In the summer season of 2020, the playwright Michael R. Jackson acquired an uncommon message from a fan of A Unusual Loop, his musical a couple of homosexual Black man’s path to inventive self-awareness by means of the method of writing a musical a couple of homosexual Black man’s path to inventive self-awareness. “Can I purchase you a bulletproof vest?” the fan inquired over Instagram.

Jackson, who had simply received a Pulitzer Prize for A Unusual Loop and lived on a wonderfully secure avenue in Higher Manhattan, had no extra conceivable use for physique armor or handouts than the subsequent man. He instructed me concerning the proposal a number of months in the past, over steak frites at Soho Home, stressing its absurdity and presumptuousness. “Ur life issues a lot. Ur writing issues a lot. That is probably the most out there and direct method I can consider defending ur life and ur future performs,” the fan had defined.

In particular person, Jackson at first appears unassuming and even shy. He doesn’t reflexively generate small speak. However he responds candidly and at size when requested a query about nearly something, and he’s wickedly humorous. In Jackson’s analysis, the fan in query was haplessly impressed by the racial reckoning then gripping the nation; he felt compelled to “present up” within the identify of white allyship and anti-racism. Jackson compromised together with his would-be savior: For the good thing about the latter’s conscience, he’d settle for the vest’s money worth of $400. The person promptly despatched this sum to Jackson through Venmo.

This weird trade was emblematic of a complete constellation of assumptions, biases, and misunderstandings that has proliferated lately and altered the best way Jackson thinks of himself, his work, and American society extra broadly. “As soon as the pandemic and the protest started, I all of the sudden was like, Oh God. It is a check of all of our characters. That is the existential factor that none of us have really lived by means of earlier than,” he instructed me. He thinks the American elite failed that check, revealing the enormity of its disconnection from the true world.

Jackson can get animated when discussing the summer season of 2020 and the best way some artists, journalists, lecturers, and businesspeople exploited the killing of George Floyd to advance their profession. “They’re like, ‘Oh, on the earth the place George Floyd is useless, we have to speak about our theater careers’—or academia, or no matter … It’s like, how can y’all simply so casually use this man’s corpse to advertise your bougie-ass class bullshit? It’s disgusting.” He discovered media protection of this phenomenon to be notably oblivious. “The New York Occasions theater part will say”—right here he adopted a mock reporter’s voice—“ ‘Issues modified after George Floyd was killed, and this creative director was appointed to blah blah blah.’ ”

Jackson believes that social media, a gathering risk for a few years, tore open our collective actuality in 2020; it created “an alternate universe” during which identity-based struggling—or merely the declare to such, nonetheless implausible or vicarious—could possibly be transformed into social capital. “Within the theater world specifically,” he mentioned, “issues obtained instantaneously much more dramatic as a result of all of the sudden you had all these artists out of labor. And all they’d is the web to do probably the most Shakespearean of performances about George Floyd and every little thing else. The variety of folks within the theater world who used George Floyd’s useless physique to pivot to inequity within the theater world is probably the most hair-raising factor I’ve ever seen in my life.”

Many Black artists and thinkers, he mentioned, stay on this alternate universe: “They’ve made a house on-line the place they’ll unfold all of their affect and their clubbiness and cliquey-ness.” Right here, the delusion that the lives of Black artists are urgently endangered can tackle the false weight of standard knowledge—and encourage a blessedly naive white man to imagine {that a} Broadway author is someway in dire want of a bulletproof vest.

Jackson has lengthy been preoccupied by questions of race and sexuality. He is aware of that he advantages from the curiosity generated by two of his identities, Black and homosexual. He additionally believes that the superficiality of that curiosity—the oversimplification of complicated, ambiguous human actuality—can create a stifling mental lure. The playwright Jeremy O. Harris instructed The New York Occasions in March that “theater is an act of neighborhood service.” However Jackson is cautious of any social-justice consensus, which he believes encourages everybody “to take a look at artwork as a weapon for use to get one’s method.”

