Health Care

Photographer Corinne Dufka’s New Guide Tells the Story of Warfare

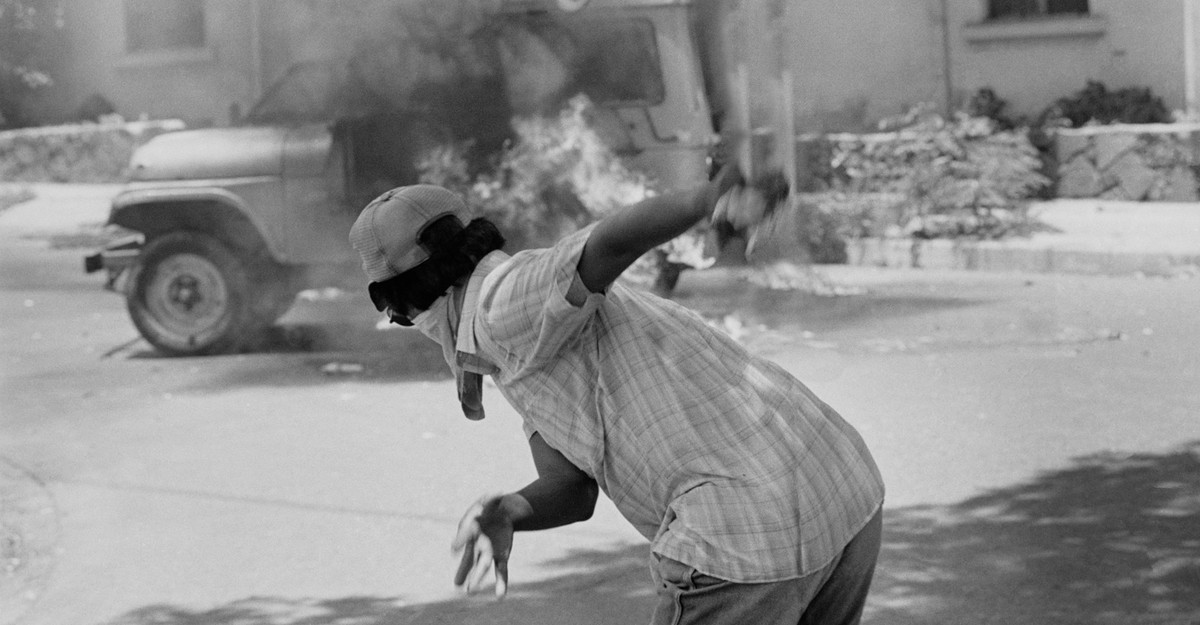

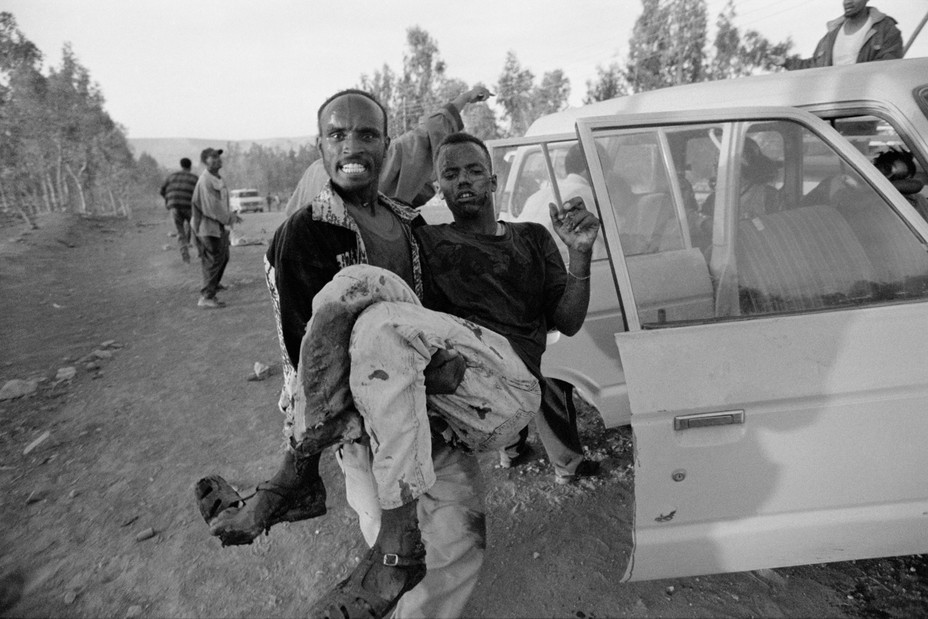

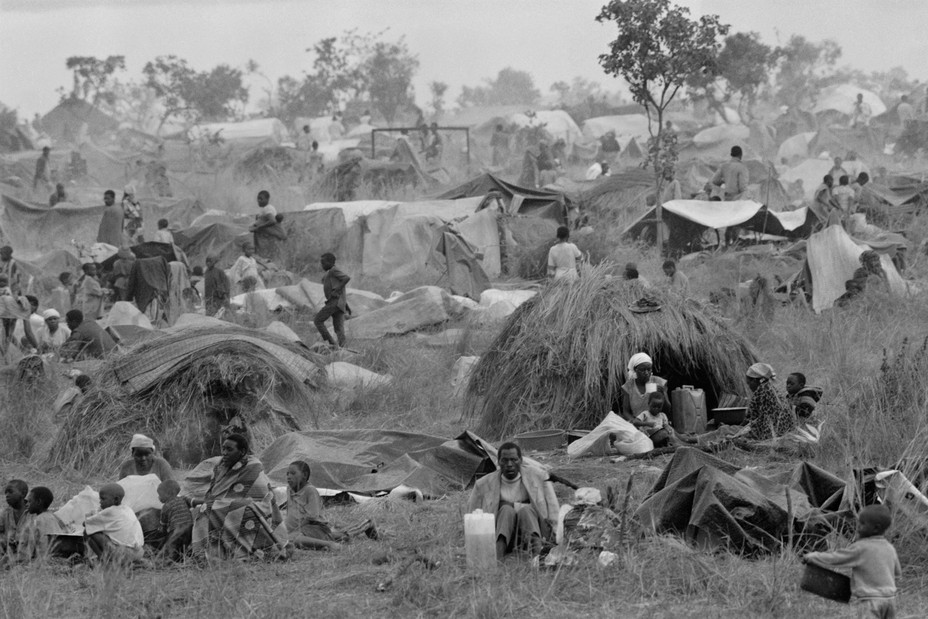

This Is Warfare advanced out of my work as a photographer masking a number of the bloodiest conflicts of the late twentieth century. The imagery is just not fairly, nor might it’s. However seeing it—wanting squarely on the distress delivered by leaders who promised to do good for his or her folks—is necessary. Greater than that, refusing to see it, whether or not out of private or political discomfort, is a type of misinformation.

The guide tells the story of battle via the experiences of each civilians and combatants. The civilians have been coming into a labyrinth of grief that they’d occupy for the remainder of their lives. Most of the combatants naively seen battle as a possibility, solely to find that their our bodies have been mere fodder for the highly effective.

I first picked up a digital camera in El Salvador within the mid-Nineteen Eighties. I photographed the our bodies that the infamous dying squads left on road corners at evening. Within the early ’90s, I used to be posted to the previous Yugoslavia, and later, to Africa. Unscrupulous leaders, pushed by ego, revenue, and ethnic, spiritual, or nationalist agendas, waged battle on civilians and turned villages into killing fields.

To be a battle photographer is to forge an intimate relationship with the useless and dying. We occupy disparate worlds, empathizing with these reeling from profound loss, even whereas interacting with those that take human lives. To witness brutality is to maintain psychic harm: What the attention sees, the mind data and can’t erase. For the battle photographer, the conjunction of horror and alternative provides an extra twist.

