Health Care

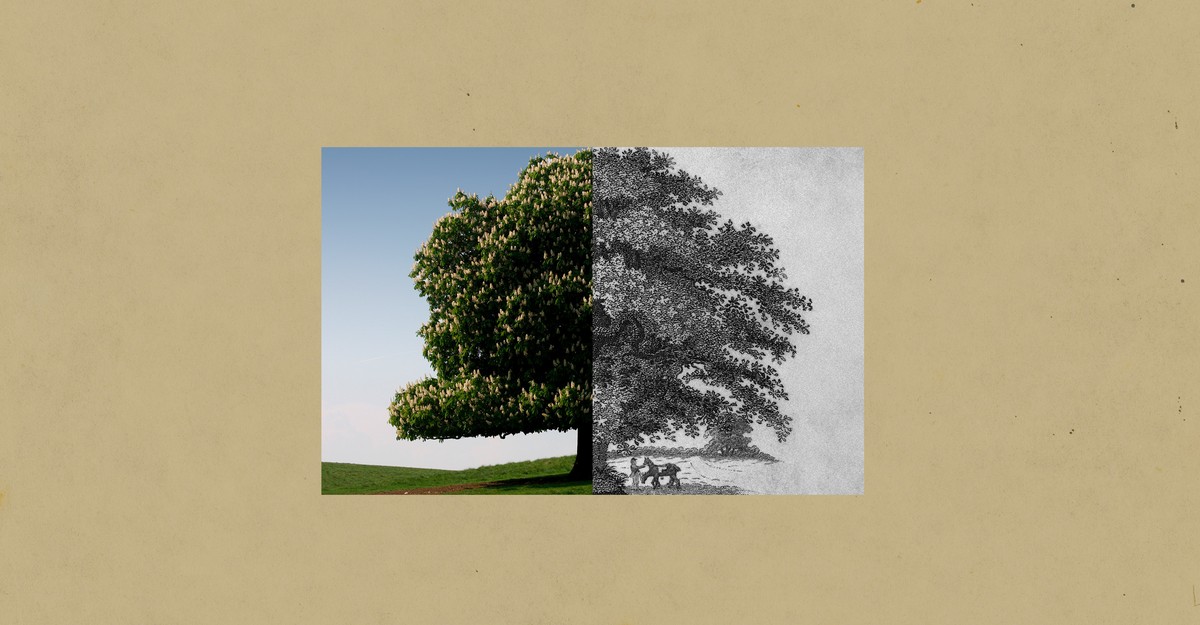

America Misplaced Its One Excellent Tree

Throughout the Northeast, forests are haunted by the ghosts of American giants. Somewhat greater than a century in the past, these woods brimmed with American chestnuts—stately Goliaths that would develop as excessive as 130 toes tall and greater than 10 toes broad. Nicknamed “the redwoods of the East,” some 4 billion American chestnuts dotted the USA’ japanese flank, stretching from the misty coasts of Maine down into the thick humidity of Appalachia.

The American chestnut was, as the author Susan Freinkel famous in her 2009 e book, “an ideal tree.” Its wooden housed birds and mammals; its leaves infused the soil with minerals; its flowers sated honeybees that might ferry pollen out to close by timber. Within the autumn, its branches would bend beneath the load of nubby grape-size nuts. After they dropped to the forest flooring, they’d nourish raccoons, bears, turkey, and deer. For generations, Indigenous folks feasted on the nuts, break up the wooden for kindling, and laced the leaves into their drugs. In a while, European settlers, too, launched the nuts into their recipes and orchards, and ultimately discovered to include the timber’ sturdy, rot-resistant wooden into fence posts, phone poles, and railroad ties. The chestnut turned a tree that would shepherd folks “from cradle to grave,” Patrícia Fernandes, the assistant director of the American Chestnut Analysis and Restoration Venture on the State College of New York Faculty of Environmental Science and Forestry, instructed me. It made up the cribs that new child infants have been positioned into; it shored up the coffins that our bodies have been laid to relaxation inside.

However in fashionable American life, chestnuts are virtually fully absent. Within the first half of the twentieth century, a fungal illness known as blight, inadvertently imported from Asia on commerce ships, worn out almost all the timber. Chestnut wooden disappeared from newly made furnishings; folks forgot the style of the fruits, save these imported from overseas. Subsistence farmers misplaced their total livelihoods. After reigning over forests for millennia, the species went functionally extinct—a loss {that a} biologist as soon as declared “the best ecological catastrophe in North America for the reason that Ice Age.”

The general public who lived through the American chestnut heyday are gone. However the nutty world they lived in might but make a comeback. For many years, a small cohort of volunteers and scientists—a lot of them the kids and grandchildren of chestnut growers lengthy gone—has been working to return the American chestnut to its native vary. It’s a quest that’s partly about salvaging biodiversity and partly a mea culpa. “The hope is that you could repair one thing that we as people broke,” says Kendra Collins, the American Chestnut Basis’s director of regional packages in New England. If restoration is profitable, it’ll convey again a tree not like some other—versatile, sensible, nourishing, uniquely American.

From the December 1874 problem: Previous timber

For all of its woes, the American chestnut isn’t technically uncommon: An estimated 430 million of the timber can nonetheless be discovered within the forests of the American East. However greater than 80 p.c of those timber by no means develop previous an inch or so in diameter, Sara Fitzsimmons, the American Chestnut Basis’s chief conservation officer, instructed me. Blight infiltrates cracks within the bark, basically girdling the stem till it starves; the roots under can survive to resprout however seldom stay lengthy sufficient to breed. Locked into an countless cycle of adolescence, loss of life, and rebirth, the plant can now not maintain the ecological features it as soon as did. When the tree went into decline, at the least just a few animal species that relied on it did too—amongst them, the American chestnut moth and the Allegheny woodrat, each of which, beneath further strain from deforestation and human encroachment, have been pushed to close extinction.

