Health Care

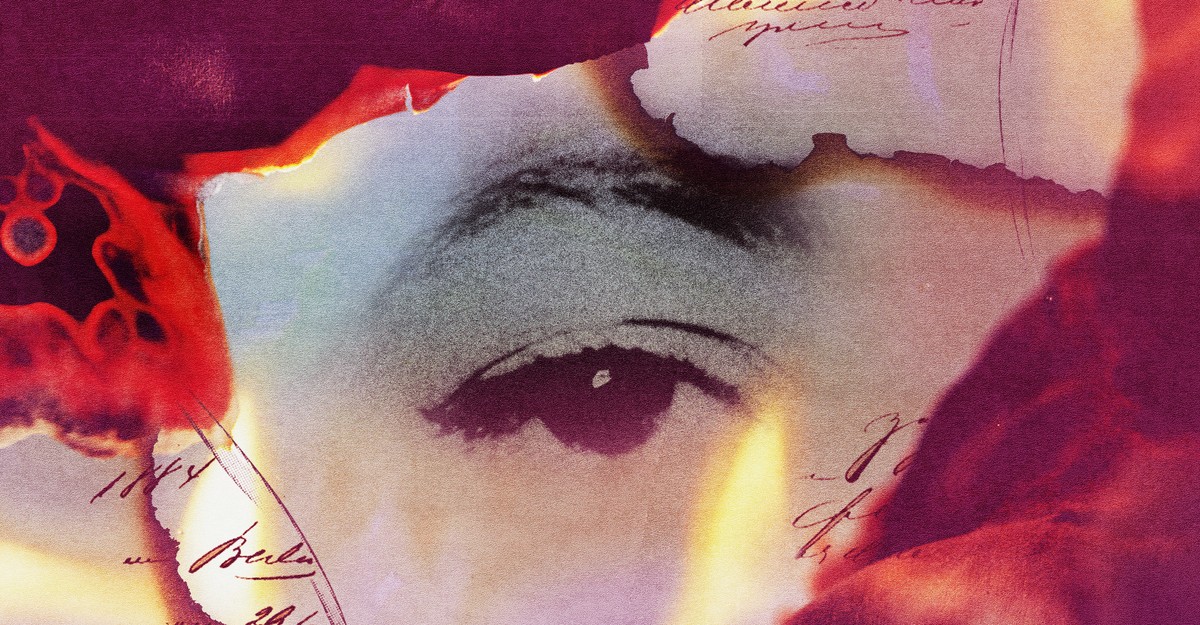

The Girls Writers Who Destroyed Their Personal Work

How the French writers Marguerite Duras and Barbara Molinard first met is unclear, however their friendship was considered one of such mutual admiration that it now appears a fated union. Totally different although their lives had been, the 2 girls shared an essential attribute: Of their fiction, they each provided intimate depictions of the misogyny they suffered. This was uncommon, even stunning, for girls writers on the time.

By the mid-Nineteen Sixties, Duras was a prolific author and an acclaimed filmmaker throughout the French mental class. Nobody knew Molinard. In her 40s, she started to put in writing brief fiction and did so with an uncommon fervor, generally working for weeks with out pause. To today, little is understood about Molinard exactly as a result of she didn’t want to be identified. She went to nice pains to make sure this, destroying almost each web page she wrote.

“Every little thing Barbara Molinard has written has been torn to shreds,” Duras introduced within the preface to Panics, Molinard’s assortment of grotesque and bleakly antic tales, first printed in France in 1969 and launched final 12 months within the U.S. in an excellent translation by Emma Ramadan. Duras was not being hyperbolic; upon finishing a narrative, Molinard would tear every web page into items, which she piled onto her desk and ultimately pitched into a hearth. Then she rewrote them: “They had been put again collectively, torn up once more, put again collectively once more,” Duras wrote. Solely the tales in Panics, which had been rescued by Duras and by Molinard’s husband, had been spared.

Learn: What a well-known author’s early work can train us about failure

Molinard is much from the one author to destroy her work. In July 1962, following Ted Hughes’s infidelity and the collapse of their marriage, the American poet Sylvia Plath could have set fireplace to letters she exchanged together with her mom, or her in-progress novel, or a few of her husband’s poems. Paul Alexander, in his biography of Plath, Tough Magic, interpreted this as a “bonfire” set in a “match of rage.” In Sylvia Plath: Technique and Insanity, Edward Butscher attributes the act to the “bitch goddess” Plath had turn into. Seven months later, Plath took her personal life.

