Health

The Best Museum You’ve By no means Heard Of

In the basement of the Biblioteca Ambrosiana, in Milan, a conservator named Vito Milo had simply utilized a small gel strip to the sting of a 500-year-old drawing as a way to dissolve the glue that joined it to a bigger paper body. Now, with a scalpel, he labored free just a few millimeters of the drawing. I requested Milo what was within the gel, and after he rattled off a listing of elements in Italian, I supplied a layman’s tough translation: “particular sauce.” He smiled and nodded. “Si, particular sauce.”

The drawing was a web page from Leonardo da Vinci’s Codex Atlanticus, and I had been invited to witness the painstaking technique of its conservation. One morning final winter, I descended to the conservators’ laboratory, which occupies a room simply outdoors the steel-and-glass doorway to the Ambrosiana’s gleaming vault. On the backside of the steps, I used to be stopped by an attendant, who took a espresso cup from my arms and positioned it out of hurt’s manner.

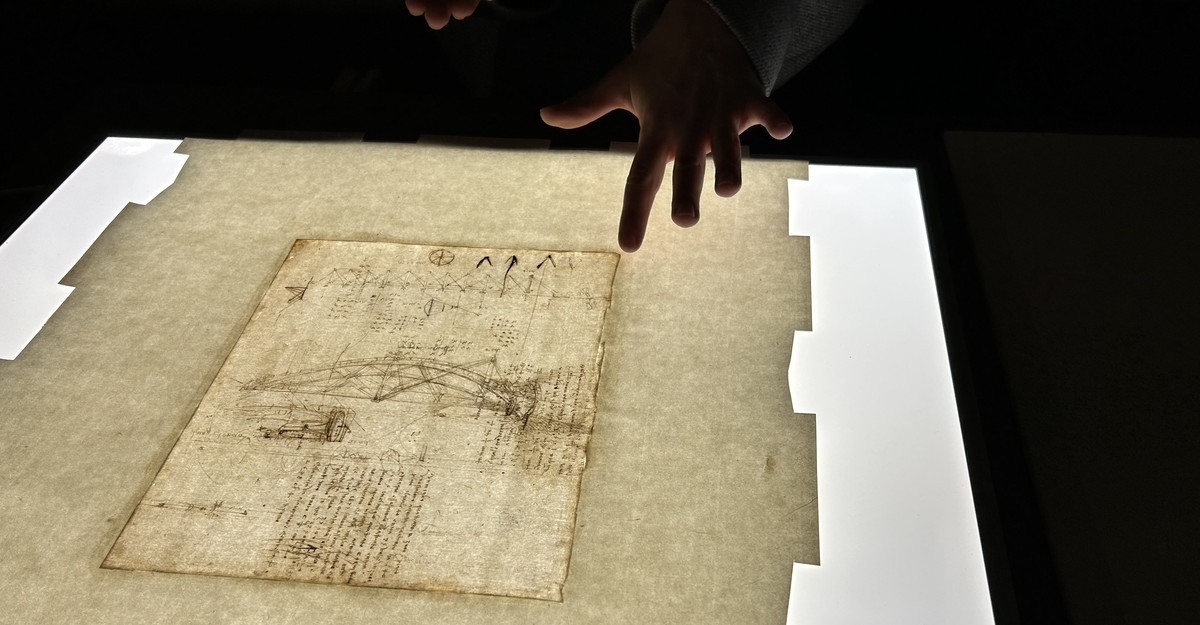

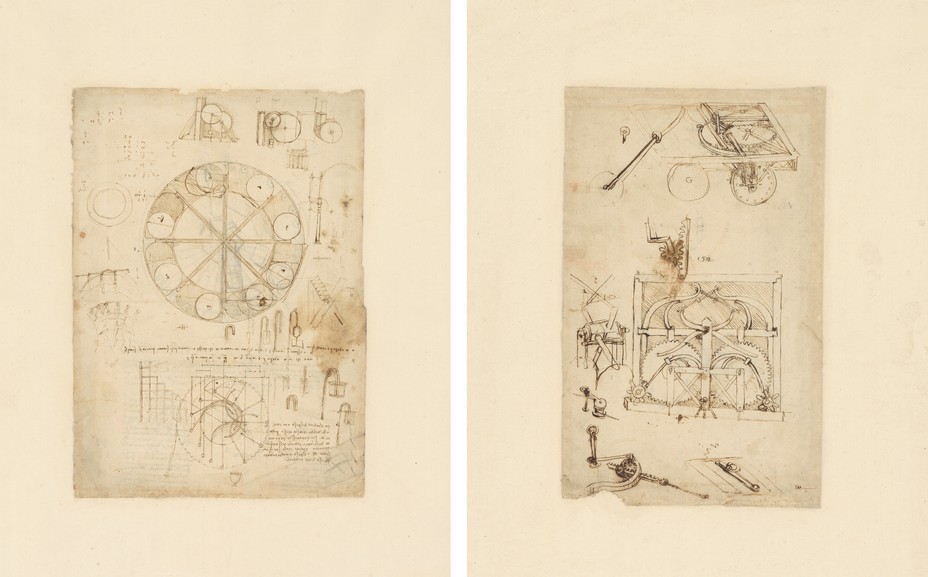

The Codex Atlanticus is a 1,119-page assortment of da Vinci’s engineering designs and technological goals—for flying machines, weapons of struggle, hydraulic gadgets—together with line after line of commentary in a small, exact hand. It’s the largest assortment of works by da Vinci on the earth. The folio pages, as soon as sure right into a single quantity, at the moment are preserved as particular person sheets. The one Milo was bent over—folio 855 recto, with its design for a parabolic swing bridge—rested on the glass of an LED gentle field. Da Vinci’s brown ink stood out sharply in opposition to a glowing background. Wanting carefully, inches from the web page, I might make out the suggestion of a bit of man on horseback atop the bridge, rendered in just a few flicks—a playful addition for scale.

I used to be reminded of this go to to the Ambrosiana once I noticed the announcement of a da Vinci exhibition, “Imagining the Future,” on the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library, in Washington, D.C. Twelve authentic folios from the Codex Atlanticus have simply gone on show—the primary time any of the Codex pages have traveled to the US. The present, which runs via August 20, has understandably gotten consideration: Everybody is aware of what “da Vinci” signifies—his title recognition is common.

“Ambrosiana,” after all, is one other story.