I started a sequence of conversations with Jackson within the autumn of 2022, as A Unusual Loop was winding down its Broadway run and he was getting ready to launch, off-Broadway, his extremely anticipated sophomore effort, an idiosyncratic satire referred to as White Lady in Hazard. He was additionally reaching past the theater world, writing for Boots Riley’s absurdist Amazon sequence, I’m a Virgo, which follows a 13-foot-tall Black teenager in Oakland, California. (It premiered in June 2023.) Now he’s writing a horror film—about, in his phrases, “the psychosis of an overeducated white and Black bourgeoisie”—for the manufacturing firm A24. He’s additionally engaged on a brand new play, referred to as Enamel, a couple of Christian teen in a spiritual neighborhood, which is able to open off-Broadway in March.

Jackson is often considered a member of the social-justice left in good standing—as “woke,” for lack of a greater phrase. But such a studying of Jackson and his work is a projection that claims much more about audiences and the vital local weather than the artist himself. I immersed myself in each of Jackson’s performs, in addition to his private writing in printed essays and on social media. And I grew to become satisfied that one among our period’s most shocking, ruthlessly self-aware, and incisive social observers simply occurs to put in writing musicals.

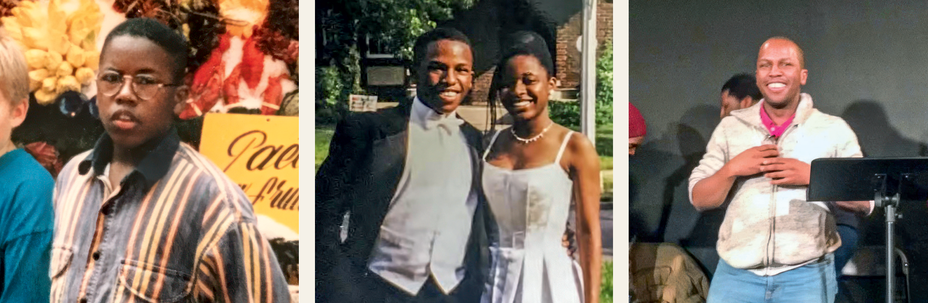

Michael R. Jackson was born in 1981 in Detroit, into what he has described as an unexceptional middle-class setting, a “Black Mayberry” the place “nobody appeared to need something and nothing of consequence ever appeared to occur.” His dad and mom—“regular-ass Child Boomers who’ve lived in the identical home for 45 years”—are each southern transplants, his mom from Georgia and his father from Mississippi. “Lots of people assume that being from Detroit means, like, ‘Oh, wow, you grew up at risk,’ ” he instructed me. “No, I grew up in a very regular, common neighborhood.” It was and nonetheless is a world of church outings and household reunions. A principally Black world the place “nobody is speaking about ‘I must be seen, I must be seen, I must be seen—look, Mommy, I can see myself!’ They by no means say that … Their shallowness isn’t managed by a digital world of digital managers and gatekeepers.”

If his household life was grounded and undramatic, his imaginative life was one thing like the alternative. When he was a really younger youngster, his working dad and mom would drop him off most days at his great-aunt’s home, the place he would watch hours upon hours of daytime tv: first cartoons, then sport exhibits, after which, beginning at lunchtime, cleaning soap operas. He recited the viewing order with relish: “12:30, The Younger and the Stressed ; 1 o’clock is Days of Our Lives ; 2 o’clock is One other World ; 3 o’clock is Santa Barbara.” As soon as he reached faculty age, Jackson would watch soaps on days off and over the summer season, calling his great-aunt to compensate for missed plot developments. “It was this bond that we had over these tales, these fictional white folks.” He mentioned these exhibits and these folks—“predominantly white ladies in peril”—taught him what the broader tradition deemed essential in storytelling.