Reinstating the American chestnut’s former glory gained’t be simple. Blight is now entrenched in North America, unattainable to eradicate; the very best hope for the timber is to imbue them with pathogen tolerance. Many years in the past, that plan appeared easy: All American breeders would want to do, the pondering went, was cross the American species with their naturally extra blight-resistant Chinese language cousins just a few occasions over, making it attainable to tug off “the most important restoration in historical past” in as little as 20 years, says Brian Clark, the vp of orchard growth for the American Chestnut Basis’s Massachusetts/Rhode Island chapter. However in recent times, researchers have found that the blight resistance is scattered throughout “nearly each chromosome” within the Chinese language chestnut genome, Collins instructed me, making it tough to reliably breed the trait into mixed-lineage timber. Forty years into its tenure, the inspiration has efficiently bred a comparatively blight-resistant cultivar whose genome is roughly 5 p.c Chinese language. However the course of of manufacturing the timber is much more of a ache than researchers hoped.

Different chestnut lovers have as a substitute hung their hopes on a transgenic tree referred to as Darling 58, developed by a staff of scientists on the State College of New York Faculty of Environmental Science and Forestry. Its genome is fully American chestnut, save for a single gene, borrowed from wheat, that may assist the plant neutralize one of many blight’s most poisonous weapons. However with solely a single genetic defend in opposition to the fungus, “I believe blight will ultimately evolve round” the borrowed gene, says Yvonne Federowicz, the previous president of the American Chestnut Basis’s Massachusetts/Rhode Island chapter. The lineage’s resilience in opposition to blight has already been spotty—to the purpose that the American Chestnut Basis lately withdrew its help for Darling 58. (The ESF staff that designed the Darling timber, in the meantime, stands by them.) And a few Indigenous communities have expressed skepticism about introducing GMOs into the chestnut-restoration battle; in 2019, two members of the Basis’s MA/RI chapter—certainly one of them the chapter’s president—introduced their resignation in protest of the group’s help for transgenic timber.

No matter which American-chestnut strains stay in competition, Fitzsimmons instructed me, restoration might take centuries. Some 100 million acres of appropriate chestnut habitat, she stated, are ready to be crammed in the USA—no sole resolution will seemingly be sufficient by itself. However perhaps that’s becoming for a tree that refuses to relegate itself to a single function. “There are different timber that may produce greater crops in a given yr, or perhaps develop taller, or may be extra dense, or make extra beneficial lumber,” Andrew Newhouse, the director of ESF’s American Chestnut Analysis and Restoration Venture, instructed me. “However not all in the identical tree.” The American chestnut is, to our forests and our livelihoods, irreplaceable: “There aren’t actually any fashionable equivalents.”

Learn: The fading that means of ‘GMO’

Chestnuts of any selection are additionally completely scrumptious—phenomenal plain, roasted, and even uncooked, because of their sweet-savory taste and starchy texture paying homage to a baked candy potato. Japanese audio system usually describe them as hoku hoku—sizzling, fluffy, and flaky, a sensation that’s like a comfy balm on chilly, wintry days, Namiko Hirasawa Chen, the chef behind the meals weblog Simply One Cookbook, instructed me. In Europe and Asia, the place different species of the timber nonetheless thrive, days-long festivals have been devoted to consuming chestnuts. Right here, although, chestnuts are largely forgotten, save for in nostalgic Christmas songs.

However some folks bear in mind. Earlier this month, I drove to Central Massachusetts to attend the American Chestnut Basis’s MA/RI chapter’s annual assembly, the place board members and volunteers had ready a shocking potluck. Among the many tastiest dishes have been a creamy chestnut stew, a turkey-chestnut chili, and a cabbage-and-sausage dish studded with chestnuts. Better of all have been two desserts: flaky chestnut oat bars that melted like pie crust in my mouth and an expensive chestnut ice cream that made me neglect my lactose intolerance.

So far as I can inform, nobody appeared to have bothered cooking with American chestnuts; they’re the smallest of the varieties—some as teeny as chickpeas—and never environment friendly to work with. However on the shut of the assembly, an area grower, Mark Meehl, handed me a bag of Individuals from his Massachusetts orchards. The subsequent night, I scored them, parboiled them, and roasted them subsequent to some gargantuan Europeans, simply six occasions their dimension. It was, admittedly, a lot of labor. Nevertheless it made every nut treasured, virtually like a hard-won prize.

From the August 1897 problem: John Muir’s case for saving American forests

After I pried the Individuals open, I discovered them to be persistently sweeter, crunchier, and, nicely, nuttier than their European counterparts. And though a number of of the European chestnuts—imported from Italy—appeared to have rotted throughout their lengthy journey to my oven, each American nut was contemporary. Not a single certainly one of them had traveled greater than 50 miles from its supply. I scarfed all 10 of them down, and solely wished I might have strolled into the woods close to my home to assemble up some extra.

#America #Misplaced #Excellent #Tree

https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2023/12/american-chestnut-perfect-tree-restoration/676927/?utm_source=feed

Related Posts

- America Is Lastly Spilling Its Shipwreck Secrets and techniques

This text was initially printed in Hakai Journal.The Stellwagen Financial institution Nationwide Marine Sanctuary is…

- Abacus Life launches its market

Supply: Shutterstock Abacus Market is a part of the agency’s efforts to make life insurance…

- Born Primitive Launches Its First Efficiency Shoe With Its 'Savage 1'

Rising on-line health attire model; Born Primitive has put its greatest foot ahead by coming…