Health Care

I Thought My Mom Was an Solely Little one. I Was Improper.

This story begins, of all issues, with a viral tweet. It’s the summer time of 2021. My husband wanders into the kitchen and asks whether or not I’ve seen the put up from the English theater director that has been whipping round Twitter, the one that includes {a photograph} of his nonverbal son. I’ve not. I head up the steps to my laptop. “How will I discover it?” I shout.

“You’ll discover it,” he tells me.

Discover the September 2023 Concern

Take a look at extra from this situation and discover your subsequent story to learn.

I do, inside a matter of seconds: an image of Joey Unwin, smiling gently for the digicam, his naked calves and sandaled toes just a few steps from an inlet by the ocean. Maybe you, too, have seen this picture? His father, Stephen, certainly didn’t intend it to change into the feeling it did—he wasn’t being political, wasn’t enjoying to the groundlings. “Joey is 25 immediately,” he wrote. “He’s by no means stated a phrase in his life, however has taught me a lot greater than I’ve ever taught him.”

That this earnest, heartfelt tweet has been appreciated some 80,000 occasions and retweeted greater than 2,600 is already placing. However much more so is the cascade of replies: scores of pictures from mother and father of non- and minimally verbal youngsters from everywhere in the world. A number of the children are younger and a few are outdated; some maintain pets and a few sit on swings; some grin broadly and a few have an effect on a extra critical, considerate air. One is proudly holding a tray of Yorkshire pudding he’s baked. One other is spooning his mother on a picnic blanket.

I spend practically an hour, simply scrolling. I’m solely partway by way of after I understand my husband hasn’t steered me towards this outpouring just because it’s an atypical Twitter second, suffused with the honest and the private. It’s as a result of he acknowledges that to me, the tweet and downrush of replies are private.

He is aware of that I’ve an aunt whom nobody speaks about and who herself barely speaks. She is, on the time of this tweet, 70 years outdated and dwelling in a gaggle house in upstate New York. I’ve met her simply as soon as. Earlier than this very second, in reality, I’ve forgotten she exists in any respect.

It’s extraordinary what we cover from ourselves—and much more extraordinary that we as soon as hid her, my mom’s sister, and so many like her from everybody. Listed below are all these photos of nonverbal youngsters, so pulsingly alive—their mother and father describing their pleasures, their passions, their strengths and types and tastes—whereas I do know nothing, completely nothing, of my aunt’s life in any respect. She is a thinning shadow, an growing older ghost.

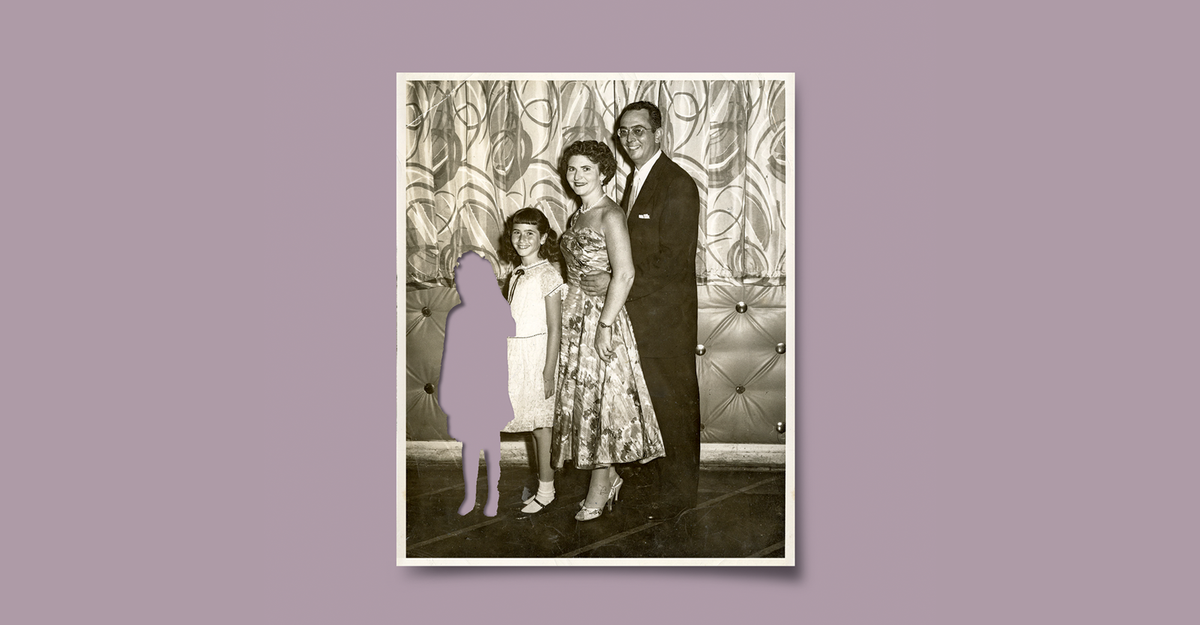

Once I first found that my mom had a youthful sister, I reacted as if I’d been instructed in regards to the existence of a brand new planet. This truth without delay astonished me and made an eerie form of sense, all of a sudden explaining the gravitational drive that had invisibly organized my household’s actions and behaviors for years. Now I understood why my grandfather spent so many hours in retirement as a volunteer on the Westchester Affiliation for Retarded Residents. Now I understood my grandmother’s annual journeys to the native division retailer to purchase Christmas presents, though we had been Jewish. (On the time, my aunt lived in a gaggle house the place the residents had been taken to church each Sunday.)

I now even understood, maybe, the sparkles of melancholy I’d see in my grandmother, an in any other case buoyant and intrepid persona, charming and sly and filled with wit.

And my mother: The place do you begin with my mother? For nearly two years, she had a sister. Then, on the age of 6 and a half, she watched as her solely sibling, virtually 5 years youthful, was spirited away. It might be 40 years earlier than she noticed her once more.

Unusual how seldom we take into consideration who our mother and father had been as folks earlier than we made their acquaintance—all of the dynamics and influences that formed them, the defining traumas and triumphs of their early lives. But how are we to know them, actually, if we don’t? And present them compassion and understanding as they age?

I used to be 12 after I realized. My mom and I had been sitting on the kitchen desk after I questioned aloud what I’d do if I ever had a disabled little one. This supplied her with a gap.

Her title is Adele.

She had crimson hair, I used to be instructed. Bizarre: Who in our household had crimson hair? (Really, my great-grandmother, however I knew her solely as a white-haired battle-ax devoted in equal measure to her cleaning soap operas and cigarettes.) She is profoundly retarded, my mom defined. There had been no language revolution again then. This was the correct descriptor, present in textbooks and medical doctors’ charts. My mom elaborated that the bones in Adele’s head had knitted collectively far too early when she was a child. So, a smaller mind. It was solely after I met her 16 years later that I understood the bodily implications of this: a markedly smaller head.

It was staggering to fulfill somebody who appeared identical to my mom, however with crimson hair and a a lot smaller head.

My grandmother instructed my mom that she immediately knew one thing was completely different when Adele was born. Her cry wasn’t like different infants’. She was inconsolable, needed to be carried in every single place. Her household physician stated nonsense, Adele was advantageous. For a whole yr, he maintained that she was advantageous, despite the fact that, on the age of 1, she couldn’t maintain a bottle and didn’t reply to the stimuli that different toddlers do. I can’t think about what this informal brush-off should have achieved to my grandmother, who knew, in some again cavern of her coronary heart, that her daughter was not the identical as different youngsters. Nevertheless it was 1952, the summer time that Adele turned 1. What male physician took a working-class girl and not using a school schooling critically in 1952?

Solely when my mom and her household went to the Catskills that very same summer time did a physician lastly provide a really completely different analysis. My grandmother had gone to see this native fellow not as a result of Adele was sick, however as a result of she was; Adele had merely come alongside. However no matter ailed my grandmother didn’t seize this man’s consideration. Her daughter did. He took one have a look at her and demanded to know whether or not my aunt was getting the care she required.

What did he imply?

“That little one is a microcephalic fool.”

My grandmother instructed this story to my mom, phrase for phrase, greater than 4 a long time later.

In March of 1953, my grandparents took Adele, all of 21 months, to Willowbrook State Faculty. It might be a few years earlier than I realized precisely what that title meant, years earlier than I realized what sort of gothic mansion of horrors it was. And my mom, who didn’t know the best way to clarify what on earth had occurred, started telling people who she was an solely little one.

It’s the fall of 2021. My aunt lives in a uniquely unlovely a part of upstate New York, a dreary grayscape of strip malls and Pizza Huts and liquor shops. However her group house is a snuggery of overstuffed furnishings, flowers, household images; the surface is framed by an precise white picket fence. It’s exactly the form of house you’d hope that your aunt, deserted to an establishment by way of a merciless accident of timing and gravely misplaced concepts, would discover herself in as she ages. When my mom and I arrive to see her, she is ready for us on the door.

