Health Care

My Lifelong Obsession With the Worst Group within the NFL

Even now I can nonetheless see him, the person in gold and white, streaking down the sideline on their lonesome.

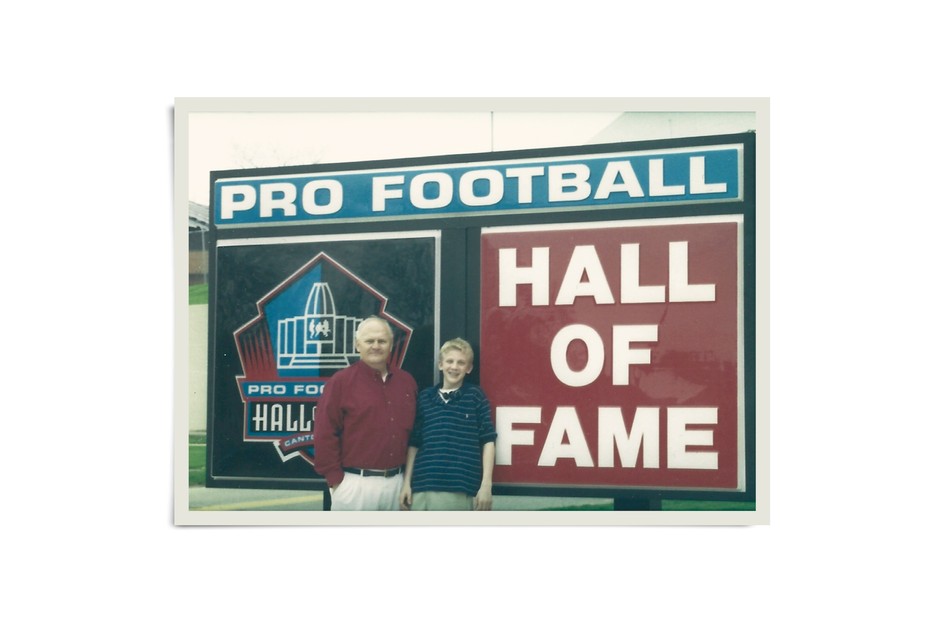

After which the ball was within the air. It hung up there for what felt like my total childhood, spiraling in gradual movement, touring 50 yards in whole. I keep in mind gasping. Only a few minutes earlier, my favourite group—my first real love—the Detroit Lions, had taken a three-point lead over the hated Inexperienced Bay Packers. It was the primary spherical of the 1993 NFC playoffs, and it was my first time at a Lions recreation. The sound of the 80,000 souls crammed into the Pontiac Silverdome—a glorified warehouse within the blue-collar suburbs of Detroit—was deafening, a roar of humanity not like something I’d ever heard, the decibel stage shaking the cement beneath our bleacher seats. However now, with lower than one minute remaining, because the soccer dropped into the arms of Sterling Sharpe, the person in gold and white, there was silence. The Packers’ unproven younger quarterback, Brett Favre, had simply made probably the most spectacular landing throw of his profession and eradicated the Lions from the playoffs.

I used to be inconsolable. The Lions had been the higher group; even a child may see that. We’d out-gained the Packers, out-converted them, out-played them. However we’d misplaced anyway—in dramatic, dream-shattering vogue. It was an excessive amount of for my 7-year-old feelings to course of. So, I wept. First within the stands as time expired, then within the swarming, beer-soaked concourse as my household looked for the exit, and for your entire hour-long automobile trip residence. Lastly, as we pulled into our driveway, my dad spun the radio knob leftward, turning down the postmortem present. “It’s only a recreation,” he mentioned, smiling gently. “We’ll win the subsequent one.”

It was the one lie my dad ever informed me.

A yr later, the Lions met the Packers once more within the playoffs—and, once more, the Lions misplaced. The subsequent time they reached the postseason, they misplaced. And the time after that. And the time after that. Since falling to Inexperienced Bay that ill-fated evening, the Lions have appeared in seven playoff video games. They’ve misplaced each single one. This streak of futility, going greater than 30 years with out a playoff win, is unmatched within the annals of the Nationwide Soccer League. However the historic context is even worse. Since successful an NFL championship in 1957—a decade earlier than the primary Tremendous Bowl was performed—the Lions have gained only one playoff recreation, within the 1991 season, in opposition to the Dallas Cowboys. That’s proper: one playoff victory because the Eisenhower administration.