She couldn’t probably have identified that her blunted life would encourage a area of literary scholarship, documentaries and have movies, and subsequent generations of writers and poets. However she actually understood how little management she had over the best way she was perceived, a miserable reality most ladies study to simply accept of their youth. In her e book The Silent Lady, a research of biographies of Plath, Janet Malcolm writes, “In any battle between the general public’s inviolable proper to be diverted and a person’s want to be left alone, the general public virtually at all times prevails.” By the summer time of 1962, Plath could have felt that the general public had already received. Fireplace would have been consoling, its devastation totalizing.

Maybe Plath wished to hide the private particulars she had divulged in her letters or in her novel; we can not know for certain. What may be sifted from the ashes is {that a} author’s causes for destroying her personal work are complicated. The act isn’t the results of a fevered impulse, foolish rage—at the very least, not solely this stuff. Moderately, it may be intentional and calculated, a show of ferocious will, an suave last flourish.

Learn: The haunting final letters of Sylvia Plath

In December 1977, the English novelist and poet Rosemary Tonks endured surgical procedure to restore indifferent retinas in each of her eyes. She was partially blind for just a few years after the process and went to stay within the seaside city of Bournemouth, to convalesce and to flee the disarray of her life in London, the place she’d earned a popularity as a champagne-glugging bohemian. Tonks by no means returned to that way of life; as a substitute, she retreated so totally that the BBC titled its 2009 radio characteristic about her life The Poet Who Vanished.

It’s considerably troublesome to sq. the latter a part of Tonks’s life with the fizzy and carefree characters who populate her novels. Min, the narrator of Tonks’s novel The Bloater, first printed in 1968 and reissued final 12 months, appears the sort of younger girl Tonks might need as soon as been. She is chatty, self-absorbed, and delightfully frivolous, at all times swilling a drink and in search of one other pour. Her husband is a horrible bore, so she entertains a handful of intriguing suitors.

For Tonks, the dazzle of that sort of life had dulled by center age. The last decade earlier than her eye surgical procedure was turbulent, starting together with her mom’s sudden loss of life, in 1968. Tonks additionally had neuritis in her left hand, which made writing exceedingly troublesome as a result of her proper hand was already broken by childhood polio. Her marriage fell aside. Trying to find solace, she turned to the religious realm and ultimately discovered Christianity. She learn the New Testomony as her sight returned, and traveled to Jerusalem in 1981 to be baptized. Christianity provided her the possibility to shed her disappointing previous and begin anew.

Tonks’s astonishing reinvention may very well be learn as the results of a midlife disaster, or a psychological break, or the ecstatic embrace of spiritual redemption. However every of those twists her story into one thing acquainted and foregone, rendering the alternatives she made determined and piteous. Quite the opposite, Tonks’s retreat appears to have introduced her the peace that eluded her at earlier levels of her life, and allowed her to extra totally reject the English society for which she had at all times felt some combination of captivation and revulsion. In her 1967 poem “Dependancy to an Previous Mattress,” she wrote:

In the meantime … I stay on … highly effective, disobedient,

Inside their draughty haberdasher’s local weather,

With these folks … who’re going to obsess me,

Potatoes, dentists, folks I hardly know, it’s unforgivable

For this isn’t my life

However theirs, that I’m residing.

And I wolf, bolt, gulp it down, day after day.

After leaving London, Tonks allegedly checked out her personal books from libraries with the intention to destroy them. She refused requests to reissue her work, which by then included two collections of poetry and 6 novels. She even incinerated an unpublished manuscript. Tonks allowed herself just one e book, the Bible, which she referred to as her “full handbook” for learn how to stay. She was identified to face on road corners handing out copies to passersby.

In accordance with a Nationwide Bureau of Financial Analysis working paper, by 1970, girls nonetheless printed solely a 3rd of the variety of books males printed every year within the U.S. Globally, too, Tonks and Molinard and Plath, who started publishing in the course of the twentieth century, had been among the many first generations of ladies writers who weren’t considered primarily as exceptions to their gender—the best way the Brontë sisters, Jane Austen, and Mary Shelley had been regarded. {That a} girl is perhaps celebrated for her literary efforts, earn recognition and prizes, and luxuriate in a large readership had been comparatively current developments.