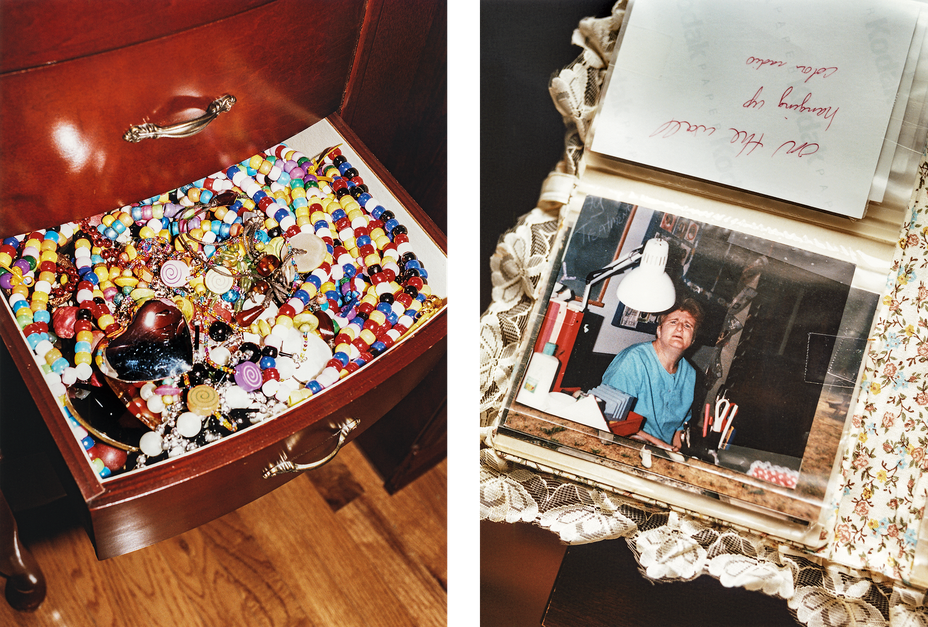

The drive to this home was 90 minutes from the place my people dwell in northern Westchester. But the automobile experience yielded simply 29 minutes and 15 seconds of recorded dialog with my mom. This might partly be defined by the unfamiliar instructions in her GPS, however nonetheless: Right here she was, visiting the sister she hadn’t seen since 1998—after which solely twice earlier than that, in 1993, shortly after her father died—and he or she had virtually nothing to say about the place we had been headed or what the climate was like inside her head. She appeared way more excited by telling me in regards to the necklaces she was making and promoting to help Hadassah, one in every of her favourite charities. Whether or not this was out of tension or enthusiasm, I didn’t know.

“Are you feeling nervous about seeing her?” I lastly requested.

“No.”

“Actually? Why not? I’m nervous.”

“Why are you nervous?”

“Why are you not nervous?”

“As a result of I made peace with my separation from her many, a few years in the past.”

My grandparents, for his or her half, had visited my aunt virtually each week, no less than when she was younger. Even after my grandmother moved to Florida, she made an effort to go to annually. Once I was in my late teenagers or early 20s, I bear in mind my mom telling me that Adele by no means knew or understood who my grandmother was, not ever. This truth caught with me—and hit me particularly arduous after I turned a mom myself. As we had been buzzing alongside the Taconic State Parkway, I reconfirmed: Adele didn’t acknowledge her personal mom?

“No,” she stated. “She didn’t know her. She didn’t perceive the idea of a mom.”

However when my mom final noticed her sister, in 1998, it wasn’t my grandmother who accompanied her. It was me. The entire journey had been at my instigation, identical to this one. I’d talked about that I used to be excited by assembly my aunt, and my mom had shocked me then, simply as she’d shocked me now, by saying, “Why don’t we go collectively?”

And what do I bear in mind of that singular day? How uncharacteristically animated and affectionate my mom was when she noticed Adele, for one factor. You might virtually discern the outlines of the little lady she’d been, the one who would circle Adele’s crib and play a made-up recreation she referred to as “Right here, Child.” Additionally, how petite my aunt was—4 foot 8, dumpling-shaped—and the way slack the musculature was round her jaw, which can have had one thing to do with the truth that my aunt had no tooth. She had supposedly taken a medicine that had made them decay, although there’s actually no solution to know.

However what stayed with me most from that day—what I considered for years afterward—had been the needlepoint canvases marching alongside the partitions in Adele’s bed room. My mom and I each gasped after we noticed them. My mom, too, was an avid needlepointer in these years, endeavor virtually comically formidable tasks—the Chagall home windows, the Unicorn Tapestries. Adele’s handiwork was easier, cruder, however there it was, betokening the identical ardour, the identical obsession.

One different factor: My mom and I found that day that Adele might carry a tune—and when she sang, she all of a sudden had lots of of phrases at her disposal, not simply sure and no, the one two phrases we heard her converse. Once more, we had been amazed. For years, my mom was a pianist and studied opera; her technical expertise had been impeccable, her sight-reading was impeccable, her ear was impeccable. She might decide up the phone and inform you that the dial tone was a significant third.

My mom couldn’t recover from it—the needlepoints, the singing.

I felt like I used to be gazing some form of photonegative of a twin research.

So right here we’re, 23 years later, and Adele is greeting us on the door. She is sporting a bright-red sweater. There’s my mom on the door. She, too, is sporting a bright-red sweater. Adele is sporting a protracted, chunky beaded necklace she has just lately made at her day program. And my mom, like her sister, is sporting a protracted, chunky beaded necklace she has just lately made—not at a day program, clearly, however for Hadassah. It seems that Adele loves making necklaces and has entire drawers of them. As, currently, does my mom.

I’ve an image of the 2 of them standing facet by facet that day. I can’t cease it.

Carmen Ayala, Adele’s extraordinary 79-year-old caretaker, has instructed Adele to say “Good day, Rona, I like you” to my mom, a gesture that’s each candy and awkward—Adele doesn’t know my mom by sight, a lot much less by title. Nonetheless, it catches my mom without warning, not least as a result of it means that her sister’s vocabulary has expanded significantly since we final noticed her, when she was dwelling in a unique group house. They embrace and take seats on the sofa in the lounge. We attempt, for a time, to ask Adele fundamental questions on her day, with out a lot success, although after we ask if she is aware of any Christmas carols—the vacation is arising—she sings “Santa Claus Is Coming to City” for us, and my mom replies in type with “Silent Evening.” Then Adele zones out, gazing her fingers. She will spend hours gazing her fingers.

My mom and I begin to ask Carmen and her youngest little one, Evelyn—she lives close by and is aware of nicely all three residents in her mother and father’ house—the customary questions: How did Carmen get into this line of labor? What’s Adele’s routine? How did Adele deal with the transition to Carmen’s home 22 years in the past, after her earlier caretaker retired? And though I’m within the solutions, I discover myself rising stressed, ideas of that Twitter thread plucking at my consciousness. I lastly blurt out: What’s my aunt like?

Evelyn replies first. “Very meticulous,” she says. “She wants issues a sure method, and she’s going to appropriate you the minute you do one thing flawed.”

I stare at my mom, who says nothing. I flip again to Evelyn and Carmen and immediate them. Equivalent to?

Her garments should match, they are saying, all the way down to the underwear. She retains her mattress pin-neat.

“She is aware of the place all the things is at,” Evelyn continues. “If we”—which means her or any of her relations—“come right here and we’re washing a dish and we put it within the flawed place, she’s going to inform us, Nope.”

I stare at my mom expectantly. Nonetheless nothing.

“Like, That doesn’t go there,” Evelyn explains.

At this level, my mom pipes up. “I don’t let anybody else load the dishwasher.”

Lastly.

“That’s Adele,” Evelyn says.

Arthur Miller’s youngest son, Daniel, was institutionalized. He was born with Down syndrome in 1966 and despatched to Southbury Coaching Faculty, in Connecticut, when he was about 4 years outdated. Miller by no means as soon as talked about him in his memoir Timebends, and Miller’s New York Occasions obituary stated not one phrase about him, naming three youngsters, somewhat than 4.

Erik Erikson, the storied developmental psychologist, additionally put his son with Down syndrome in an establishment. He and his spouse, Joan, instructed their different three youngsters that their brother died shortly after he was born in 1944. They ultimately instructed all three the reality, however not on the similar time. Their oldest son realized first. That should have been fairly a secret to maintain.

Pearl S. Buck, the Nobel Prize winner for literature and writer of The Good Earth, institutionalized her 9-year-old daughter, Carol, doubtless in 1929. However Buck was completely different: She recurrently visited her daughter, and 21 years later had the braveness to put in writing about her expertise in The Little one Who By no means Grew.