I understood this ambivalence whereas photographing road battles between rival militias in Monrovia, Liberia, in 1996. I came across a person foraging for meals in a destroyed store. A bunch of fighters pounced on him. They ignored his pleas for mercy as they dragged him via the streets and, moments later, executed him.

Growing the movie within the quiet of my lodge room, I retched as I relived what I had seen an hour earlier: A bunch of youngsters stripped an unarmed man who didn’t count on to die that day to his underwear and socks and murdered him in a ditch for no obvious motive. However I used to be additionally gratified once I found that the pictures have been in focus and highly effective. I knew they’d distinguish my profession, they usually did.

My life as a battle photographer was punctuated by such moments of cognitive dissonance. Photographing the wounded in frenetic hospitals, moms rocking in grief, troopers stepping on land mines, and militiamen taunting, torturing, and killing each other, I wrestled with the notice that probably the most painful episodes of those folks’s lives have been additionally events on which part of me thrived.

I produced this work at a frenzied tempo: airport, battle, {photograph}, airport, battle, repeat. My photos uncovered atrocities, signaled the beginnings of epidemics, and set off alarms in world capitals. However because the years handed, I turned conscious that with every battle, what I gained in stature as a photojournalist, I misplaced in human empathy.

The belief drove me from my career and led me to a different: documenting battle crimes in West Africa for a human-rights group by way of witness testimony. Immersing myself in a world of coverage, justice, and state constructing, I labored to cease the atrocities I had witnessed as a battle photographer. I had a daughter, I fostered a son, and I didn’t look again.

I stuffed packing containers of negatives from my photojournalism days into footlockers. After which, 20 years later, I pulled them out once more and noticed the pictures I’d made via a special prism. I had spent a long time analyzing how states fail and why wars persist. Elevating kids had perpetually altered my understanding of the aching magnitude of loss, and the way this loss, if not managed, drives ever extra violence.

This Is Warfare represents a deeply private journey—a reckoning with what I witnessed over a tumultuous decade and the toll it took on me. However the guide can also be my contribution to the historic report of the conflicts lined and the function girls have performed in battle photojournalism.

My work can also be a name for reflection on why conflicts relapse. Method too most of the photos I took a long time in the past may very well be taken at the moment. On the time of writing, battle has returned to Sudan, whereas within the Democratic Republic of Congo, it by no means left. El Salvador’s ideological battle has been changed by bloody gang violence. In Bosnia, ethnic tensions are on the rise. In too many locations, the elements that drove conflicts in a long time previous—predatory governance, corruption, and crushing poverty—proceed unabated. These photos are a reminder that the elements of the world which might be damaged nonetheless want a sturdy repair.

To be the final particular person a dying lady, or a condemned man, sees on Earth is a morally uncomfortable factor, but additionally one which conveys a sure accountability. Warfare photographers are historians, artists, trespassers, and emotional bandits with sophisticated motives, some virtuous, some not. The pictures themselves, at their finest, extract the essence of battle, beseeching the viewer to honor those that have perished and to guard the remainder of humanity from its worst, most abject failure: its capability for battle.

This text was excerpted from Corinne Dufka’s guide This Is Warfare: A Decade of Battle: Images

If you purchase a guide utilizing a hyperlink on this web page, we obtain a fee. Thanks for supporting The Atlantic.

Related Posts

- Birthdate Co. Gives a Personalised Astrological Beginning Chart E book – StyleCaster

All services featured are independently chosen by editors. Nonetheless, StyleCaster could obtain a fee on…

- Keiasha’s weight reduction story | Black Weight Loss Success

Transformation of the Day: Keiasha shared her weight reduction story with us. She realized that the size…

- 7 Reasons to Book a Wellness Retreat

Imagine waking up feeling energized and fresh in a clean, luxurious hotel room before heading…