At Cass Tech Excessive Faculty, Jackson studied inventive writing and devoured Cleaning soap Opera Digest in his free time, fantasizing about changing into a author on one among his favourite exhibits. The top of the English division inspired him to take part in a program that introduced skilled writers into the college, together with the novelist Peter Markus. Jackson studied privately with Markus. “He was the primary grownup in my life as an artist to problem me to push the envelope,” he instructed me. “His complete factor was ‘Work out what your obsessions are and write about them over and time and again.’ ”

Markus suggested Jackson to “cease imitating Maya Angelou” (Jackson’s phrases) and discover his personal perspective. Round this time, on the age of 15, Jackson started popping out as homosexual. And this rising twin sense of his inventive and sexual selves led him to need “to put in writing dangerously and to step out of what I felt, in an summary method, was this type of field of being a Black author who might solely write about sure issues and couldn’t be transgressive or emotional or no matter.”

Jackson has written frankly about his dad and mom’ shock at his homosexuality and their subsequent acceptance. As he put it in a 2021 essay for The Yale Overview:

My mom instructed me that God hated homosexuality and that being homosexual was worse than committing homicide. My father requested me if being drawn to males meant that I used to be drawn to him. Everybody cried. I felt like a cleaning soap opera villainess who had destroyed the household. Like I used to be Vivian Alamain burying Carly alive. And although my household and I are nearer than ever now, it took me a few years of tending to the wound to heal it, and even after therapeutic it there’s nonetheless a tiny scar.

For faculty, Jackson went to NYU, the place his love of cleaning soap operas endured, however he started to discover different dramatic types as effectively. He interned on All My Kids and took a playwriting class, the place his instructor outlined story for him: “A personality desires one thing, is offered with obstacles, and both achieves, fails, or abandons it.” When Jackson tried to put in writing from his personal perspective, nonetheless, the outcomes had been underwhelming.

His first full-length effort at NYU was a play referred to as DL, “a title and premise I stole from an episode of Oprah about Black males with secret ‘down low’ homosexual intercourse lives,” he wrote in The Yale Overview. “It was a couple of Black police lieutenant married to an outspoken southern born and raised accounting skilled who had a secretly homosexual teenage son. The son was having a sexual affair with one among his father’s white subordinates, who was additionally having a secret sexual affair with the daddy. The play was not good.” It possessed the uncooked substances of one thing doubtlessly highly effective—identification, trauma, deception—however Jackson nonetheless didn’t know what to make of them or how one can join his characters’ needs and obstructions to a extra compellingly common narrative. “As a younger artist,” he continues within the essay, “I used to be solely keen on exploiting an unresolved familial battle round my homosexuality and throwing it right into a pot with no matter dramatic seasoning I might discover within the cabinet.”

Jackson started work on what would grow to be A Unusual Loop after graduating from NYU, in 2002, when he was 21. After a brief internship at ABC Daytime, he utilized for an executive-assistant job at CBS Daytime however was turned down, so he went again to NYU for his M.F.A. in musical-theater writing. In grad faculty, he suffered a significant heartbreak that despatched him right into a despair. He had unfulfilling sexual encounters that he funneled into his writing challenge. After he completed his diploma, he saved writing. As his play—on the time titled Why I Can’t Get Work—expanded and developed, he staged just a few small performances. Generally folks walked out. Even because the play progressed, he admitted to me, it periodically additionally obtained worse. His skilled stagnation mingled with private setbacks that despatched him to remedy—a transfer he views as pivotal in stopping outright despair. All of the whereas, he had mind-numbing day jobs, together with as an usher at The Lion King and Mary Poppins. A lot of A Unusual Loop was born from that have, of “simply standing behind the theater watching folks watch the present.” A Unusual Loop was lastly produced off-Broadway in 2019 and opened on Broadway in 2022, when Jackson was 41. He had labored on it for twenty years.

A Unusual Loop is each the present the viewers has filed into their seats to observe and the play that its protagonist, Usher, an usher at The Lion King, is writing. Many of the motion happens in his overpopulated headspace, the place a supporting solid of Ideas, corresponding to Your Every day Self-Loathing and Fairweather (Usher’s projection of his agent), badger Usher to rush up and end writing. The supporting characters additionally reenact vital moments from Usher’s previous, together with botched sexual encounters and the day he got here out to his working-class dad and mom in Detroit.