The Biblioteca Ambrosiana is among the world’s least-known nice museums—to the general public, at any fee, if to not students. It occupies a good-looking 400-year-old constructing, just some blocks from Milan’s well-known cathedral, however receives solely about 180,000 guests a yr. The Vatican Museums, in Rome, welcome that quantity each week. The Ambrosiana was based in 1607 by Cardinal Federico Borromeo, the archbishop of Milan, who named it after town’s patron, St. Ambrose, and endowed it together with his personal in depth assortment of books, manuscripts, and artistic endeavors.

The work owned by the Ambrosiana are small in quantity however alternative in high quality: Botticelli, Caravaggio, Titian, Bruegel, and da Vinci himself. The newly restored preliminary cartoon finished by Raphael earlier than he painted The College of Athens—9 ft excessive and 26 ft lengthy—takes up a complete wall of 1 gallery. A monumental research in charcoal and lead-white on grey paper, it’s emotionally extra vivid than the completed fresco. In different galleries, odd relics are preserved behind glass: a lock of hair from Lucrezia Borgia; the gloves worn by Napoleon as he watched his military fall to the Duke of Wellington’s, in 1815.

The books and manuscripts come from everywhere in the world: Borromeo’s gathering sensibility was cultural and cosmopolitan, not spiritual or provincial. The Ambrosiana opened its doorways to anybody who might learn and write—one of many first libraries in Europe to take action. It didn’t chain books in place, as different repositories did, preferring a special sort of safety: The penalty for theft, spelled out on a marble plaque that may nonetheless be seen, was excommunication.

Through the years, the gathering has been augmented, notably by the acquisition of the Codex Atlanticus, in 1637. Da Vinci had died greater than a century earlier, leaving his drawings and notes to one among his college students. Many of those folio pages have been later gathered and sure by the late-Renaissance sculptor Pompeo Leoni right into a quantity whose dimensions gave the Codex its title. (Atlanticus refers to a big paper measurement used for atlases.) The Codex then adopted a picaresque path into the arms of a Milanese nobleman, who bequeathed it to the Ambrosiana.

The folio pages, which span a 40-year interval of da Vinci’s work, are lined not solely with sketches and schemata but in addition with da Vinci’s singular “mirror writing”—he was left-handed, and wrote from proper to left. Not the entire exposition is technical. In a single place, da Vinci scribbled some phrases of reminder to purchase charcoal, for drawing. The Codex Atlanticus accommodates his final identified dated be aware, from 1518: “On the twenty fourth of June, the day of Saint John, in Amboise within the Palace of Cloux.” Da Vinci died in Amboise the next yr, at age 67.