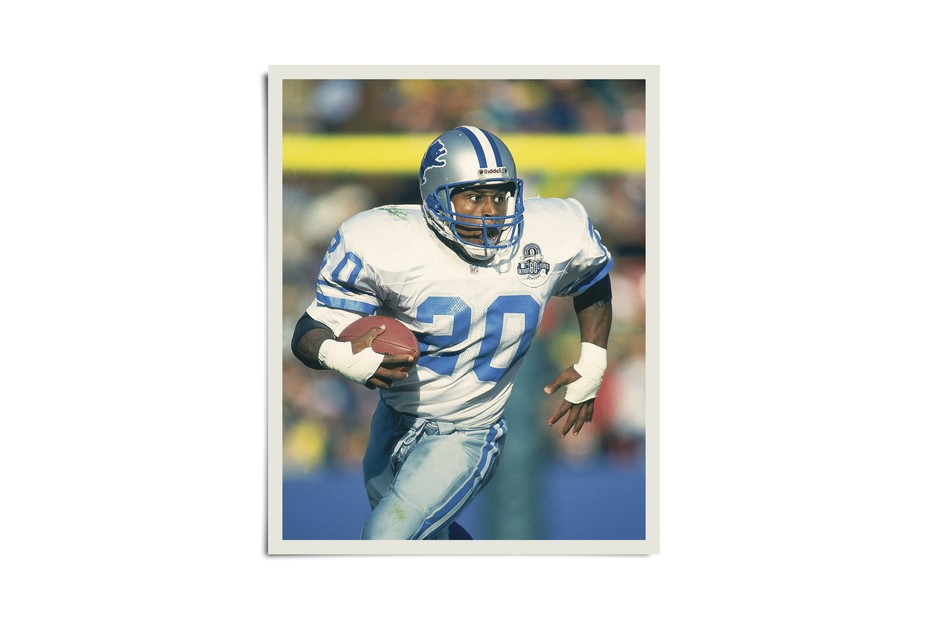

Each loss I’ve witnessed has been painful, however none greater than that Packers recreation. The Lions have been stacked with elite expertise: linebacker Chris Spielman, offensive sort out Lomas Brown, return specialist Mel Grey. And naturally, probably the most electrifying participant in soccer, operating again Barry Sanders. The group was poised to turn into one of many league’s greatest. However that loss to the Packers broke them. Immediately, Favre and his Inexperienced Bay squad have been ascendant, racking up division titles and convention championships and successful a Tremendous Bowl. In the meantime, the Lions fell aside. In the summertime of 1999, on the eve of coaching camp, Sanders floored the soccer world by saying his retirement. Regardless of being within the prime of his profession—one season away from breaking Walter Payton’s dashing report—he was worn down by the shedding. Two years later, the Lions introduced in Matt Millen to rebuild the group as president and CEO. What ensued was probably the most disastrous tenure the soccer world had ever seen: The Lions went 31–97 through the eight seasons Millen oversaw the roster, solidifying our repute because the laughingstock {of professional} sports activities. In 2008 we made historical past, going winless with a report of 0–16.

Samuel G. Freedman: A soccer memoir, with tears

It was the worst season an NFL group had ever performed—and I didn’t miss a single snap. Each Sunday that fall, throughout my final semester at Michigan State College, I watched, yelled, seethed, prayed, and in the end witnessed the Lions come up brief. A couple of minutes later, as predictable as a late-game turnover, the telephone would ring. My dad wished to examine on me. We’d commiserate for a short time, then speak about different issues. Each dialog ended the identical manner. “We’ll win the subsequent one,” he would say.

By then I used to be sufficiently old to comprehend one thing: Dad didn’t truly consider we’d win the subsequent one. He wasn’t predicting a breakthrough victory. He was educating me methods to deal with defeat; he was urging me not to surrender hope. He was assuring me that, it doesn’t matter what, we’d speak once more the next Sunday.

A couple of summers in the past, the day after Dad died, I stood outdoors a funeral residence with my brother Brian. Our father’s passing had been sudden and surprising; each of us have been in a daze. After standing there in silence for some time, my brother let loose a sigh. “Man,” he mentioned, “Pop by no means bought to see the Lions win.”

Brian was proper: For all these many years of fanhood, for all these Sunday-evening pep talks, for all these life classes drawn from watching his group lose, Dad had by no means been rewarded with an actual winner.

I considered that once I moved my circle of relatives again to Michigan shortly after the funeral. I considered it once I purchased season tickets. I considered it final summer season, when my spouse and I took our son Lewis to his very first Lions recreation. He was nearly 7 years previous—the age I’d been when my coronary heart was damaged that evening in opposition to the Packers. This was only a preseason recreation, however it delivered thrill after thrill. The Lions pulled away late; the house stadium, now Ford Discipline in downtown Detroit, pulsated with cheers. Lewis regarded euphoric.

After which a well-known flip of occasions. The Lions, unforced, fumbled the ball away. The Atlanta Falcons, on a fourth down with 90 seconds remaining, scored a miraculous landing. The stadium fell right into a hush. Lewis regarded up at me. “What simply occurred?” he requested, his voice quivering. “Did we lose?”

On the automobile trip residence, after we’d pacified Lewis with sweet and a stuffed mascot from the stadium, my spouse turned to me. Her tone was severe. As a training youngster therapist—and because the spouse of a die-hard Lions fan—she knew what emotional trauma regarded like. She was apprehensive about our son.

“Are you positive,” she requested me, “that you just wish to do that to him?”