It’s outstanding what number of Individuals have relations who had been, sooner or later in the course of the previous century, sequestered from public view. They had been warehoused, disappeared, roughly shorn from the household tree. “Delineated” is how the Georgetown disability-studies scholar Jennifer Natalya Fink places it, which means denied their correct place of their ancestral lineage.

With time, we’d be taught the horrible toll that institutionalization took on these people. However they weren’t the one ones who paid a worth, Fink argues. So did their mother and father, their siblings, future generations. In hiding our disabled relations, she writes in her guide All Our Households, we as a tradition got here to view incapacity “as a person trauma to a singular household, somewhat than a standard, collective, and regular expertise of all households.”

That is exactly what occurred to Fink. When her daughter was recognized with autism at 2 and a half, Fink was devastated, regardless of her liberal politics and enlightened angle towards neurodiversity. Then she realized that the one disabled individual she knew about in her household was a relative who’d been institutionalized within the early ’70s. This despatched her on a journey to be taught extra about him—and in so doing, she found one more disabled member of the family, in Scotland. Had she identified way more about them—had they been an integral a part of household discussions and picture albums (and, within the case of the American relative, household occasions)—she would have had a far richer, extra expansive understanding of her ancestry; her personal little one’s incapacity would have appeared like “a part of the warp and woof of our lineage,” as she writes, somewhat than an exception.

From the October 2010 situation: Autism’s first little one

It occurred to me that this may increasingly have been one in every of my unconscious motives in attempting to get to know Adele at such a late stage of my very own life, along with easy curiosity a couple of misplaced relative. It might be a minor act of restitution, of relineation. With none malevolent intent, we’d all colluded in a single girl’s erasure. And our whole household had been the poorer for it.

Mass institutionalization wasn’t at all times the norm in america. Throughout the colonial period, folks with developmental and mental disabilities had been built-in into most communities; within the early 1800s, with the arrival of asylums and particular faculties, American educators hoped some might be cured and shortly returned to mainstream society.

However by the late nineteenth century, it turned clear that mental disabilities couldn’t be vanquished just by sending folks to the proper faculties or asylums, and as soon as the eugenics motion captured the general public’s creativeness, the destiny of the nation’s intellectually and developmentally disabled was sealed. “Undesirables” and “defectives” weren’t simply institutionalized; they turned the involuntary topics of medical experiments, waking from mysterious surgical procedures to find that they might not have youngsters.

Cue the road from Buck v. Bell, the notorious 1927 Supreme Courtroom case that upheld a Virginia statute allowing the sterilization of the so-called intellectually unfit: “Three generations of imbeciles are sufficient.”

Then the postwar period got here alongside, with its apron-clad moms and gray-flanneled fathers and all-around emphasis on a sure species of Americanness, a sure norm. “I’m talking in large generalities right here,” says Kim E. Nielsen, the writer of A Incapacity Historical past of america, “however I believe that push for social conformity exacerbated the unbelievable disgrace people had about relations with mental and bodily disabilities.” Institutionalizing such relations usually turned essentially the most enticing—or viable—choice. The stigma related to having a unique kind of little one was too nice; too usually, faculties wouldn’t have them, state-subsidized therapies weren’t obtainable to them, and church buildings wouldn’t come to their assist. “There have been no help buildings in any respect,” Nielsen instructed me. “It was virtually the other. There have been anti-support buildings.”

My aunt was born in that postwar interval. However I don’t assume my grandparents had been capitulating to social strain after they institutionalized Adele. They had been merely listening to the recommendation of their medical doctors, authoritative males with white coats and granite faces who instructed them there was no level in maintaining their daughter at house. In keeping with my mom, my grandparents ferried Adele from one specialist to a different, every declaring that she would by no means stroll, by no means speak, by no means outgrow her diapers.

Which raised a query, on additional reflection: Did my aunt’s situation have a reputation? As we had been driving alongside, my mom instructed me she didn’t know; Adele had by no means had genetic testing.

Actually? I requested. Even now? Within the 2020s?

Actually.

My grandparents are not with us. I do know little of what they had been instructed or how they felt after they had been suggested to ship their second little one away. However I think about the script sounded much like what a doctor instructed Pearl S. Buck when she took Carol to the Mayo Clinic. “This little one will likely be a burden on you all of your life,” he stated, in response to Buck’s memoir. “Don’t let her take up you. Discover a place the place she may be pleased and go away her there and dwell your individual life.” She did as she was instructed. Nevertheless it violated each ounce of her maternal instinct. “Maybe one of the best ways to place it,” she wrote, “is that I felt as if I had been bleeding inwardly and desperately.”

“The mother and father who institutionalized their youngsters—they too are survivors of institutionalization and victims of it,” Fink instructed me. “They had been damaged by this. It was not offered as a alternative, for essentially the most half. And even when it was, the medical institution made it look like institutionalization was the finest alternative.”

That utilized to my grandmother, a tower of resilience, a lady who survived her father’s suicide, a brutal knife assault by a madman in a public restroom, and breast most cancers at a comparatively younger age. She, like Buck, bled inwardly and desperately, in essentially the most literal sense, creating an ulcer when my mother was 11 or 12. “Earlier than Grandma died, she began speaking about Adele, and for the primary time that I can bear in mind, she admitted that she felt horrible institutionalizing her,” my mom instructed me as we drove. “Once I reminded her that if she had not institutionalized her, no one within the household would’ve had a standard life, she stated, ‘Sure, however she would’ve been with individuals who liked her.’ ”

One of many beneficiaries of that so-called regular life was, ostensibly, my mom. In his magisterial Far From the Tree, the author Andrew Solomon notes that essentially the most generally cited rationale for institutionalization in these years was that neurotypical siblings would undergo—from disgrace, from consideration hunger—if their disabled siblings had been stored at house.

Nevertheless it’s extra difficult than that, isn’t it? My mom has by no means in her life uttered a cross phrase about her mother and father’ choice, and he or she’s hardly the type to play the sufferer—she might have been skilled as an opera singer, however she’s the least divalike individual I do know. But after I requested her what it was like when Adele left the home, she reflexively confirmed Fink’s speculation: She suffered. “It was like I misplaced an arm or a leg,” she stated.

In his second memoir, Twin, the composer and pianist Allen Shawn writes in regards to the trauma of dropping his twin sister, Mary, to an establishment after they had been 8 years outdated. He describes her absence as “an unmourned dying,” which carefully matches my mom’s expertise; he writes, too, that when she was despatched away, it felt to him like a type of punishment, “an expulsion, an exile,” which my mom has additionally recounted in melancholy element.

However what most captured my consideration was Shawn’s evaluation of how his sister affected his persona. “From an early age,” he writes, “I intuited that there have been tensions surrounding Mary and instinctively took it upon myself to proceed to be the better little one and keep away from worrying my mother and father.”

That was my mom: the peerless good lady. Excessive-achieving, rule-abiding, perfection-seeking. She skipped a grade. Till junior excessive, she selected training piano over enjoying with pals. In highschool, she sang with the all-city refrain at Carnegie Corridor.

Did she ever insurgent? I requested her.

“Nah,” she stated. “I used to be a goody-goody.”

To at the present time, my mom is the nice lady. Buttoned-up, at all times affordable, at all times in management. When hotter tempers flare round her, she defaults to a cool 66 levels.

My mom was thrilled when her mother and father introduced her new child sister house. She remembers Adele scooching to completely different corners of her playpen to observe her as she ran in circles round it. She remembers sitting on the kitchen counter and watching my grandmother put together bottles. She remembers my grandmother asking her to go on tiptoe into my grandparents’ room to see if Adele was asleep in her crib or nonetheless fussing. When my grandmother and grandfather started their frantic circuit of New York Metropolis’s specialists, questioning what might be achieved to assist Adele, my mom had no clue that something was the matter. Why would she? She was 6 years outdated. She’d at all times needed a sibling and now she’d been gifted one. Adele was marvelous. Adele was good. Adele was her sister.

When my grandparents left to take Adele to Willowbrook in March of 1953, that they had no concept what to inform my mom, settling ultimately on the story that they had been taking her sister to “strolling college.” My mother thought little of it. However for weeks, months, years, she stored anticipating Adele to return. When is she coming again? she would recurrently ask. We don’t know, my grandparents would reply.

At 8, my mom in the future had a sudden meltdown—turned unstrung, hysterical—and demanded rather more loudly to know when Adele could be returning, stating that it was taking her an awfully very long time to learn to stroll. That was the primary time she noticed my grandmother cry.

I don’t know, she nonetheless answered.