Essentially the most traumatic occasion within the Ambrosiana’s life was the arrival of Napoleon. He crossed the Alps in 1796, and as he made his manner down the Italian peninsula, he despatched wagonloads of plunder again to Paris. The lots of of work and statues taken from Italy—Laöcoon and His Sons, from Rome; Venus de’ Medici, from Florence; the bronze horses atop St. Mark’s, from Venice—would by themselves represent a world-class museum. Actually, they did: the Louvre. Napoleon took books and manuscripts too. A lot of the Vatican archives made its manner north. So did the Codex Atlanticus.

After Napoleon’s defeat, the plundered treasures of Europe have been speculated to be returned to their locations of origin. Some have been; some weren’t. The Vatican couldn’t afford to cart again all of its archives; many paperwork have been bought for scrap and utilized in Paris to make paper or to wrap meat and cheese. France held again many gadgets. Ultimately, solely about half of what was misplaced to le spoliazioni napoleoniche—“the Napoleonic looting”—was truly returned. The Codex Atlanticus was a kind of gadgets. It has been lodged safely within the Ambrosiana ever since.

Safe from marauders, however not from all the things. Through the Nineteen Sixties, specialists took aside the large single quantity of the Codex and reframed every of the 1,000-plus folios with a contemporary paper help, leaving each side of every folio seen when obligatory. When that was finished, the pages have been rebound into 12 smaller volumes. Then, in 2006, a conservator from the Metropolitan Museum of Artwork, in New York, raised an alarm. Analyzing the Codex, she had found black spots on the pages, presumably brought on by mould.

An investigation started. The recognizing, it turned out, was triggered not by mould however primarily by mercury salts, in all probability within the adhesive attaching every folio to its paper help. Fortuitously, the recognizing hadn’t affected the da Vinci folios themselves—solely the paper round them. The Codex volumes have been taken aside. Every affected folio needed to be indifferent from its outdated paper body and given a brand new one. Henceforward, the folios could be preserved as single sheets.

Which brings the story again to Vito Milo, working outdoors the Ambrosiana’s vault. He wore a white lab coat and white latex gloves. His options have been bottom-lit by the golden glow from the field. As he labored, he spoke concerning the intimacy of this connection to da Vinci: how one can see his erasures, his errors, the little notes he wrote to himself. It might take a few month, he mentioned, earlier than this explicit drawing was freed from its outdated paper help, cleaned of the outdated glue, and reaffixed with a brand new sort of adhesive to a brand new help. Then he could be onto the following folio.

One consequence of unbinding the Codex is that the folios could possibly be digitized. One other is that particular person sheets can journey and be displayed, making doable exhibitions such because the one now in Washington. On the Ambrosiana itself, a rotating collection of a dozen pages is now all the time on public view in show containers, climate-controlled and bulletproof. The protocols are strict: To forestall deterioration introduced on by pure gentle, a folio might be exhibited for less than three months. Then it should relaxation in darkness for 3 years.

The Ambrosiana stays an ecclesiastical establishment, and Alberto Rocca, the director of its image gallery, is a Catholic priest. I met with him for an hour in a Baroque ground-floor workplace, its ceiling excessive, its bookshelves sagging. A member of the Ambrosiana’s governing School of Fellows, Rocca oversees not solely the image gallery but in addition a community of packages for far-flung students. He’s trim {and professional}. Take off the Roman collar, and he could be at residence among the many workers on the Rijksmuseum or at Christie’s.

Our dialog ranged over many matters. Wanting again: how uncommon Borromeo’s cross-cultural outlook was on the time, and likewise how uncommon his want to make books freely out there to the general public. Wanting ahead: the issue of sustaining an establishment of this type. The Ambrosiana’s artwork gallery can help itself; the analysis library, with its 1 million books and 40,000 manuscripts, can’t. Europeans, Rocca famous, don’t have the philanthropic custom that People do.

It’s mentioned that Napoleon himself walked out of the library with Petrarch’s personal copy of Virgil below his arm. (It was ultimately returned.) It’s definitely true that some materials by da Vinci didn’t come again, and sure by no means will. Rocca didn’t want to dwell on historical past, even when Napoleon clearly had so much to reply for. On the plus aspect, Rocca mentioned, “no less than we have now the gloves he had when he was defeated at Waterloo.”

Related Posts

- If You’ve Ever Heard a Voice That Wasn’t There, This Might Be Why

Some years in the past, scientists in Switzerland discovered a method to make folks hallucinate.…

- Cancelled plan? You’ve obtained protection choices

Printed on December 19, 2013For tens of millions of Individuals high quality, inexpensive protection is…

- Metastatic Breast Most cancers: Be Heard

Picture Credit score: FatCamera / Getty PhotosYale Faculty of MedicationNorthwestern Medication Most cancers Heart DelnorMoffitt Most…