I had by no means thought of it elective. The Lions have been in my DNA. A few of my earliest, most vivid recollections—fashioned at no older than age 3—are of my dad and older brothers erupting with screams inside our cramped front room, usually horrifying me to tears. I might peek in and discover them whooping and high-fiving across the small tv set, nearly at all times in response to some laws-of-physics-defying maneuver and subsequent landing dash by Barry Sanders. Dad hadn’t grown up a giant soccer fan. However the yr we moved to Michigan was the identical yr the Lions drafted Sanders; earlier than lengthy he and my brothers have been hooked, and ultimately I used to be too. Sundays turned sacrosanct: Dad preached at our church within the morning, then raced residence to fulfill us for the afternoon kickoff. We scampered outdoors afterward to re-create the motion, pretending to be our favourite gamers, then got here in for dinner and rehashed the outcomes. I can scarcely keep in mind feeling so content material.

After all that fandom could be handed right down to my three sons. A framed picture of Sanders had hung over the crib in our youngsters’ nursery; the partitions of their room have been painted Honolulu Blue, the singular shade of Detroit’s residence uniform. My boys would develop up obsessing over each draft decide, each free-agent acquisition, each teaching change, similar to I had. We’d watch the video games collectively after they have been younger, and as soon as they ventured out into the world, we might speak on Sunday evenings.

My spouse knew what she’d signed up for. Again after we began courting, I needed to clarify to her the ethical prerequisite of “The Mane Occasion,” an annual road-trip extravaganza with three of my closest childhood mates, through which we drained our meager financial institution accounts to observe the Lions play (and nearly at all times lose) an away recreation. When my spouse and I bought married, the place playing cards for the reception have been refashioned Lions tickets. The subsequent day, for our honeymoon, we hosted an enormous tailgate outdoors Ford Discipline. (In equity, we lacked the funds to go wherever else.) She was an incredible sport about it, sporting a veil to match her Ndamukong Suh jersey, proving that I married probably the most superb lady on the planet.

Over time, nonetheless, her persistence waned. The evening Lewis was born, I used to be glued to the NFL draft contained in the supply room, a distraction that for some purpose she discovered irksome. Minutes after Lewis emerged, I carried him over to the tv, swaddled in blankets, and collectively we watched the Lions choose Taylor Decker, an offensive sort out from Ohio State College. It was a polarizing decide: We don’t like Buckeyes a lot in Michigan, and plus, the Lions desperately wanted expertise on the defensive facet of the ball. I cradled my new child in a single hand and traded offended texts with family and friends within the different, baptizing Lewis right into a life he by no means requested for.

Some seven years later, after that preseason loss to the Falcons, I wrestled with my spouse’s query. Rooting for the Lions had given me some fantastic recollections, but in addition some punishing ones. This wasn’t merely about choosing a favourite group for my kids; this was about passing down a painful existence. Each group wins some video games and loses others, however not each group is a nationwide punch line and annual bottom-dweller. Was it actually truthful, I questioned, to pressure that on somebody?

I made a decision to again off. If Lewis and his brothers have been to turn into followers, it wouldn’t be their dad’s dictate. They wanted to decide on the Lions on their very own. Frankly, I didn’t see that occuring anytime quickly. The regime that took over in 2021—head coach Dan Campbell and normal supervisor Brad Holmes—had inherited the worst roster within the league. Of their first season, they’d gained simply three video games. In 2022, after my paternal second of readability, the group began the yr by shedding six of its first seven video games. At this fee, I figured, it could be simple to abstain from pushing Detroit soccer on my boys.

However then the strangest factor occurred: The Lions began successful.

The offense had proven indicators of being explosive; now, halfway via the season, it was unstoppable, hovering towards the highest of the league leaderboard in yards and factors per recreation. The protection had been dreadful; now it was scrappy, tenacious, bettering each week. Campbell, the Hercules-size coach who’d performed 10 years within the league as a good finish, had splashed a brand new, one-word group motto—GRIT—all throughout the Lions facility, even printing it on hats and shirts for the gamers to put on. Some followers seen this as a token rebranding effort. However because the season progressed, our franchise reworked into one thing unrecognizable. These Lions didn’t give an inch to their opponents. They have been mentally powerful; they performed with swagger, anticipating to dominate each time they took the sector. Detroit turned probably the most harmful group in soccer, successful seven of its final 9 video games and by some means, regardless of the terrible begin, sneaking into playoff competition. It might all come right down to the season finale, a prime-time recreation in Inexperienced Bay in opposition to the Packers.

I had held agency on my promise to not indoctrinate the boys. However I couldn’t comprise my very own exhilaration: After reserving our tickets for Sunday evening, January 8, 2023, at fabled Lambeau Discipline, my “Mane Occasion” crew traveled north.