That very same yr, my great-grandmother, just lately widowed, moved in with my grandparents. Extra particularly, she moved into my mom’s room, into the dual mattress that Adele was alleged to occupy. My mom was livid about having to maneuver her issues, livid that she was dropping her privateness, livid that her grandmother was shifting into Adele’s mattress. (Now she modified the query she recurrently requested her mother and father: The place will Adele sleep when she comes house? And they might at all times reply: We’ll determine it out when the time comes.) Adele by no means did come house, and my grandparents would by no means attempt to have one other little one to fill that mattress. My great-grandmother was there to remain.

My great-grandmother: Lord. She meant nicely, I suppose. However she had solely a grade-school schooling and all of the subtlety of a flyswatter. When my mom was 13, my great-grandmother instructed her that she needed to be ok for 2 youngsters, good sufficient for 2 youngsters. “She stored emphasizing that my mother and father had misplaced a toddler,” my mom stated. The strain was terrible.

By 13, after all, my mom had already found out that one thing was completely different about her sister—and that Adele was by no means coming house. She’d heard the neighborhood children whisper. One cruelly declared she’d heard Adele was in reform college. Consciously or unconsciously, my mom started dealing with the state of affairs in her personal method, volunteering in lecture rooms for teenagers with mental disabilities. Two appreciated her a lot that she began tutoring them privately.

But all through my mom’s childhood, my grandparents by no means as soon as invited her to come back with them to go to Adele. At first she was instructed no youngsters had been allowed; by the point her mother and father did ask her to hitch them, my mom, at that time an grownup with youngsters of her personal, stated no. She felt too uncooked, too tender about it. She didn’t need to unloose a present of historical hurts. My grandparents by no means raised it once more.

I requested if she ever sat round and simply considered Adele. “Oh, positive,” she instructed me. “I ponder what she would’ve been like if she weren’t disabled. I ponder what sort of relationship we’d’ve had. I wonder if I’d’ve had nieces and nephews. Whether or not she would’ve had a husband, whether or not she would’ve had a very good marriage, whether or not we’d’ve been shut, whether or not we’d’ve lived close to one another …”

And what ran by way of her thoughts, I requested, when she set eyes on Adele for the primary time in 40 years, again in 1993? “I obtained disadvantaged of getting an actual sibling,” she stated.

For weeks afterward, I believed lengthy and arduous about this specific remorse. As a result of my aunt was an actual sibling. However no one in every of my mom’s era was instructed to assume this manner. The disabled had been dramatically underestimated and subsequently criminally undercultivated: hidden in establishments, handled interchangeably, decanted of all humanity—spectral figures at finest, relegated to the margins of society and reminiscence. Even their closest relations had been skilled to neglect them. After my mom got here house from that go to, she scribbled six pages of impressions titled “I Have a Sister.” As if she had been lastly permitting it to register. To acknowledge this clandestine a part of herself.

It’s painful, virtually too painful, to consider how otherwise my mom might need felt—how completely different her life and my aunt’s might need been—if that they had been born immediately.

It’s June of 2022. I’ve simply requested Adele what number of photos are sitting in entrance of me. My mom is skeptical. I ask once more. “What number of photos? One …”

“One,” she repeats.

“Two …” I say.

“Two, three,” she finishes.

I look triumphantly at my mom.

My mom is now someplace between skeptical and delighted. She tries herself. “What number of fingers?” she asks, holding up her hand.

“5.”

There are 5.

“She understands,” I inform my mom.

“Effectively, both that or she memorized it.”

I present Adele two fingers and ask what number of.

“Two.”

There’s a cause my mom is stunned. Once we visited Adele in 1998, she barely spoke in any respect, a lot much less confirmed that she had a notional sense of amount. (She’s going to immediately present us that she will depend to 12 earlier than she begins skipping round.) She wasn’t agitated again then after we noticed her, not precisely. However she wasn’t relaxed. A transfixing report about Adele, despatched to my mom not that way back, means that one of many causes she could also be extra alert now—and possesses a bigger vocabulary—is as a result of she’s on a greater, much less sedating routine of medicines.

However there’s one more reason, I believe, for my mom’s skepticism. Her entire life, she’d been given to grasp that Adele’s situation was mounted—that her sister was consigned to a life with none deepening or development. As she put it to me throughout that first automobile experience: “There could be no cause for her to get any extra cognizant or any smarter.” That’s how everybody considered incapacity again in my mom’s day. It’s my very own era—and those following—that got here to see the mind as a miracle of plasticity, teachable and retrainable proper into outdated age.

But Adele exceeded the expectations of all of the specialists who gave dire predictions to my grandparents. She did be taught to speak. She did change into toilet-trained. Not solely can she stroll, however she dances a imply salsa, which she exhibits us now—and the place she will get her sense of rhythm, I don’t know, but it surely’s nice. (I personally dance like Elaine on Seinfeld.) Carmen and her husband, Juan, each from Puerto Rico, usually play Latin music, and Adele jumps proper in, with one hand on her stomach and the opposite excessive and outward-facing, as if on the shoulder of an imaginary companion, all whereas shaking her hips and waggling her rear. Juan, whom she calls “Daddy,” usually joins her.

I ask Carmen (whom she calls “Mommy”) whether or not Adele is aware of any Spanish, provided that she and Juan converse it round the home. She says sure.

“¡Mamá! ” Carmen calls to Adele.

“What?”

“¿Tú quieres a papi? ” Do you’re keen on Daddy?

“What?”

“¿Tú quieres mucho a papi? ” Do you’re keen on Daddy quite a bit?

Adele nods emphatically.

“How a lot?” Carmen asks, switching to English. “How a lot you’re keen on Daddy? Let me see how a lot.”

“4 {dollars}.”

“4 {dollars}!” Carmen exclaims. “Oh my God.” Juan cracks up.

This type of confusion can be typical of what we see in Adele all through this, our second go to to the Ayala house. The report despatched to my mom, which incorporates assessments of the establishments she’s inhabited and the day applications she’s attended all through her life, frequently notes that she has hassle greedy ideas—that she “can title varied objects, however change into[s] confused when lengthy sentences are used.” It provides that she “usually mumbles and is obscure. If she doesn’t perceive what’s being stated to her, she merely says, ‘Yeah.’ ”

And we do have a tough time understanding her, and he or she does say “Yeah” to quite a lot of our fundamental questions on her day, which may make attending to know her irritating. However not when she turns into animated about issues she likes. Summer season is approaching, for example, which suggests Adele will shortly be going to camp. She adores camp. I ask what she does there. “A recreation! And shade.” Coloring, she means.

Different issues Adele loves: Care Bears, stuffed animals, blingy baseball hats, purchasing at Walmart, sporting fragrance, getting ready Juan’s nightclothes, tucking in her roommate every night time.

Camp is the one time Carmen really will get a break from caring for Adele and her two housemates—“I don’t like to go away them with no one,” she explains to me—and even when she does exit, she typically doesn’t journey very far.

I stare at Carmen, now 80, and understand I already dwell in worry of the second when she gained’t be capable to take care of my aunt anymore. She has pulmonary hypertension and requires oxygen each night time, and generally in the course of the day. But she nonetheless cares for her three prices, whose photos populate her picture albums proper alongside these of her organic children and grandkids. (My favourite: Adele standing subsequent to a life-size Indignant Chicken.) Daily, she helps bathe them; makes their beds; outlets for them; manages their varied physician appointments; takes them on outings; and, with Juan, prepares their breakfast, lunch, and dinner. 5 out of seven days, this implies rising at 5 a.m. In my aunt’s particular case, it means doing her hair every morning simply the best way she likes, placing in her earrings, and pureeing her meals—Adele refuses to put on her dentures.

“Once I was elevating my children, you already know—it’s one thing that you just miss,” Carmen explains.

Adele’s transition to the Ayala house wasn’t straightforward. Change is difficult for her; she likes order. And when she arrived at Carmen’s home 23 years in the past, she had scabies, which—along with elevating questions on how nicely cared for she’d been in her earlier house—meant that Carmen needed to throw out all the things she owned: her beloved stuffed animals, her garments, her sheets. The adjustment turned that rather more traumatic; now my aunt really had nothing. She threw tantrums. She as soon as referred to as Carmen “the B-word” (as Carmen places it). Carmen phoned the house liaison. “And she or he says, ‘Carmen, straightforward. She’s an excellent girl.’ ”

I ask how she earned my aunt’s belief. “I used to sit down down along with her and, you already know, I used to speak to her quite a bit,” she says. “Speaking, speaking, speaking to her. I’m telling her, ‘Come right here, assist me with this’ or ‘Assist me with that.’ ”

Now, Carmen says, Adele can recite all of her grandchildren’s names and is aware of them by sight. She demonstrates, asking Adele to call everybody in her son Edgar’s household. “J.J., Lucas, Janet, Jessica …” Adele says. Neither of her housemates can do that. “It doesn’t matter how lengthy she hasn’t seen them,” Evelyn, Carmen’s daughter, later tells me. “She is aware of who they’re. She has a reminiscence that she’ll meet anyone and he or she’ll bear in mind their title. That’s her present.”