The relentlessly polyphonic inside monologue makes for a frenetic, hilarious 100 minutes. In awarding Jackson its annual prize for drama in 2020, the Pulitzer board referred to as A Unusual Loop “a metafictional musical that tracks the inventive technique of an artist reworking problems with identification, race, and sexuality that when pushed him to the margins of the cultural mainstream right into a meditation on common human fears and insecurities.”

The play is rooted in its creator’s private experiences. But Jackson was additionally documenting his publicity to the bigger political local weather over time. Particularly, towards the top of the Obama administration, “these conversations began to bubble up within the tradition, and within the theater world notably, about this factor referred to as ‘range, fairness, and inclusion,’ ” which he had by no means actually thought of earlier than.

In 2015, Brett Ryback, a white actor and theater author whom Jackson had met at a writing residency, printed a weblog publish titled “Race and the New Era of Musical Theatre Writers.” In it, Ryback famous the shortage of range within the business. His critique was aimed on the present Pricey Evan Hansen, a success that had been written by two of Jackson’s associates. Ryback “was simply saying, ‘Why are the exhibits all white, and every little thing’s all white?’ After which he talked about me,” Jackson mentioned. The publish was extensively shared. “There are writers on this technology who’re taking us in a distinct path,” Ryback wrote. “Individuals like Lin-Manuel Miranda and Michael R. Jackson, who additionally occur to be writers of colour.” Jackson responded on his web site, his first try to make sense of a debate he has returned to repeatedly:

Whether or not you’re a white musical theater author or a musical theater author of colour, I might advocate for one thing that’s perhaps rather less politically right however undoubtedly on the facet of artwork when it comes to what makes it onto the stage:

JUST TELL THE FUCKING TRUTH.

That’s the one edict I might difficulty at this level. In case your solid is all white, is that the fucking fact? It might be! However you want to ask your self the query every time and never solely once you’re casting it but additionally as you’re writing it. Race is a assemble, so in that regard, it’s arbitrary, however racism is a follow—and one that’s typically unconscious or defacto. And it’s a follow that impacts all folks of colour in every single place. It’s a follow that impacts white folks as effectively and I might argue … that it might even have an effect on them worse.

In his response to Ryback, Jackson described his play-in-progress utilizing standard social-justice vernacular: “a bit that endeavors to pressure the hegemonic white gaze of the viewers to lie dormant and see issues as [Usher] sees issues as a black, homosexual man.” A Unusual Loop definitely accommodates traces of this progressive mindset, which, Jackson instructed me, “I not actually align with, however I saved in as a result of that’s the place the character is.” However greater than something, the play reveals “a altering thoughts, a thoughts that’s not static.”

Jackson cited one instance of his earlier mind-set, from a speech Usher delivers to his father during which he earnestly declares, “Black lust issues,” the implication being that Black folks ought to seek out their romantic completion in companions of the identical racial background. “I’m not there anymore,” Jackson instructed me flatly, noting that regardless that he would like to spend his life with a Black man, he has come to understand that “the homogeneity of thought” he typically finds inside his social class could make this a problem. “No person’s going to fuck you for those who don’t have an ideology they’ll agree with,” he mentioned. “Perhaps 5 years in the past, I rocked with this homogeneous thought. However I don’t anymore.”

A Unusual Loop additionally accommodates inside it the seeds of its personal subversion. Contemplate this line delivered by one among Usher’s interior voices within the guise of a guard in musical-theater jail: “Give them niggas a lil’ slavery, police violence, and intersectionality,” the voice advises the younger artist. Usher has a transparent lane to relevance and success ought to he content material himself with paint-by-numbers renditions of stereotypical Black life. However what can be the price? “To me, that line is a Rorschach check for folks,” Jackson instructed me. Is it skewering theatrical tastemakers, white audiences, or Black creators? Or all the above? “How they interpret that line tells me what their lens on the entire piece is.”