The Packers had owned this rivalry my total life. First it was Favre, the Corridor of Fame quarterback, who had killed us; then it was his successor, Aaron Rodgers, a future Corridor of Famer himself. Throughout one stretch, Detroit misplaced 24 consecutive video games in Inexperienced Bay, the longest highway shedding streak in NFL historical past. Getting overwhelmed was dangerous sufficient. Worse nonetheless was the “Similar Outdated Lions” narrative we couldn’t appear to flee, owing to legendary choke jobs and unjust endings: the “finishing the method” non-catch in Chicago, the 10-second runoff in opposition to Atlanta, the picked-up pass-interference flag in Dallas. And no group within the NFL appeared to learn from our curse fairly just like the Packers.

Minutes earlier than kickoff in Inexperienced Bay, a 3rd playoff contender, the Seattle Seahawks, gained their recreation following a number of atrocious fourth-quarter calls, eliminating the Lions from playoff competition however protecting Inexperienced Bay alive. All of the Packers needed to do was win, on their residence subject, to get in. The champagne bottles started popping round us at Lambeau. The Lions, most individuals assumed, would mail it in.

Learn: Offended soccer followers maintain punching their TVs

However they didn’t. Within the gutsiest efficiency I’d ever seen from my group, Detroit smacked Inexperienced Bay round inside its personal home. Regardless of having nothing to play for however satisfaction—and the prospect to maintain their nemesis out of the postseason—the Lions hounded Rodgers all evening, sacking him twice and sealing his profession in Inexperienced Bay with an interception on his ultimate drive. Because the Packers trustworthy emptied out of the stadium, my mates and I joined hundreds of Lions followers in dashing towards the decrease bowl, forming a hoop of Honolulu Blue across the subject, dancing and singing and hugging strangers within the snow. It was the very best second of my life as a Lions fan.

Using the momentum from their late-season surge, the Lions turned a league darling headed into the 2023 marketing campaign. A number of high free brokers signed on to play for Campbell. Nationwide pundits picked Detroit to win the NFC North—one thing we have now but to do because the NFL realigned its divisions 20 years in the past. Oddsmakers in Las Vegas took extra bets on the Lions to make the Tremendous Bowl than they did on another group within the convention.

This was not some cute, try-hard Cinderella story. When the NFL launched its 2023 schedule, the opening recreation of the season—Thursday, September 7, in prime time, all of the buildup and all of the eyeballs—featured the Kansas Metropolis Chiefs, the defending Tremendous Bowl champions, enjoying at residence. Their opponent: the Detroit Lions.

On the primary day of coaching camp this July, Campbell informed reporters that the “hype practice” surrounding his group was “uncontrolled.” However it wasn’t the hype that scared me. It was one thing else—a sense I couldn’t make sense of. With some trepidation, I made a decision to take a look at coaching camp myself.

Barry Sanders doesn’t have the strikes he as soon as did. The immortal operating again, whose jukes and spins and stop-and-start cuts left a technology of linebackers looking for their jockstrap, couldn’t shake the mob of individuals searching for an viewers. It was a sweltering August afternoon and Sanders, now 55 years previous, had dropped in on Lions headquarters in Allen Park. The Lions have been internet hosting the New York Giants for a joint scrimmage forward of their preseason recreation later within the week, and a crowd of a number of thousand followers swarmed the observe facility. When phrase bought round that Sanders was right here, everybody—gamers and coaches from each groups—lined up, pointing and whispering like little youngsters, ready to shake his hand. By the point Sanders bought to me, underneath a shaded pavilion subsequent to massive steel tubs crammed with ice, he regarded exhausted.

Nothing was forcing Sanders to be right here—no sponsorship settlement, no contractual obligation with the membership. He was completely satisfied to go to with everybody, to signal autographs and snap selfies. However actually, he’d come to observe soccer. He’d come to see his group.

Given the circumstances of his departure years earlier—the retirement letter he faxed right into a newspaper, the excitement round his feud with the group, the gap he stored within the aftermath—one may assume that he’d need nothing to do with the Lions. It’s laborious to overstate simply how devastating his retirement was to the franchise. Each hard-core Lions fan can keep in mind the place they have been after they came upon. I used to be inside a Denny’s, consuming eggs with my dad, when a man sprinted inside, having simply heard the breaking information over the automobile radio. “Barry’s retiring! Barry’s retiring!” he cried. We sat there in disbelief.

Sanders heard these sob tales within the years that adopted. However it wasn’t till his kids reached a sure age that he really understood the emotion behind them. He had made southeast Michigan his residence, placing down roots and elevating his youngsters there. He had by no means pressured them to observe any specific sport, cheer for any specific membership. But they turned soccer followers. They turned Lions followers. And so did he. The Corridor of Famer may not assist himself: Each Sunday within the Sanders home now centered on the group he’d left behind. He noticed his sons crushed in all of the acquainted methods; he watched them mourn the surprising retirement of one other Lions celebrity, large receiver Calvin Johnson, bringing the expertise full circle. But all of the whereas, Sanders and his household continued to cheer.

“It’s one thing that I grapple with, and it’s simply laborious to elucidate,” Sanders informed me. “This group issues to us. You understand what I imply?”