Her present? I’m incredulous after I hear this. I hold enthusiastic about what I’ve been instructed my entire grownup life: that Adele by no means even acknowledged her personal mom, no less than so far as my mother understood it. Was this some form of misapprehension? Possibly Adele had identified my grandmother? Or possibly she hadn’t, however solely as a result of she’d been so aggressively narcotized?

As Carmen is speaking with us, Adele gently rests her head on my mom’s shoulder and retains it there. My mom, ordinarily a coil of self-discipline and management (at all times appropriate, at all times the nice lady), appears so blissed out, so pleased. When our go to is over, she tells me that this was her favourite half, Adele burrowing into her—and that she’s already enthusiastic about when she will subsequent see her once more.

November 22, 1977: On treatment because of head banging behaviors … She stares off into area, fixates on her fingers, or hair and has the compulsion to scent folks’s hair (Wassaic State Faculty, Amenia, New York).

That is from the report despatched to my mom, the one containing assessments of Adele from the completely different establishments she’s lived in and day applications she’s been part of. I had a better have a look at it possibly per week or two after our second go to.

February 11, 1986: (Psychotropic) Meds initially prescribed for screaming, hitting others, hitting self, excessive irritability (case-worker report from a day-treatment program, Ulster County, New York). It’s famous that she is taking 150 milligrams every day of Mellaril, a first-generation antipsychotic.

October 1991: Outbursts appear like psychosis … yell[s] out statements similar to “Adele. Cease that!” or … “Depart me alone!” (abstract of a report from a day program, Kingston, New York).

Late 2006: Psychiatry suppliers now acknowledge that there’s psychosis current and Zyprexa is successfully treating this (abstract of assorted evaluations).

The report is eight pages lengthy. However you get the thought. The pricey girl who nestled into my mom’s shoulder, waved at us till our automobile pulled out of sight, and just lately wandered into Carmen’s room when she intuited that one thing was the matter (Carmen was unwell) additionally had an unremitting historical past, till not that way back, of violent outbursts, self-harm, and psychosis.

Far be it from me to quarrel with those that evaluated her, together with the esteemed males in white coats. However “psychosis” appeared, after I learn this report, like an incomplete story, carrying with it the stench of laziness and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest reductivism—This individual is tough; let’s sedate her.

John Donvan and Caren Zucker: What we realized from autism’s first little one

I might have been completely flawed. Primarily based on this report, Adele actually appeared, at occasions, to pose a hazard to herself and others. However I discovered it curious that nowhere on this doc did it say something a couple of habits that even my untrained eye detected instantly throughout our visits: My aunt does tons of innocent stimming, the repetitive motions continuously related to autism. (She is very keen on wiggling her fingers in entrance of her eyes.) In all of the years of observational information about her—no less than from what I noticed right here—there wasn’t a phrase about this, or the phrase autism itself. And autistic people, when annoyed or confronted with change or responding to extreme stimuli, can generally behave aggressively—or in ways in which might be misinterpret as psychotic.

And so, for that matter, can traumatized folks.

It’s December of 2022. A visiting nurse, Emane, whom Adele calls Batman, is swabbing Adele’s cheek. My aunt is being candy and obedient; Emane, tender but environment friendly. The pattern will go to a lab in Marshfield, Wisconsin, that may sequence Adele’s genes.

Wendy Chung, the Boston Youngsters’s Hospital geneticist with whom my mom and I are working, has warned us that there’s solely a one-in-three likelihood that Adele’s genetic take a look at will come again with a situation or syndrome that has an precise title. However Chung has instructed me, as have quite a lot of different consultants, that there’s no different solution to know for positive what Adele has. Dozens of issues could cause microcephaly.

“But when you will discover out precisely what she has,” Chung says, “then you will discover a household—”

“—with a toddler who has it now,” I say.

Precisely, she says. After which I can examine how youngsters with this syndrome fare immediately, versus how they fared within the Nineteen Fifties.

My mom, Adele’s medical proxy, needed to signal the varieties to do that genetic take a look at. My aunt was incapable of giving her personal consent. And it happens to me, as I sit right here watching her so docilely enable Emane to rake her cheek with a Q-tip, that Adele has by no means been capable of give her consent for something, good or dangerous, her entire life. Not for the drugs she has taken, which can or might not have helped her; not for mammograms, which, given our household historical past, are indisputably a good suggestion. Not for any of the issues that had been achieved to her whereas she was institutionalized till the age of 28; not for a visit to the mall to get ice cream.

She can’t consent to this profile, I all of a sudden understand with some alarm.

I spend fairly just a few weeks fretting about this. Solely after talking with Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, a famend bioethicist and incapacity scholar, do I perceive precisely why that is so. The very last thing I need to do is damage Adele. So not writing about her could be per this want, consistent with the benevolent spirit of the Hippocratic oath: I’d be doing no hurt. Whereas I’m attempting to do good, a a lot riskier proposition. “The issue with attempting to do good,” she tells me, “is you don’t know the way it’s going to come back out.”

“I don’t have a authorized proper to know something about my kinfolk who had been disappeared,” says Jennifer Natalya Fink, who confronted an identical moral predicament when she wrote All Our Households. “However I’ve a ethical proper. And it’s an ethical flawed, what was achieved to them. For us to not hold perpetuating these wrongs, we’ve got to combine data of our disabled forebears.”

There stays a faculty of thought that privileges the privateness of individuals with mental disabilities above all else, significantly in the case of one thing as delicate as divulging their medical historical past. And this argument could also be proper. I don’t know. However I in the end determine, within the weeks after that swab, that integrating Adele means saying her title, and that understanding Adele—and her wants, and her potential, and whether or not she’s been handled with the suitable care and dignity her entire life—means figuring out and naming no matter syndrome she has. To chorus from doing so would merely imply extra erasure. Worse: It might indicate that her situation is shameful, and there’s been greater than sufficient of that in my household.

To hell with disgrace.

I don’t know why that is, however I hold coming again to my mom’s deep need for order. I had at all times assumed, I suppose, that it was a response to early trauma—a pure response to helplessly watching her sister get shipped away. However then I frolicked with Adele and found that she shared the identical trait, as if it had been inscribed within the household genes.

I point out this in the future to Evelyn, Carmen’s daughter, on the telephone. She mulls it over. “However possibly it comes from the identical place in Adele,” she says. “She was taken from her mom. She’s been managed her entire life. You don’t know what she’s gone by way of, the place she’s been.”

I sit in chastened silence for a number of seconds. She is completely proper. In fact it might come from the identical place. Adele little doubt additionally skilled savage trauma in her life. It was simply much less legible, as a result of she had no clear solution to convey it. For all I do know, my aunt is a matryoshka doll of buried ache.

In January of 1972, Michael Wilkins met in a Staten Island diner with a younger tv journalist named Geraldo Rivera and discreetly handed him a key. It opened the doorways to Constructing No. 6 at Willowbrook State Faculty, from which Wilkins, a physician, had just lately been fired. He’d been encouraging the mother and father of the kids in that ward—and others, from the sound of it—to arrange for higher dwelling circumstances. The administration didn’t like that very a lot.

In February of that yr, Rivera’s half-hour exposé, “Willowbrook: The Final Nice Shame,” aired on WABC-TV. It was sickening. To at the present time, it stays one of the vital highly effective testaments to the horrors and ethical degeneracy of institutionalization. You may simply discover it on YouTube.

Rivera was in no way the primary to go to Willowbrook. Robert F. Kennedy had toured the place in 1965 and referred to as it “a snake pit.” However as a result of Rivera all of a sudden had entry to one of many ghastliest dorms on campus, he and his digicam crew might storm the premises unannounced. What he discovered—and what his viewers noticed—was the form of struggling one associates with early-Renaissance depictions of hell. The room was darkish and naked. The youngsters had been bare, wailing, and rocking on the ground. Some had been caked in their very own feces. “How can I inform you about the best way it smelled?” Rivera requested. “It smelled of filth, it smelled of illness, and it smelled of dying.” He went on to interview Wilkins, who made it clear that Willowbrook wasn’t a “college” in any respect. “Their life is simply hours and hours of countless nothing to do,” he stated of the sufferers, including that 100% of them contracted hepatitis inside the first six months of shifting in.