Eight years after the Obama period, Jackson says he has solely grown extra attuned to what he sees because the superficiality of the modern racial-justice discourse. “They aren’t actually saying what the implication of some of these things is,” he instructed me with exasperation, “as a result of there’s a darkish facet to it.” For one factor, he detects the presumption that “high quality is a white-supremacy construction, and that we might chuck it out the window in favor of conformity and of reallocating wealth.” Right here he was alluding to DEI supplies which have circulated extensively previously few years—such because the now-infamous anti-racist chart printed on the Nationwide Museum of African American Historical past and Tradition’s web site in the summertime of 2020. These newfangled tips sought to deconstruct “facets and assumptions of whiteness and white tradition.” Some problematic white traits included “rational considering,” “laborious work,” and “assembly your targets.”

Jackson confirmed me a exceptional mission assertion from the web site of a DEI advisor who’d been employed by the Lyceum Theatre, in Midtown Manhattan, a uncommon instance of claiming the quiet half very loud: “To dismantle systemic oppression and usher in a brand new period of empathy by producing participatory motion analysis, human useful resource initiatives and reallocating wealth to Black and Brown DEI consultants.” There may be not even a glancing point out of creative ambition or achievement.

Maybe much more ridiculous, in Jackson’s view, is how a deal with surface-level range, fairness, and inclusion can paradoxically stunt its beneficiaries artistically, even because it promotes their profession. He expresses gratitude for the sheer period of time he needed to write and excellent A Unusual Loop—an indispensable maturation course of that he thinks many gifted minority artists are being disadvantaged of in society’s haste to find and elevate nonwhite tales and voices. A play isn’t a weblog publish. Throughout these lengthy, lonely years that Jackson spent writing A Unusual Loop, he was capable of distance himself critically from his preliminary political views and transfer past a purely polemical mode. In contrast, the impact of the latest skilled fast-tracking, as he places it, has been to emphasise the flash of political positions over the drudgery of inventive improvement. “I’ve seen so many alternatives simply handed out, doled out to all these folks within the identify of giving them these sources, however there’s nothing being finished to assist them develop and to make a high quality product,” he mentioned.

Not each murals requires practically twenty years, however Jackson’s time funding in A Unusual Loop made the play what it’s: a wealthy palimpsest of viewpoints he’s recorded and effaced and written over once more, arguments he’s waged in opposition to himself in all his earlier iterations. This layeredness is likely one of the play’s nice achievements; the vertiginous lack of authorial certainty constitutes a core power.

But such layeredness will also be confounding to critics who now instinctively cut back artistic endeavors to political messaging. In a scathing overview of A Unusual Loop that ran in Nationwide Overview in April 2022, for instance, the author Deroy Murdock dismissed Jackson’s play as mere “vital race theater” and quipped that it “might have been composed by Robin DiAngelo (mom of White Fragility) with lyrics by Ibram X. Kendi (father of Be an Antiracist).” Murdock argued that “seemingly everybody Usher encounters bashes his race, sexuality, weight, and appears” and charged that Usher’s Manhattan is, subsequently, absurdly unrealistic. “Having lived on Manhattan Island since August 1987, I can attest that individuals right here don’t assault one another to their faces this fashion … That is 2022, not 1962.”

Such a studying will get issues precisely backwards. The dramatic battleground right here is not the white-supremacist, homophobic society into which Usher could also be thrust however his infinitely extra daunting and complex psychological terrain. His identification traits—chubby, Black, homosexual—are obstacles to his success largely as a result of he believes they’re. One among Jackson’s factors is that our experiences, nonetheless diverse they could be, in some very significant method quantity to what we make of them.

Conservative critics weren’t the one viewers led astray by the play’s racial cues. Within the autumn of 2022, I attended a sold-out efficiency of A Unusual Loop on the Lyceum Theatre. A number of seats to my left, an older white man positively squealed with delight at each utterance of “nigger.” The person cracked up even when there was no evident punch line on the horizon. I questioned if Jackson had ever had something like a Dave Chappelle second. Explaining his sudden departure from his legendary sketch sequence on Comedy Central, Chappelle famously recalled the abnormally lengthy, loud laughter of a single white spectator that had left him profoundly uncomfortable. “ My head nearly exploded, ” he instructed Time journal—he frightened he was really propping up the stereotypes he’d meant to critique.