Learn: The hazards of writing whereas feminine

For some girls, this new consideration introduced surprising scrutiny, in addition to the grim realization that their legacy could be dictated by anybody however themselves. As Janet Malcom wrote, “To [her] readers … Plath will at all times be younger and in a rage over Hughes’s unfaithfulness.”

Tonks roundly rejected the concept that a author whose work is publicly consumed ought to be obligated to take care of the general public. In 1963, greater than a decade earlier than her retreat, she informed Peter Orr of the British Council, in an interview, “I believe it’s diabolical, this getting of a poet out of his or her again room and the making of them into public figures who’ve to present opinions each twenty seconds.”

The American creator Ann Petry shared Tonks’s stance. Movie star got here to her all of the sudden following the publication of her first novel, The Road, which follows an ensemble of impoverished characters residing in Harlem and ignored by a metropolis disinvested in its Black inhabitants. Revealed in 1946, it was the primary novel by a Black girl to promote greater than 1 million copies; the ensuing sensation thrust Petry right into a highlight she’d by no means wished. Misunderstood by white critics, who construed her important expertise as an anomaly and in contrast her work towards that of just a few different Black writers, she wrote in her journal that she felt overexposed, like “a helpless creature impaled on a dissecting desk—for public viewing.”

In 1969, Petry agreed to ship 19 packing containers’ price of her private papers to Boston College. She regretted it virtually instantly. By the early Nineteen Eighties, she confessed in her journal that she was distrustful of and baffled by the curiosity different folks took in her personal supplies: “It by no means occurred to me that in my lifetime folks could be poking via that stuff … Why not? Principally as a result of I attempted to vanish.”

In her memoir, At Dwelling Inside: A Daughter’s Tribute to Ann Petry, Petry’s daughter, Elisabeth, recollects that her mom spent the final years of her life on a “shred-and-burn marketing campaign.” In the summertime of 1983, Petry wrote, “Destroy them, journal by journal, or else edit them. No. Destroy them.” She redacted entire passages of her journals and generally changed them with new writing. In interviews, she provided inconsistent dates for her delivery, refused to reveal the date of her marriage, and was identified to brighten tales from her childhood. Although these obfuscations may very well be considered as self-serving editorialization, Petry didn’t appear fascinated about authoring her personal mythology, or permitting anybody else to take action. She rejected would-be biographers in addition to most requests for interviews.

Petry’s suspicion of what different writers would possibly vogue from her life was warranted. She was consistently misrepresented throughout her lifetime and compelled to simply accept the flagrant prejudices of critics and the literary institution. For Petry, the one option to management her story was to stop it from being written in any respect.

For eight years, Barbara Molinard wrote devotedly, committing to the web page the twisted visions that swarmed inside her thoughts. The tales in Panics creep and sprawl, like darkish tendrils of nightmares that received’t finish. They steam with hot-blooded gore, as in a scene the place a pharmacist saws off a person’s balloonish hand. Time is ornery: Characters wait years for trains and planes and different folks; they journey for weeks however by no means arrive at their vacation spot. They’re suffering from anxieties actual and imagined as they battle the opaque logic of social techniques and bureaucracies. Molinard’s tales betray a thoughts keenly conscious of the psychological erosion of contemporary life.

For her half, Molinard appeared considerably bewildered by her tendency towards destruction. She described a divided self: The a part of her that destroyed her work was an “enemy,” and it was this shadowy different who ripped aside and burned her tales.

However certainly destruction provided one thing else, one thing that publishing her work couldn’t: launch from her annoyed toil. The prospect to start anew, on the prime of a clean web page. The potential for conjuring from nothing a singular, stark sentence. As a result of evidently this routine—destroying, rewriting, destroying once more, rewriting once more—could have additionally helped Molinard good her work. Maybe the act of tearing paper was as inextricable to her course of as sitting down on the desk the place she wrote, as the texture of the pen in her hand.

While you purchase a e book utilizing a hyperlink on this web page, we obtain a fee. Thanks for supporting The Atlantic.

Related Posts

- Revolutionizing Hair Take care of Black Girls – Hype Hair

Meet Deangelo Glenn, the visionary celeb hairstylist who's making waves on the planet of hair…

- Self-Care With Endometriosis

SOURCES:Cara King, DO, director, benign gynecologic surgical procedure; affiliate program director of minimally invasive gynecologic…

- CMS’s Coverage on Psychological Well being Therapists Will Work – The Well being Care Weblog

By JON KOLE Almost 66 million People are presently enrolled in Medicare, a quantity that can doubtless swell in…