Really, medical doctors had been intentionally giving a few of these youngsters hepatitis. Even into the Nineteen Seventies, the intellectually disabled had been the themes of government-funded medical experiments.

remedy, at Willowbrook State Faculty, Staten Island, New York, January 1972 (Invoice Pierce / Life Image Assortment / Shutterstock)

“Trauma is extreme,” Wilkins instructed Rivera, “as a result of these sufferers are left collectively on a ward—70 retarded folks, principally unattended, combating for a small scrap of paper on the ground to play with, combating for the eye of the attendants.”

“Can the kids be skilled?” Rivera requested at one level.

“Sure,” the physician stated. “Each little one may be skilled. There’s no effort. We don’t know what these children are able to doing.”

This was the place my aunt spent the formative interval of her youth, from the time she was a toddler till she was 12 or 13 years outdated. Although she left eight years earlier than Rivera and his crew arrived, it’s arduous to think about that the circumstances had been any higher in her day. As Kim E. Nielsen writes in A Incapacity Historical past of america, World Battle II was devastating for these establishments, which had been hardly exemplary to start with. The younger males who labored there have been shipped off to warfare, and a lot of the different staff discovered better-paying jobs and superior circumstances in protection vegetation. These state services remained dreadfully poor-paying and understaffed from then on, their budgets perpetually in governors’ crosshairs.

“It was horrible,” Diana McCourt instructed me. She positioned her daughter, Nina, born with extreme autism, in Willowbrook in 1971. “She at all times smelled of urine. Every part smelled of urine. It’s prefer it was within the bricks and mortar.”

Diana and her husband, Malachy McCourt—the memoirist, actor, radio host, and well-known New York pub proprietor—quickly turned outspoken activists and obtained concerned in a class-action lawsuit in opposition to the establishment. “I can’t fairly inform you how a lot they didn’t need us to witness what was happening inside,” Malachy instructed me. When youngsters had been offered to their mother and father, they had been taken to the entranceway of their dorm after being rapidly dressed by attendants. “The garments had been by no means her garments,” Diana stated. “She was sporting no matter they might discover within the pile.”

However most chilling of all was an offhand remark Diana made in regards to the stories she acquired about her daughter. They had been obscure, she stated, or demonstrably unfaithful, or maddeningly pedestrian—that she’d simply gone to see the dentist, for example. “The dentist,” Diana stated, “was infamous for pulling folks’s tooth.”

Wait, I stated. Repeat that?

“As an alternative of dental care, they pulled the tooth out.”

Is that how my aunt misplaced her tooth?

Rivera famous in his particular that the wards contained no toothbrushes that he might see.

I’d prefer to assume that Adele’s life improved when she went to Wassaic State Faculty in 1964. However New York produced, at that second in time, nothing however hellholes. (Rivera additionally visited Letchworth Village in his documentary, an establishment so terrible that the McCourts steered away from it, choosing Willowbrook as a substitute.) Wassaic, too, had a popularity for being grim. Not less than one notice from the report despatched to my mom indicated that my aunt was very eager on leaving it. The date was January 18, 1980. Adele was by then 28 years outdated and had sufficient of a vocabulary to get her level throughout. “Garments and suitcase?” she requested one of many clinicians.

Even when my aunt lastly transferred to residential care, dwelling in non-public properties and attending native applications in upstate New York, her remedy, till the ’90s, appeared lower than preferrred. In March of 1980, my aunt attended a day facility in an outdated manufacturing facility that also had very loud electrical and pneumatic machines, and the consequence was disastrous—“agitated, violent outbursts.” She was continuously taken to the “Quiet Room,” quilted with precise padded partitions, the place the employees would bodily restrain her. This follow, the report notes, is not utilized in New York.

It took seven years and 9 months earlier than her workforce realized that the commercial cacophony was inflicting a great deal of the issue.

It’s mid-December 2022. Adele’s genetic take a look at has come again.

Her dysfunction does certainly have a reputation. Remarkably, it will not have had a reputation if we’d examined her simply 4 years in the past. However in 2020, a gaggle of 50-plus researchers introduced their discovery of Coffin-Siris syndrome 12, the “12” signifying a uncommon subtype inside an already uncommon dysfunction. On the time they made this discovery, they might establish simply 12 folks on the planet whose mental incapacity was attributable to a mutation on this specific gene. Since then, says Scott Barish, the lead writer of the paper saying the discovering, the quantity has climbed to someplace between 30 and 50. So now, with my aunt, it’s that quantity plus one.

I instantly be a part of a Fb group for folks with Coffin-Siris syndrome. I discover only some mother and father with youngsters who’ve the identical subtype as Adele. One couple lives in Moscow; one other, Italy. However as quickly as I put up one thing about my aunt, there’s a flurry of replies from moms and dads of children throughout the Coffin-Siris spectrum, most of them centered on the identical factor: Adele’s age. Seventy-one! How thrilling that somebody with Coffin-Siris syndrome might dwell that lengthy! They need to know all about her, and what sort of well being she is in. (Sturdy, I reply.)

As a result of Coffin-Siris syndrome, first described in 1970, may be attributable to mutations in any one in every of a wide range of genes, its manifestations range. As a rule, although, the dysfunction includes some degree of mental incapacity and developmental delays. Many individuals with Coffin-Siris syndrome even have “coarse facial options,” a phrase I’ve come to utterly detest; hassle with completely different organ techniques; and underdeveloped pinkie fingers or toes (which is how, earlier than genetic testing got here alongside, a specialist would possibly suspect a affected person had it). Some, although in no way all, have microcephaly.

So far as I do know, my aunt’s fingers and toes are all totally developed—Coffin-Siris syndrome 12 doesn’t appear to have an effect on pinkies as a lot—and he or she doesn’t seem to have any organ hassle. She does, nonetheless, have microcephaly, as did 4 of the 12 topics in the breakthrough paper about her particular subtype. However what actually stood out to me in that research—and I imply actually shone in a hue all its personal—was this: 5 of the dozen topics displayed autistic traits.

In reality, the sparse literature on this topic suggests {that a} substantial portion of individuals with Coffin-Siris syndrome, it doesn’t matter what genetic variant they’ve obtained, have a analysis of autism spectrum dysfunction as nicely.

Which is what I’ve suspected my aunt has had all alongside.

Figuring out what I now do, I’m that a lot keener to discover a household with a toddler who has Coffin-Siris syndrome 12 that will be prepared to welcome me into their house. I name Barish, the lead writer of the breakthrough paper, who heroically refers me to 2. However one all of a sudden turns into shy and the opposite lives in Eire. I begin making my method by way of the opposite 50 co–first authors, co–corresponding authors, and simply plain co-authors listed within the research. For a protracted whereas, I get nothing—seems I’m speaking to lab folks, principally—although I be taught quite a bit about protein complexes and gene expression.

Then I attain Isabelle Thiffault, a molecular geneticist at Youngsters’s Mercy Kansas Metropolis. By some extraordinary fluke, she has, in her database, 4 youngsters with my aunt’s subtype. Two have microcephaly. A type of two is a 7-year-old lady named Emma, who lives within the Kansas Metropolis space.

I name her mother, Grace Feist. Would she thoughts if I paid a go to? She wouldn’t.

Grace and her husband, Jerry, took Emma in at seven months outdated and adopted her at a yr and a half, figuring out she had important mental and developmental delays. They had been ready. That they had fallen in love.

In addition they had ample state assets at their disposal, closely backed and even free. Extra nonetheless: That they had a wealthy universe of help teams to attract from, a classy public college of their yard, and the good thing about a tradition that’s come a great distance towards appreciating neurodiversity.

They had been capable of actively select Emma. Whereas my grandparents—pressured by medical doctors, stamped by stigma, damaged by exhaustion and confusion and ache—felt like that they had no alternative however to present their daughter away.

“So that is the perfect factor, as a result of it can hold your hair good and neat, and it doesn’t have any tingles.”

Tingles? I ask. It’s late February of 2023. We’re sitting in Emma’s bed room in Lee’s Summit, Missouri, and he or she’s waving a brand new silk pillowcase at me.

“They’re like large stuff in your hair.” She gestures at her thick brown ponytail.

Tingles … oh, tangles!

She nods. “Guess what? Tangles will get in your hair. If Mommy’s brushing, I will likely be so mad.”

A number of ft from her is a mounted poster that claims For like Ever. As in: We’ve embraced this little lady for all times—for, like, ever. Grace obtained it at T.J. Maxx shortly after Emma’s adoption turned official.

Each time I hear Emma converse, I discover it arduous to imagine that she and my aunt have a mutation in the identical gene. She chatters merrily in full sentences, talks about her pals, and may specific how she feels, usually in methods which can be shocking or fairly poignant.

“Emma, are you an identical as different children or completely different?” Grace asks after we decide her up at college the subsequent day.

“Completely different.”

“Why?” she asks.

“As a result of I’m the one one doing coloring. Not the opposite children.”