Once I requested Jackson what he thought of this chance, his response was beneficiant and extra indifferent than I’d anticipated. “Once you purchase a ticket to one thing, you’re invited to have no matter expertise you need,” he replied. But when the white man’s conduct was weird and discomfiting, perhaps even racist, Jackson discovered different, extra frequent reactions anathema to the previous concept that artwork is for everybody. “There have been these Black individuals who would run as much as me and say, ‘That is for us. Thanks for telling our story. They don’t get it. They don’t get it. They didn’t know what they’re laughing at. They’re clapping alongside. They don’t know what they’re doing.’ They usually’d need me to know that they know what it’s.” He shook his head. “After which proper after that, a white particular person will come as much as me and go, ‘I know it’s not for me. I do know it’s not for me. I do know it’s not for me, however I cherished it.’ They need me to know that they know that it’s not for them. And I simply type of should calmly take all of that in, as a result of this goes to the center of the query: With all of this identity-marking and segregating and self-segregating and affinity teams and all these items, how have you learnt who’s it for? If I needed it to be for a bunch …” he trailed off. “When folks inform me that it’s for us, that’s this bizarre factor the place it looks like each Black particular person is similar.”

In dialog, Jackson repeatedly returns to the methods the evolving discourse round race, identification, and social justice fails to consider the views of flesh-and-blood Black folks. Jackson’s greatest good friend, Kisha, is a Black girl who runs a day-care heart in South Carolina. The 2 of them speak consistently about how initially compelling ideas like intersectionality have changed into rhetorical class markers. “So many of those [concepts] don’t have any sensible purposes to anyone’s precise lives,” he instructed me. “I wager you a garbageman has by no means needed to do a range coaching,” he mentioned. “This solely operates at a sure class stage.” Jackson mentioned his mom—one among eight youngsters, who left the Deep South, moved to the North, held down a job, raised a household, made a house—“would by no means name herself a feminist, not to mention an intersectional one.” But she is “probably the most highly effective Black ladies I do know.” The difficulty, as he sees it, boils right down to the truth that extra faculty is at all times required to make use of those phrases, and even to know them, and because of this they’re deeply exclusionary. “It’s a must to learn extra … It’s limitless working and studying and finding out,” he mentioned. “I really feel like there’s a rip-off within it that’s meant to maintain some folks on high and a few folks on backside.” He went on, “It’s all about these social-class associations, and also you both have entrance into this nation membership otherwise you don’t, based mostly on whether or not you subscribe to a sort of thought or perception system.”

Whereas nonetheless fine-tuning A Unusual Loop, Jackson was additionally plotting a brand new present, one that may abandon inward-looking theatrical autofiction in favor of a extra outward-looking critique. His second play, White Lady in Hazard, is ready within the realm of daytime tv, and marks an try to carry his cultural observations to the stage—“to placed on a canvas a type of image of a world that melodramatizes itself every day.” Jackson’s allegory is ingenious: The American racial drama has grow to be one big, insular cleaning soap opera.

One afternoon final March, I watched a rehearsal of White Lady in Hazard on the Tony Kiser Theater, in Midtown Manhattan. Jackson was sitting by himself, sharpening off a Shake Shack hamburger in a neon-pink T-shirt emblazoned with the faces of Viki and Niki from One Life to Stay. Not too long ago again to work after attending the Grammy Awards in Los Angeles (“They don’t feed you; there was no meals for 10 hours”) and The New York Occasions’ annual op-ed occasion (“Eric Adams is attractive”), he was surprisingly relaxed and easygoing, contemplating the expectations following A Unusual Loop, which, along with the Pulitzer, had received the Tony Award for Finest Musical.