I requested whether or not he and his sons had ever thought of switching allegiances. Sanders cocked his head to the facet, rumpling his forehead.

“No. No, no, no,” he mentioned. “These individuals who have been loyal, individuals who have been there each step of the way in which—that’s the fantastic thing about the sport, I feel. There are not any ensures. However they nonetheless consider.”

Typically that magnificence offers solution to torment. On the far finish of the observe subject, a person with a flowery job title—particular assistant to president/CEO and chairperson—stalked the sideline with a notepad in his proper hand. Most front-office varieties put on fits and ties. However this man was wearing all black: exercise pants, hooded sweatshirt, 50-pound weighted vest, all of it made extra conspicuous by the mid-80s warmth. It was Chris Spielman.

The anchor of Detroit’s protection within the Nineties, Spielman performed temporary stints in Buffalo and Cleveland earlier than retiring due to accidents. He went into the printed sales space and spent the subsequent 20 years offering shade commentary for school and NFL video games. He was completely satisfied, making a high-quality dwelling, free of the weekly stresses of a win-loss report. After which the decision got here. It was late 2020, and the Lions have been coming off their third consecutive last-place end. The group’s proprietor, Sheila Ford Hamp—great-granddaughter of Henry Ford and daughter of William Clay Ford Sr., who’d bought the franchise outright in 1964—informed Spielman the Lions wanted a tradition change. She was looking for a brand new coach and normal supervisor, however first she wanted a soccer consigliere, somebody who may assist information these hires, who may join the entrance workplace to the locker room to the X’s and O’s on the sector. His thoughts was made up earlier than she’d completed the pitch.

“Loyalty to this group was in all probability the one factor that might have drawn me out of the sales space,” Spielman informed me.

There was extra to it than loyalty, although. As we spoke, and he drifted again to his enjoying days in Detroit, I sensed an absence of peace concerning the man. He talked about “letting down the fan base.” He mentioned the losses—particularly to Inexperienced Bay within the playoffs—“at all times hang-out me.” At one level, he gazed off within the distance, choking again emotion as he muttered, “My profession was a failure.”

Skilled athletes are typically regarded as detached to the plight of followers—millionaire mercenaries who gather a paycheck and transfer on to a brand new metropolis for a fair larger one. But right here was Spielman, a god of the gridiron—the primary high-school participant ever to seem on a Wheaties field; a two-time All American in school; a four-time Professional Bowler within the NFL—nonetheless distraught, 30 years later, about what may have been. And it wasn’t just because he by no means gained. It was as a result of he by no means gained right here.

“I’ve a lot respect for the parents who’ve hung in there. I felt I owed them one thing,” Spielman mentioned of his choice to return to Detroit. He referred to as it “unfinished enterprise.”

At this time the budding star of the Lions protection is Aidan Hutchinson, a second-year move rusher who led all rookies in sacks final season and appears poised to turn into one of many league’s premier defensive gamers. He’s an area child, born and raised in Plymouth, drafted out of the College of Michigan. He calls it “divine timing” that the Lions misplaced 13 video games the season earlier than he turned professional, permitting them to snag him with the No. 2 total choice in final yr’s draft.

There is only one hitch in Hutchinson’s homecoming story: He didn’t root for the Lions as a child.

“I imply, it was laborious to be a Lions fan rising up,” the 23-year-old informed me after observe sooner or later, a sheepish grin spreading throughout his face. “The boys have been at all times struggling.”

Hutchinson is aware of that the Lions are one thing of a faith in southeast Michigan. His mates cherished them. He grew up 20 minutes from group headquarters. And but, he selected to cheer for the New England Patriots—the winningest franchise within the trendy historical past of the NFL.

“My dad was by no means a giant Lions fan. That’s the place I didn’t get it,” Hutchinson mentioned. “He grew up in Texas; he was at all times a Houston Oilers fan.” When that franchise moved to Nashville within the late Nineties, the elder Hutchinson—who starred on the College of Michigan himself, then stayed within the Detroit suburbs to boost his household—turned a pigskin itinerant. He adopted everybody, and though he hardly ever missed a Lions recreation, he couldn’t convey himself to put money into the house group. By the point Aidan was sufficiently old to observe alongside him, a fellow Michigan alumnus named Tom Brady was establishing a dynasty in New England. And so the Hutchinsons turned Patriots followers, reveling in Tremendous Bowls from afar as their neighbors right here hankered for a mere playoff win.

Mark Leibovich: The quiet desperation of Tom Brady

I requested Aidan, now that he’s a Lion, if he felt badly about not supporting his residence group sooner.

“Not essentially,” Hutchinson replied, preventing a smirk. “I’m completely satisfied I’m on the group now.”

The implication was apparent sufficient. Nothing was misplaced by ignoring the Lions all these years—the blooper-reel lowlights and the humiliating headlines—as a result of in sports activities, successful is what makes fanhood worthwhile.