“Do you want being completely different?” I ask her.

“No.”

“Why?” I ask.

“As a result of I need to be like different folks.”

However what I’m caught on is all of the ways in which Emma began out like my aunt. When Grace and Jerry (a really concerned father, simply shy round reporters) first took her in at seven months to foster her, “she simply lay there like a two-month-old child,” Grace says. “We thought she was blind.” She didn’t make eye contact; she couldn’t roll. However in Bismarck, North Dakota, the place Grace and Jerry had been dwelling on the time, Emma was entitled to all types of state-funded early intervention, as she is in Missouri. By 9 months outdated, she was sitting unsupported, because of hours spent in a particular tube swing to assist her develop her core muscular tissues.

Emma wasn’t as late to stroll as Adele, however she didn’t take her first wobbly step till 16 months, and since it was 2016, somewhat than the early Nineteen Fifties, bodily therapists once more intervened, having her toddle on uneven surfaces—pillows, cushions—to bolster muscle tone. She developed a smoother gait at about 2, but it surely took a pair extra years for her to have the stability and coordination to stroll usually, or to climb the steps with out assist.

And speech! An enormous shock. Emma could also be a bubbly ingenue, telling me all about indoor recess and her BFFs at college, however that’s hardly how she began. When she was 4 years outdated, she had solely 100 phrases in her vocabulary, and that’s a beneficiant estimate. “The best way it was described was: She’s not deaf, but it surely’s virtually the speech of somebody who can’t hear,” Grace says. However Emma was working with state-funded speech therapists on the time, they usually decided that she had auditory-processing dysfunction. When she obtained to her public college in Lee’s Summit—which supplies further speech and occupational remedy to those that want it, plus extra studying and math instruction—her vocabulary began to develop, slowly at first, after which in a rush. “I don’t know what it was,” Grace says.

Effectively. I’ve some concept. It was having a supportive college. It was having a number of hours per week of occupational, bodily, and speech remedy from the time Emma was an toddler. And it was Grace herself.

If you happen to’re going to have an mental incapacity, who you really need as your mom is Grace Feist. Thirty-three, perpetually in flip-flops, and brimming with opinions—she has the concentrated vitality of a honeybee—Grace has gone to distinctive lengths to are likely to Emma’s schooling and psychological well-being. She’s adorned the basement playroom in pastels and muted colours. (“With visual-processing dysfunction, which Emma has, it’s not as overwhelming,” Grace explains.) As soon as per week, she takes Emma to imaginative and prescient remedy; she picks Emma up at college early day-after-day to focus much more on her studying and math at house, with out distraction. Grace is the queen of resourcefulness in the case of all issues pedagogical.

“I had a developmental pediatrician inform me: ‘There is no such thing as a rock you haven’t appeared underneath. That is what you’ve got, and that’s okay,’ ” she says. “And he got here from the perfect of intentions. However let me inform you, there have been, like, 50 rocks I hadn’t appeared underneath.”

As Grace and Emma give me a tour of Emma’s in-home classroom, all I can assume is, My God, the trouble. It incorporates a bucket of no less than 80 fidget toys, lots of them easy home items repurposed for anxious fingers (silicone sink scrubbers, stitching bobbins). Emma sits on a purple wobble disk—it appears like a whoopee cushion the scale of a satellite tv for pc dish—to proceed creating her core muscular tissues. The partitions are lined with big flash playing cards from Secret Tales, a phonics-based studying program that makes intuitive sense and appears form of enjoyable, which is an efficient factor, as a result of virtually nothing demoralizes Emma greater than attempting to learn. She will barely do it, although she’s attempting.

“How does studying really feel?” Grace asks.

“Mad,” Emma says. She’s sporting a resplendent lavender shirt with daisies on it. “As a result of if Mommy say, ‘Learn this now,’ I’d be tremendous grumpy. As a result of they’ve arduous phrases.” She’s pointing to a rudimentary guide she’s been battling. “However some folks say, ‘That is straightforward!’ ”

“How does that make you’re feeling?” Grace asks.

“Mad. Unhappy.”

We transfer on to have a look at the cabinets on the wall. They’re stocked with tactile studying instruments: numbers fabricated from sandpaper. Montessori cubes exhibiting multiples of 10. Wax Wikki Stix to make letter shapes.

“If you happen to change the method to all the things being multisensory—you see it, you hear it, you style it, you contact it, you scent it—then you definately be taught it,” Grace says. “Since you’re utilizing all these neural pathways for a similar data. Then everybody can be taught.”

Maybe I shouldn’t be stunned by Grace’s tenacity. She was raised in Florida, close to Orlando, and had her first daughter, Chloe, at 16. She joined the Navy as a reservist in 2010 and labored for a time as a army police officer; then she labored safety in an oil area in North Dakota, the place she made nice cash and obtained to see the northern lights, so long as she was prepared to place up with temperatures 20 levels beneath zero. She met Jerry, then an data technologist, on the web site Loads of Fish. Right this moment, he’s an expert YouTuber, with an inspirational-Christian channel that has 2.6 million subscribers. On December 28, 2016, they adopted Emma. In 2018, Grace gave beginning to a different daughter, Anna.

“Having Anna was the perfect factor for Emma,” Grace says, “as a result of it actually taught her the best way to play—with different children, even with toys. That mimicking, that seeing what to do. As a result of if you would purchase Emma toys, she would simply line them up.”

Grace and Jerry have made monumental sacrifices on Emma’s behalf. The entire household has. They don’t journey, as a result of Emma wants construction and management. They seldom go to eating places, however after they do, they convey alongside her purple noise-canceling headphones—capturing earmuffs, bought at Walmart—in case the sound overwhelms her; she wants to go away the restaurant a number of occasions a meal in any occasion, simply to floor herself. “That’s how we dwell our life,” Grace says.

Their life was once much more tough. When she was youthful, Emma, like my aunt, was inclined towards self-harm. Once I first point out to Grace that Adele has no tooth—and that I worry they had been eliminated at Willowbrook or Wassaic—Grace cuts me off: “As a result of she would chew herself till she bled?”

Candy Jesus. I hadn’t even considered that.

“As a result of Emma did,” Grace says. “I’ve photos of it.”

She doesn’t present me these photos. However she does present me an image of 4-year-old Emma with a large green-and-purple Frankenstein bruise bulging from her brow. “She’d hit herself within the face,” Grace says. “She would bang her head on the ground, like, arduous.”

And why does she assume Emma did that? “She’s trapped on this thoughts the place she is aware of what she desires, she is aware of what she wants, however you don’t know, and he or she doesn’t know the best way to inform you,” Grace says. “Is she aggressive? Yeah. I’d be pissed too.”

I haven’t seen any aggression in Emma—simply loads of sass, a gal who desires to point out off her dance strikes and introduce me to her stuffies. However once more, this can be partially because of early-childhood interventions: Armies of occupational and speech therapists taught her the best way to be mild, demonstrating the best way to speak kindly to dolls, they usually inspired Grace to show Emma signal language, which she did, in order that Emma might higher specific her needs. As Emma obtained older, Grace learn tons of books about emotional self-regulation, educating her daughter to externalize her frustration. “We’d be in the midst of Walmart and he or she’d be stomping her ft,” Grace says. “However you already know what? She wasn’t punching herself within the head.”

Right this moment, Emma is flourishing. She might not but know her telephone quantity or tackle. She might not be capable to inform you the names of the months or all the times of the week. However she’s making nice strides, particularly now that she’s studying at house. Once I left her home in late February, she might depend to 12; 4 months later, she was including and subtracting. “Emma goes to thrive in her life,” Grace says. “Is she going to work at McDonald’s? Possibly. Is she gonna bag groceries? Possibly. However she’s gonna be okay.” Grace’s objective, she says, is to make it possible for Emma’s psychological well being at all times comes first. “I’ve by no means met anybody extra resilient or decided,” she provides.

As I put together to go away, Grace provides me two presents she’s bought for my aunt. They’re issues Emma likes: a lavender-scented unicorn Warmie (a stuffed animal you may safely warmth within the microwave) and Pinch Me remedy dough that smells like oranges. “Something scented is at all times actually calming for Emma,” she explains.

Then Emma fingers me an image she’s drawn of me and Adele. Grace asks if she remembers why she drew it. “Yeah!” Emma says. “As a result of she has a tough time going to highschool.”

“Such as you,” Grace says. Then: “You recognize what her aunt has?”

I assume she goes to say one thing about Coffin-Siris syndrome 12, however in a method that’s understandable to a toddler who has it too. However that isn’t the place Grace is headed. “She has a lady who loves her and takes care of her as a result of her mommy wasn’t capable of. Similar to you. Do you know that?”

Emma shakes her head.