His stage director, Lileana Blain-Cruz, swept into the room. She organized the solid and crew into an “vitality circle.” A sequence of deep-breathing workout routines shortly developed right into a dance-off as every member, together with Jackson, rapped and produced a novel motion for the handfuls of contributors to emulate. When the circle break up up, the musicians took their seats, and the solid broke into subgroups, getting ready to run by means of particular scenes within the second act of the three-hour manufacturing.

“If you’re white, please go away my area!” introduced the choreographer, Raja Feather Kelly, to a lot laughter. Brown-skinned members of the solid started marching in circles chanting, “Blackground issues!” whereas the pale-complexioned actors retreated into an imaginary city referred to as Allwhite and retorted, “Allwhites matter!” “You’re not Allwhite, you bitch! I’m Allwhite!” the actor Alyse Alan Louis screamed a number of instances, earlier than deciding on the correct enunciation.

“That is DEI theater!” Kelly shouted with a smile. Jackson requested me if I’d been following the latest Roald Dahl controversy, during which members of the British writer’s literary property determined to posthumously cleanse sure texts, eradicating phrases like fats and ugly. “I don’t imagine anybody really cares about these phrases,” Jackson mentioned. Individuals, he mentioned, are “simply exerting energy.”

The exertion of energy—over others, over oneself, to surmount obstacles and chart a novel future, to “select your individual journey,” so to talk—is a matter very a lot on the core of White Lady in Hazard. Within the soap-opera universe of Allwhite, a trio of white women, Meagan, Maegan, and Megan, are all threatened by a serial killer who stalks their suburban city, depositing our bodies within the surrounding woodland. In the meantime, the ladies take care of—amongst different afflictions—body-image points, terrible boyfriends, domineering moms, and, after all, white privilege. One typical line, which had stayed with me since Jackson had first sung it to me months earlier, goes, “She doin’ medication, however she received’t do her homework!” Whiteness, Jackson playfully suggests, can provoke the necessity to invent struggles that the world has in any other case failed to supply.

Their world is contrasted with the constricted second-class milieu of the nonwhite characters, most notably the spectacular mother-daughter duo of Nell and Keesha. The pair, because of an enigmatic and all-powerful Allwhite author—a sort of Oz determine throughout the play—are doomed to toil and dwell within the “Blackground.” Right here, identities are at all times contingent, ordered off a prix fixe menu: greatest associates, slaves, custodians, victims of police brutality. Jackson additionally suggests—because the keenest observers of American life by no means fail to do—that the white world is perhaps much more mass-produced and missing in originality by dint of its privilege. His white characters are stereotypes too; they only lack the self-awareness to do something about it.

The engine of the story, which is teeming with jokes and inside jokes, critiques and self-critiques, in addition to esoteric allusions, is Keesha’s need to transcend the confines of the Blackground by securing her personal autonomous plotline. When an Allwhite woman is killed by “the Allwhite killer,” the Allwhite author publicizes that the function of greatest good friend will henceforth be crammed by Keesha. However she is not content material because the sidekick. Keesha maneuvers to steal her Allwhite associates’ storylines, seducing their boyfriends within the course of. As she turns into extra profitable, racking up ever juicier subplots, her hair turns blond and the Allwhite author places her within the killer’s crosshairs. The revelation of the killer’s identification, in addition to that of the Allwhite author, comes as a shock. However the primary story right here is as previous because the Black expertise in America: what occurs when an bold particular person belongs to a marginalized group, but refuses the arbitrary limitations that include their identification. This play additionally suggests, extra coyly and controversially, that there will be actual energy within the sufferer posture. Keesha learns to govern her identification for private development, changing into a sort of predator who feasts on the Allwhite author’s indulgence.

White Lady in Hazard is much stranger and extra sui generis than I’d anticipated after I first started speaking with Jackson—and he’s much more severely keen on cleaning soap operas than I’d initially gathered. Watching all three hours of the musical felt bodily demanding to the purpose that, post-intermission, I questioned if the play’s kind mirrored its content material: American racial dynamics are actually exhausting. In fact Jackson is aware of this. He additionally is aware of that this present is much more weak to misinterpretation than his earlier one. “I feel there’s a method during which folks might have a look at the present and go, ‘That is an anti-woke musical,’ ” he instructed me. “However really, I consider it as a musical that may be a multiple-personality battle between woke and anti-woke. I’ve many targets, however I attempt, as a lot as I goal them, to even have compassion for them.”