Plenty of individuals consider that. I used to query my very own sanity, questioning why I subjected myself to such assured distress Sunday after Sunday, season after season, decade after decade. Greater than as soon as I fantasized about rounding up my memorabilia—the jerseys and autographs, the helmets and framed images, the previous packages and saved ticket stubs—then dousing it in gasoline and setting it ablaze, escaping this abusive relationship as soon as and for all.

Why didn’t I?

For the longest time, I informed myself it was as a result of I’m cursed. I informed myself that the second I walked away from the Lions, they’d begin successful and successful large, driving me to a completely totally different stage of insanity.

However that’s not the true clarification. Embedded within the psyche of a sports activities fan is a perception that these groups say one thing about us; that though we are able to’t affect the outcomes—any greater than we are able to management the climate or an financial downturn or a coronary heart assault stealing a member of the family—we discover in them a private significance that echoes past the field rating. There’s a purpose the Lions—not the Pink Wings, or the Pistons, or the Tigers, all of whom have been winners in my lifetime—are the favourite sons of Detroit. In a metropolis that may’t appear to catch a break, individuals discover frequent trigger in rallying across the group that greatest displays their very own story.

For Lions followers—and, I began to comprehend, for Lions gamers—the entire shedding has fashioned bonds that successful by no means may.

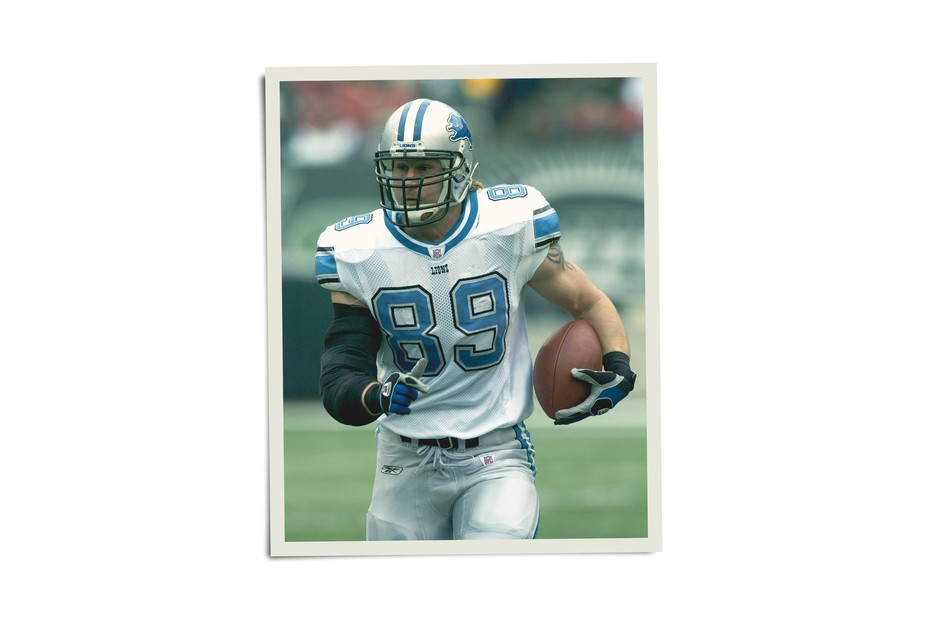

“A hundred percent,” Taylor Decker, the left sort out whom the Lions had drafted when Lewis was roughly quarter-hour previous, informed me at coaching camp. “It makes you notice who you may depend on, who has your again, who you may belief.”

Now coming into his eighth season—he’s the longest-tenured participant on the membership—Decker informed me, “I’ve turn into a person within the metropolis of Detroit.” A part of that maturation owes to experiencing defeat: Coming from Ohio State, the place he gained a nationwide championship earlier than turning professional, Decker had by no means tasted the setbacks that might mark his first six years in Detroit. Unusual as it would sound, he appears grateful for these setbacks now.

“In at the moment’s society, I really feel like quitting and taking the straightforward manner out has been normalized,” Decker mentioned, citing gamers who demand trades or refuse to re-sign with a struggling group. “I do suppose there’s one thing to be mentioned for seeing it via and going via these laborious occasions.”

Scott Stossel: Successful ruined Boston sports activities fandom

Hanging across the Lions facility this summer season, speaking with gamers, officers, and journalists who cowl the group, I assumed concerning the irony of my tortured relationship with the Lions. Would I’ve talked with my dad each Sunday evening if our group was regular, unspectacular, business-as-usual aggressive? Would my brother Brian and I dissect each draft decide if our group was coming off back-to-back division titles? Would my mates and I trouble with The Mane Occasion if our group had already gained a Tremendous Bowl?

Aidan Hutchinson felt sorry for us long-suffering Lions followers. However I began to really feel sorry for him. Dropping is tough and sometimes harrowing. However it’s additionally inevitable. And what we take from these losses is exactly what’s essential to win: resolve, perseverance, and, sure, grit. That’s what my dad taught me earlier than I misplaced him. And that’s what I hope to show my sons, who, sooner or later, are going to lose me.

