nuclear risks. The scientists organized associations, among the many first of which was the Atomic Scientists of Chicago. They gave lectures, wrote opinion essays, and based publications, most notably the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, which Met Lab scientists edited and printed on the College of Chicago campus. Working with colleagues on the different Manhattan Undertaking websites, they marshaled help for the passage of the Atomic Vitality Act, which created an unbiased company of civilians, accountable to the president and Congress, to supervise the event and deployment of nuclear science. Their efforts continued effectively into the Chilly Struggle, with the profitable campaigns for nuclear check bans, nonproliferation compacts, and arms-control agreements.

Within the twenty first century, many choices in regards to the improvement and deployment of latest applied sciences are happening in personal laboratories and company government suites, out of the general public’s sight. Just like the navy’s secrecy necessities so resented by the Met Lab scientists, unique personal possession of scientific concepts impedes collaboration and the free stream of information upon which the progress of science relies upon. The primacy of personal resolution making is an abrogation of the general public’s proper to take part, via the democratic course of, in moral choices in regards to the utility of scientific and technical data. These are the form of selections the Met Lab scientists thought-about to be the general public’s to make.

From the July 1995 challenge: Was It Proper?

In August 1945, two atomic bombs brought about the rapid or eventual deaths of 150,000 to 220,000 individuals in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Some months later, at a gathering within the White Home, Oppenheimer instructed Harry Truman, “Mr. President, I’ve blood on my palms.” However Truman reminded the physicist that the choice to drop the bombs was his personal. Having made the weapon attainable, the nation’s atomic scientists however acquitted themselves effectively. The regime they fostered, the template they created for accountable science, helped make that first use of nuclear weapons the one use in struggle up to now. We might be smart to heed the teachings they realized.

Related Posts

- Scientists suppose AI can pace up their discoveries : Photographs

AI just like the type used to make pictures is now getting used to design…

- AI Order for Health Care May Bring Patients, Doctors Closer

You might have used ChatGPT-4 or one of many different new synthetic intelligence chatbots to…

- Heard at HLTH: Healthcare Execs Share Views on AI, Digital Well being and Worth-based Care

On the HLTH 2023 occasion earlier this month, executives from a number of the largest…