I thank Grace and Emma for the presents and head out to my rental automobile. I final possibly 30 seconds earlier than dropping it.

Is it a good or real comparability, lining up my aunt and Emma facet by facet? Utilizing Emma’s life story to this point as some form of counterfactual historical past? To ask What if?

Sure and no, clearly.

There’s variability in all genetic issues, together with Coffin-Siris syndrome, even amongst these with mutations in the identical gene. The unique paper my aunt’s particular subtype discovered that 4 out of the 12 people had microcephaly, for instance, however one had macrocephaly; go determine. My aunt and Emma, although they each have subtype 12, clearly have completely different manifestations of it, a phenomenon one can observe simply from them: Emma is large for her age whereas my aunt is tiny; my aunt’s microcephaly is unignorable, as a result of her sutures—the versatile materials between a child’s cranium bones—closed prematurely, whereas Emma’s didn’t, making her microcephaly tougher to detect. Her physician says it could be simpler to see as she will get older, although.

“In case your aunt had had the therapies obtainable immediately, I think her life could be very completely different,” says Bonnie Sullivan, the medical geneticist at Youngsters’s Mercy Kansas Metropolis who treats Emma. We’re talking simply days after I return house. She has checked out each Adele’s and Emma’s particular gene mutations. “She might not have been as high-functioning as Emma, however she might have maximized her potential, and her high quality of life would’ve been quite a bit higher.”

It appears unimaginable to quarrel with this evaluation. The literature on incapacity is bursting with tales—heartening or miserable, relying in your viewpoint—in regards to the advances made by folks with mental disabilities as soon as they had been liberated from the medieval torments of their establishments. Research way back to the Sixties confirmed that youngsters with Down syndrome start to talk earlier and have greater IQs in the event that they’re stored in house settings somewhat than institutional ones. Judith Scott, warehoused with Down syndrome in 1950 on the age of seven, famously turned an artist as soon as her twin sister established herself as her authorized guardian 35 years later; her good-looking fiber-art sculptures at the moment are a part of the everlasting collections of the Museum of Trendy Artwork and the Centre Pompidou.

However maybe the best-known instance of what occurs to underloved, understimulated youngsters are the orphans from Nicolae Ceauşescu’s Romania, the place “little one gulags” warehoused some 170,000 children in appalling circumstances. These youngsters turned tragic, unwilling conscripts in an inadvertent mass experiment in institutional neglect. When, 11 years after Ceauşescu’s execution, American researchers lastly started to review 136 of them, placing half in foster settings and monitoring their growth, the findings had been bleak. Solely 18 % of these nonetheless in orphanages confirmed safe attachments by age 3 and a half, versus virtually 50 % of those that’d been transferred to household settings. By the point the youngsters nonetheless in orphanages had reached 16, greater than 60 % suffered from a psychiatric situation.

Which brings me again to my aunt’s repeated diagnoses, over time, of psychosis. Possibly the situation was inevitable; possibly my aunt would have been psychotic it doesn’t matter what form of life she’d led. However after I watched these grotesque spools of footage from Willowbrook, all I might assume was: Who wouldn’t be pushed mad by such a spot? After she left Willowbrook, Adele would abruptly shout “Cease hurting me!” for no obvious cause. Her care workforce assumed she was having hallucinations, a believable postulate. However isn’t it equally believable to theorize that she was reliving some unspeakable abuse from her previous? Or, because the Georgetown thinker and disability-studies professor Joel Michael Reynolds places it (talking my ideas aloud): “Why isn’t {that a} fully affordable response to PTSD?”

I’ll by no means know the way Adele’s life might have turned out if she’d been born in 2015, as Emma was. All I’ve is a plague of questions.

What if a process drive of occupational, speech, and bodily therapists had proven up at my grandparents’ house every week, educating Adele to stroll, speak, and gently play with dolls?

What if she had spent her childhood not rotting in her personal diapers or staring on the partitions, however participating in organized play, attending college, and basking within the firm of adults who liked her?

What if she’d had caretakers who inhaled guide after guide about emotional self-regulation and inspired her to stomp her ft in department shops, somewhat than hit herself within the head?

And what if—what if—Adele had had a sister to play with?

It’s potential that each one the interventions on the planet would have achieved nothing, or subsequent to it. Sullivan says she’s seen households recruit each conceivable skilled and pour their energies into each conceivable intervention, but with depressingly little to point out for it. “There are some people with such extreme manifestations of sure issues that aggressive interventions don’t appear to vary the end result very a lot,” she says. “And it kills me. I actually grieve that consequence. As a result of the mother and father try all the things.”

Equally, there are kids who wind up in residential care regardless of their mother and father’ finest and most valiant efforts, as a result of their threat of self-harm or of harming others stays too nice. Mother and father should not, nor ought to they be anticipated to be, saints.

However my thoughts retains looping again to that eight-page report my mom was despatched about Adele’s historical past. The notes from Willowbrook, what few there are, inform a narrative all their very own.

March 19, 1953: 21-month-old lady, fairly small for her age … capable of sit with out help, to mimic actions, and is reported to have the ability to say “mama.” Adele’s IQ is measured at 52.

February 1, 1960: Microcephalic little one of 8 ½ years with restricted speech and partial echolalia. She is disoriented, and her acquaintance with easy objects in her environment is somewhat poor even for her total psychological degree … Charge of growth has markedly slowed down because the final analysis 7 years in the past. The ensuing drop in IQ is appreciable. This time it’s measured at 27.

In her seven years of gazing these partitions and rocking bare on the ground and by no means as soon as, I assume, being proven a particle of affection aside from these transient visits from my grandparents, Adele’s IQ dropped by virtually half, startling even those that evaluated her. And sure, possibly this was destined to occur; possibly her smaller mind had much less noticeable penalties in a toddler than in an 8-year-old.

But when my aunt might increase her vocabulary just by going off a ineffective antipsychotic and onto Zyprexa—in center age!—think about what else she might need been able to over the course of her life, if solely she’d been given a half, 1 / 4, a hundredth of an opportunity.

It’s A sunny day in Could of this yr. I’m engaged on the again deck, nearing the top of scripting this story. My cellphone rings. It’s Evelyn, Carmen’s daughter. She apologizes for calling me on a Sunday, however one thing critical has occurred. Adele has collapsed; she’s within the hospital; it’s wanting dangerous. Can I please find my mother?

I go away messages in every single place and name Adele’s nurse, Emane, who I’ve been instructed is within the hospital along with her. Emane is upset. Nobody will inform her something. She’s been banished to the ready room. They really want my mom, my aunt’s medical proxy.

A couple of minutes later, my mom telephones them. A couple of minutes after that, my father conveys the information to me: Adele has died.

A coronary heart assault, apparently. Simply after breakfast.

I name Evelyn. She is crying. I stammer my method by way of this dialog, additionally crying, however primarily as a result of we barely obtained to know my aunt, as a result of this was alleged to be the start of one thing and never the top, as a result of I do know the grief I really feel under no circumstances matches Evelyn’s or Carmen’s or Juan’s. I’m fluttering with an ungainly combination of disgrace, remorse, unhappiness. “She was liked,” Evelyn retains saying, again and again.

I do know, I say. I simply want extra by us.

“You got here at precisely the proper time,” Evelyn assures me. “I actually imagine that.”

I grasp up. God, they’re so gracious, this household. “We don’t choose,” Evelyn instructed us the primary time we went as much as see Adele on the Ayalas’. She meant it.

I telephone my mom. She has lurched into administrative mode, planning the funeral. That is peak Mother, organizing issues, surmounting the powerful stuff by discovering footholds within the small particulars. I wait a bit and name Carmen, although with some trepidation. My mom says she was unhelmed—bawling—after they first spoke. Carmen, calmer however nonetheless sobbing all through our speak, tells me it’s true. “I broke down. I didn’t count on it to occur like that.”

We bury Adele three days later. It’s a beautiful afternoon, good actually, however the incongruities and dissonances of the hour are arduous to disregard. Right here we’re, having a Jewish funeral for a girl who was by no means uncovered to the Jewish custom her entire life, whereas these whose lives have been most brutally upended—those that have spent the previous 24 years loving and caring for Adele—are Catholics. My aunt will likely be buried subsequent to her mom, perpetually reunited, whereas the girl whom she referred to as “Mommy”—who simply 4 nights in the past rubbed Vicks VapoRub on her again and introduced her tea as a result of she had a cough—will return to a home with an empty twin mattress.

I’d prefer to assume that within the afterlife, my grandmother’s coronary heart will mend. That she’s going to by no means once more be instructed to ship Adele away, that God will say to her: It’s okay, she’s beautiful as she is; she’s my little one too.

Downside is, I’m not a lot of a believer. I want I used to be.