With the season opener in Kansas Metropolis drawing close to, and my self-imposed ban on proselytizing the boys nonetheless in place, there was an uncomfortable fact to confront. Perhaps I wasn’t afraid of them inheriting a loser. Perhaps I used to be afraid of them inheriting a winner.

When I shared my epiphany with Brad Holmes, he was stone-faced at first. After which, slowly, he began to nod.

“I used to be doing loads of analysis not too long ago on warmth publicity and chilly publicity—like, deliberate warmth publicity along with your physique. And loads of analysis says that when your molecules undergo, it truly makes your molecules even stronger,” Holmes, the Lions’ normal supervisor, informed me one latest afternoon because the group practiced in a misting rain. “It’s type of like while you’re rising wine. When the grapes are uncovered to intense temperatures, it truly produces a better-quality wine. You understand what I imply?”

Sure, I knew what he meant—not concerning the grapes or the molecules, essentially, however concerning the metaphorical level he was making. Holmes had seen his share of adversity. Raised in a soccer household—his father performed for the Steelers, his cousin performed for the Rams, and his uncle, naturally, performed for the Lions—Holmes turned a defensive lineman at North Carolina A&T and briefly harbored NFL aspirations of his personal. After which a violent automobile wreck after his sophomore season practically killed him. Holmes spent every week in a coma, struggling a ruptured diaphragm and a stroke from the violence of the collision. Despite the fact that he battled again, ultimately rejoining the soccer group and enjoying out his school profession, the dream was over.

Holmes nonetheless wished a bit of the NFL. He despatched copies of his résumé to each group, begging for an internship in somebody’s scouting division. “And each group informed me, ‘no, no, no, no, no,’” he recalled. Holmes took a job at Enterprise Lease-A-Automobile to pay the payments, however stored on pushing. “That’s simply type of how I’m wired,” he informed me. “I embrace the darkness.”

After forcing his foot into the door with the Rams—Holmes began as an intern within the public-relations division—he ultimately rose to turn into the director of faculty scouting, serving to to assemble arguably probably the most gifted roster within the league. That roster gained a Tremendous Bowl in 2022—however Holmes wasn’t there for it. He had, one yr earlier, taken the highest job in Detroit. The primary transfer he made was buying and selling the Lions’ all-time main passer, Matthew Stafford, to the Rams. The torment was poetic: Detroit’s new normal supervisor watched his mates have a good time a championship in his first yr faraway from his former franchise, whereas Lions followers watched their former quarterback hoist the Lombardi Trophy one yr after requesting a commerce from Detroit.

Holmes vowed to make use of that heartache. He informed himself that he would construct Detroit’s group round individuals who had suffered like him—individuals who knew methods to use that struggling as gas. He hoped to discover a accomplice who embraced the darkness like he did.

After which he met Dan Campbell.

When he was launched as Detroit’s new head coach, at a press convention in January 2021, Campbell went viral with a breathless speech promising bodily hurt to opponents. “This group’s going to be constructed on—we’re going to kick you within the enamel. All proper? And while you punch us again, we’re going to smile at you,” Campbell mentioned. “And while you knock us down, we’re gonna rise up. And on the way in which up, we’re gonna chew a kneecap off. All proper? And we’re gonna arise. After which it’s going to take two extra photographs to knock us down. All proper? And on the way in which up, we’re gonna take your different kneecap. After which we’re gonna rise up. After which it’s gonna take three photographs to get us down. And after we do, we’re gonna take one other hunk out of you.”

He concluded: “Earlier than lengthy, we’re gonna be the final ones standing.”

Campbell was rendered a caricature. All of the nationwide media may see was a macho former participant flexing for the cameras; all they may hear was the Texas twang and the grisly imagery. However Lions followers noticed and heard one thing else. We weren’t enamored of the kneecap spiel. What made us fall in love with Campbell—what turned him into the face of Detroit sports activities—was what he mentioned instantly previous that viral second.

“This place has been kicked, it’s been battered, it’s been bruised. And I can sit up right here and offer you coach-speak all day lengthy. I can provide you, ‘Hey, we’re going to win this many video games.’ None of that issues, and also you guys don’t wish to hear it anyway. You’ve had sufficient of that shit,” Campbell mentioned. “Right here’s what I do know: This group goes to tackle the id of this metropolis. This metropolis’s been down, and it’s discovered a solution to rise up.”

How does a man who grew up within the one-stoplight-town of Morgan, Texas (inhabitants 457)—“truly, outdoors Morgan,” Campbell informed me—turn into an avatar for the defiant spirit of Detroit?

Campbell performed right here. Extra to the purpose, he performed right here in 2008, when the Lions achieved infamy with their 0–16 season. He got here aboard as a free agent with the cost of offering veteran management, serving to a languid locker room to mature and compete. As a substitute, in his three years in Detroit the group misplaced 38 video games and gained simply 10. The 2008 season was particularly scarring. Campbell, who nursed accidents all through coaching camp, fought his manner onto the sector within the season opener in opposition to Atlanta. Within the second quarter, he caught a move for 21 yards down the seam, getting crunched by three Falcons defenders on his solution to the turf. Then he limped off the sector.