Opposite to Kelly’s self-aware quip in rehearsal, White Lady in Hazard is decidedly not “DEI theater.” It’s definitely inclusive of Black actors, tales, and views. Nevertheless it doesn’t strictly adhere to or advance any explicit modern political place: The “Particular Thanks” a part of this system cites, amongst different influences, “PC/un-PC/woke/anti-woke” storylines. This attribute irreverence and anti-clubbishness is what makes Jackson such an incisive cultural commentator in addition to an uncompromising artist.

White Lady in Hazard’s off-Broadway run ended shortly, after solely 10 weeks. Audiences weighing in on social media tended to precise exasperation and bewilderment. Ordinarily, the subsequent objective for such a musical can be Broadway, however the present remains to be “very lengthy and really costly and obtained mixed-to-negative opinions—from the few I learn, which was admittedly only a few,” Jackson instructed me. “It’s potential it might have a regional life if I made some edits to make it a bit shorter and thus simpler and cheaper to supply, however that may necessitate an entire course of to develop that model that also had the integrity and imaginative and prescient I refuse to relinquish.” Vital adjustments have affected the theatrical panorama because the pandemic, most noticeably an absence of urge for food for creative danger on the whole, not to mention when the attitude on race is so unorthodox. “Being in the end a Black present that pushes distinctive boundaries in its message and nuance within the present sociopolitical local weather additionally challenges its financial viability,” Jackson instructed, whereas holding out the potential for creating White Lady in Hazard for movie or TV. Within the meantime, he has recorded an album with the solid.

On the night time I noticed White Lady in Hazard, Jackson appeared preoccupied with and probably nervous concerning the query of whether or not folks would get it. He could have genuinely been frightened about being canceled, which he’d joked about in rehearsal. However after I met him a number of weeks later at Soho Home, he was loquacious and relaxed, carrying a duplicate of Black Bourgeoisie, E. Franklin Frazier’s 1957 analytical work, whose paperback tagline reads: “The guide that introduced the shock of self-revelation to middle-class blacks in America.” Frazier’s thesis holds that the Black bourgeoisie is “a category seeking a mission,” alienated from the white mainstream along with lower-class Black actuality. “Chilly, laborious info!” Jackson mentioned, putting it on the desk. He isn’t completed making an attempt to carry a mirror to his personal second, and he isn’t completed laughing about it both, although the one element he would reveal with regards to his horror-movie script is that he finds it “terrifying.”

That night time at Soho Home, I discussed my love of the character Nell in White Lady in Hazard, who’s an amazing assortment of acquainted and shocking Black feminine roles performed to such impact by Tarra Conner Jones that she steals the present repeatedly. In an electronic mail, she instructed me that she was initially struck by “Michael’s audacity to be so daring and truthful about how black folks expertise, and are skilled in, a white world.” However in the end, she simply “laughed out loud quite a bit as a result of the script was humorous as hell.” Maybe probably the most good concept embedded in White Lady in Hazard is that the best way out of the crazy nationwide melodrama will essentially depend on humor. To this, Jackson replied that what he’s actually keen on now could be simply giving actors—and, by extension, audiences—the area to chuckle at themselves.

“Every part isn’t at all times concerning the legacy of slavery.”

This text seems within the March 2024 print version with the headline “The Radical Self-Consciousness of Michael R. Jackson.” Once you purchase a guide utilizing a hyperlink on this web page, we obtain a fee. Thanks for supporting The Atlantic.

#Michael #Jacksons #Subversive #Imaginative and prescient #American #Musical

https://www.theatlantic.com/journal/archive/2024/03/michael-r-jackson-criticism-playwright-musicals/677172/?utm_source=feed