“That was my final play ever,” Campbell murmured.

We have been sitting on the sidelines of the Lions’ indoor observe subject. He closed his eyes, wanting wistful. The cumulative toll of accidents sustained enjoying the sport he cherished—foot, elbow, knee, hamstring—lastly caught up with him. He watched from the sidelines as his group misplaced each recreation that season. What occurred subsequent was simply as excruciating: Campbell signed a one-year cope with the New Orleans Saints, decided to provide his physique a ultimate go. He tore his MCL in camp and was positioned on injured reserve, forfeiting eligibility to play. This time, as an alternative of watching his teammates go winless, Campbell noticed the Saints march all the way in which to a Tremendous Bowl victory. However he didn’t get a hoop. He hadn’t performed a single down. Historical past wouldn’t keep in mind him as a champion. Campbell retired a short while later.

Detroit isn’t a prized vacation spot for soccer coaches. However for Campbell, who went to work for the Miami Dolphins as an offensive intern the yr after he retired, the Lions have been his dream job. This wasn’t only a place the place he performed. This was a spot the place he harm, the place he grieved, the place he misplaced one thing he would by no means get again—and the place the followers understood what that meant.

“Man, to endure yr after yr, your hopes are again up after which it’s that. Your hopes are again up—‘That is gonna be the yr’—after which it’s 0–16. However they simply maintain coming again for extra,” Campbell mentioned, shaking his head in amazement.

“The considered being part of bringing this place out of the ashes—”

He paused. “Man, it meant one thing to me.”

Campbell grew up a Dallas Cowboys fan. He watched each recreation along with his dad, a diehard because the Nineteen Sixties, and idolized the glamorous roster of the Nineties that gained a number of Tremendous Bowls. Now that he’s in Detroit, there’s a disconnect that’s laborious to disregard. These Cowboys had been dubbed “America’s Group,” but most of America couldn’t relate to them. They have been a gaggle of hotshot gamers, led by a cocky coach and bankrolled by an ostentatious proprietor, who gained in ways in which have been neither shocking nor inspiring. There was no grit concerning the Cowboys.

Jemele Hill: The Jerry Jones picture explains so much

“That’s been ‘America’s Group,’” Campbell informed me, emphasizing the nickname with air quotes. I may inform we have been considering the identical factor: Think about how endearing these Detroit Lions could be to the lots, soccer junkies and informal viewers alike, in the event that they parlayed their shedding previous right into a successful future.

Campbell motioned towards the sector behind us. “Why can’t we be America’s group?”

When the NFL scheduled the Lions-Chiefs season kickoff for September 7, my rapid response was to textual content the Mane Occasion crew. We started tickets, resorts, flights. Arrowhead Stadium, in prime time, in opposition to the champs—this was as near a Tremendous Bowl as something we’d ever skilled. We needed to go.

It hit me a number of hours later: September 7 was our marriage ceremony anniversary. Our tenth marriage ceremony anniversary. As a lot as my id is wrapped up in Lions soccer, it’s much more wrapped up in household. There was no manner I may ditch my spouse. So I did what any good husband would: I requested her to return to Kansas Metropolis, too.

She truly agreed, however between our jobs and children and logistics, we couldn’t discover a solution to make it work. She felt horrible about it. However I informed her to not fear: The Lions could be enjoying loads of large video games in 2023. We’d have loads of probabilities. In any case, we have now 4 season tickets.

I considered these 4 tickets all through the summer season. Buying them just a few years in the past after shifting again to Michigan had been a method of building continuity between generations, passing down a household custom, making certain that my three boys would make Lions recollections—good and dangerous—with their father the identical manner I had with mine.

That not appeared seemingly. I had stopped pushing the Lions on them final summer season, following that terrible preseason loss to Atlanta, and I hadn’t heard a phrase from them about soccer since. That was simply high-quality. My sons and I might uncover a unique id collectively, a unique manner of bonding. Certain, if I’m being trustworthy, it was a disappointment. However I’ve discovered to cope with these.

A couple of days earlier than I completed scripting this story—two weeks out from the season opener—my 7-year-old, Lewis, approached me, apropos of nothing.

“Dad,” he requested, “can we go to a Lions recreation this yr?”

I used to be reminded of one other advantage of shedding: It makes victory that a lot sweeter.

Related Posts

- Connection and Resilience within the Asian American Group

The Asian American neighborhood in Southeastern Pennsylvania is numerous. The Asian diaspora consists of folks…

- Wholesome Growing old within the LGBTQIA+ Group

There’s numerous proof that people who find themselves LGBTQIA+* are more likely to have sure…

- Ascot Group appoints new group CFO

Marck Wilcox will report back to group CEO and president Jonathan Zaffino. Credit score: Shutterstock.com.…